- Humanities

- 30 de April de 2024

- No Comment

- 6 minutes read

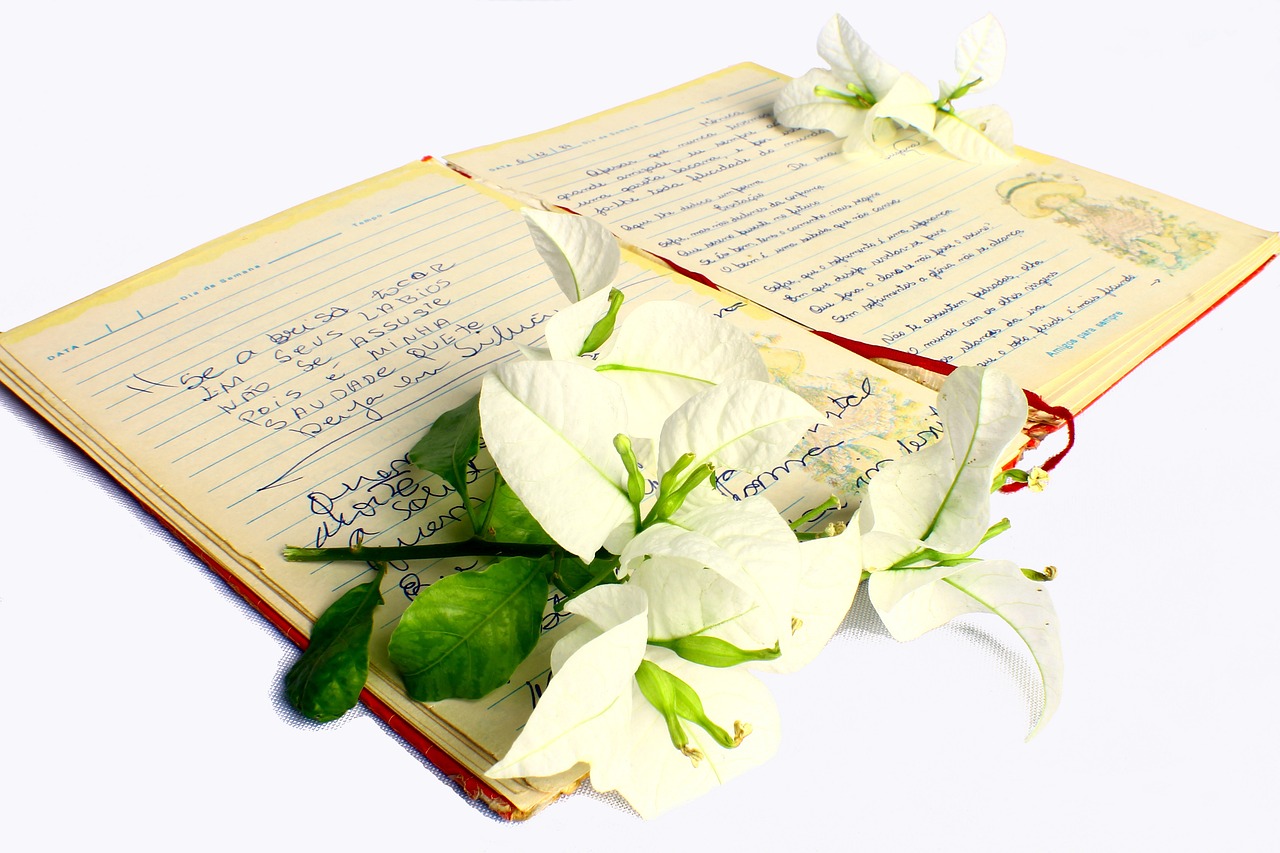

Poetry is, by far, the most useful of the arts

Poetry is, by far, the most useful of the arts

Poetry even serves to teach and learn sciences

The age-old refrain that poetry is useless — although I misspeak: it is not age-old; for millennia, until almost our time, people have not doubted that poetry was one of the most beneficial activities for the community. It reconnected us with nature, with the gods, and with ourselves — it has always seemed to me a “pamema” (DRAE1: affectation, pretence, futile or trivial act or saying). Contrary to popular belief, poetry serves many purposes. First and foremost, it prevents the poet from perishing, both literally and metaphorically. Some have sidestepped suicide or mitigated the effect of the bombs falling around them by crafting verses. And many others have avoided a living death through poetry: becoming resignees of existence, zombies who attend to daily obligations but who have lost the joy of laughter and the pleasure of breathing. For some, poetry offers a lesser but sufficient salvation: those who engage in it for the sheer joy it brings. This salvific and even redemptive pastime should not be dismissed: finding a meaningful activity to distract from the panic until Death arrives is no trivial matter or, as our unforgettable Mariano would say, it is a significant one. But, beyond the therapeutic effects that the infinite task of stringing words together to find alternative meanings to reality and our existence may have on some individuals, poetry possesses universal utilities, even more, it possesses pedagogical virtues: it teaches things, which will equip us to confront the challenges of an unavoidably hostile existence.

For example, poetry serves us to verify that language fights for justice and harms the powerful, as demonstrated in “The Stalin Epigram”, by the Russian Osip Mandelstam: “(…) the ten thick worms his fingers, /his words like measures of weight, / the huge laughing cockroaches on his top lip, / the glitter of his boot-rims. / Ringed with a scum of chicken-necked bosses / he toys with the tributes of half-men. / One whistles, another meows, a third snivels. / He pokes out his finger and he alone goes boom. / He forges decrees in a line like horseshoes, / One for the groin, one the forehead, temple, eye. / He rolls the executions on his tongue like berries. / He wishes he could hug them like big friends from home”. (translated by W.S. Merwin and Clarence Brown). Of course, it can also serve for the satirized tyrant to revolt and send you to the gulag, as experienced by Mandelstam. But this only proves the strength that poetry treasures and the violence with which it can inflict harm on malevolent forces.

Poetry also functions as a unique medium to articulate what cannot be expressed otherwise, often circumventing social censorship or the limitations imposed by reality. Take for instance Federico García Lorca, who was tragically executed by the Falangists for being a republican, a gentleman, and a homosexual (the latter of which led to him being shot twice in the buttocks when he was already dead) wrote shortly before he was murdered the wonderful Sonnets of Dark Love, a collection that remained unknown until 1986. Through these verses, he conveyed the love and desire he felt for another man (or men), sentiments he could not openly express in his life or his other literary works: “(…) Morning join us on the bed, / our mouths placed over the frozen jet / of a blood, without end, that was shed. // And the sun shone through the closed balcony, / and the coral of life opened its branch, / over my shrouded heart,” writes in his sonnet “Night of insomniac love”. (translated into English by A. S. Kline)

Poetry even serves to teach and learn sciences. Quevedo composed a poem to gold; Juan Ramón Jiménez, to a drop of nitric acid; César Vallejo, to phosphorescence; Gabino-Alejandro Carriedo, to the theory of iron; Clara Janés, to amethyst; Rafael Pérez Estrada, to aquamarine; Aníbal Núñez, to quartz; Lucretius, to the nature of things; Neruda, to the atom; Ángel Guache, to the law of gravity; Vicente Huidobro, to space-time (Juan Ramón also has two fundamental prose poems titled “Time and Space”); Joaquín María Bartrina, to electricity; Aurora Luque, to the speed of light; William Ospina, a prayer of Albert Einstein; Vicente Luis Mora, a mathematical sonnet; Enrique Morón, odes to numbers; and Ada Salas, a poem to the circle: “Exactitud del círculo. / Perfecta equidistancia / en torno a un centro. / Aguja del compás que se desliza / y traza // la forma inexorable de la espera”.

Poetry serves, in the end, as Oscar Wilde said, ‘to be beautiful’, and perhaps that is its greatest utility.

___

1 Diccionario de la Real Academia Española

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons