- History

- 4 de June de 2025

- No Comment

- 11 minutes read

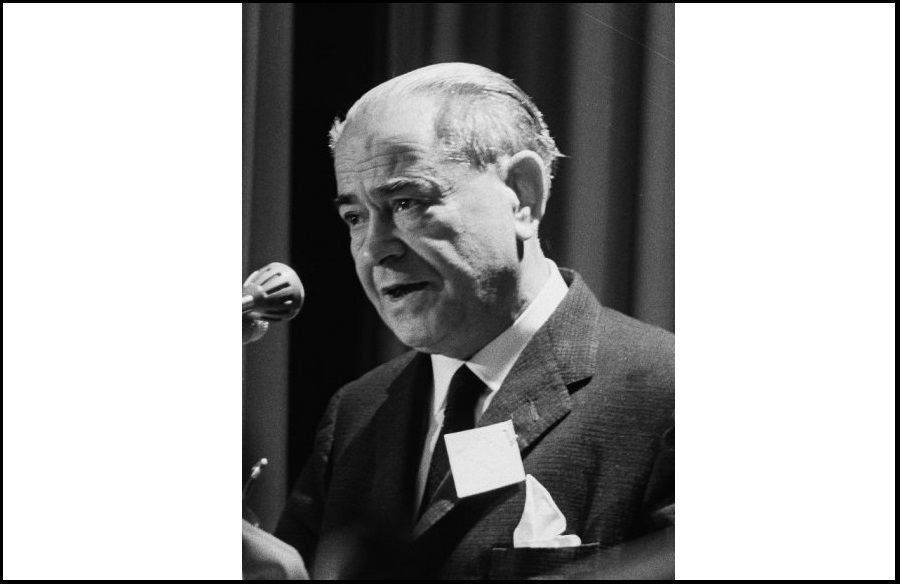

In remembrance of Rodolfo Llopis: A 20th-century educator and politician

In remembrance of Rodolfo Llopis: A 20th-century educator and politician

Soledad Bengoechea

At a time when Spanish society is once again immersed in a lively and perennial debate over the principles and structure of its education system, it is worth recalling the figure of Rodolfo Llopis Ferrándiz—educator, socialist leader and Freemason. One of the most influential figures in the history of Spanish education, particularly during the Second Republic, Llopis may now be viewed with calm, objectivity and scholarly rigour—free from ideological distortions, for neither he nor what he stood for poses a threat to anyone today.

Llopis was born on a cold 27 February 1895 in the town of Callosa d’en Sarrià, in the province of Alicante. Three years later, his family settled in the city of Alicante, where he would remain until completing his teacher training at the local Escuela Normal.

In 1911, his father’s posting as a sergeant in the Civil Guard brought the family to Madrid. There, Llopis was fortunate to encounter figures associated with the prestigious Institución Libre de Enseñanza. The following year, he took up a position as a Spanish language assistant at the Escuela Normal in Auch, France. He later enrolled in the Higher School of Teaching in Madrid, in the Humanities section, where he came into contact with prominent educators such as Manuel Bartolomé Cossío and Luis de Zulueta. In 1917, he joined the General Union of Workers (UGT), and was soon entrusted with the task of revitalising the association and turning it into a trade union aligned with socialist ideals. The organisation was subsequently renamed the Federation of Education Workers (FETE), which Llopis founded and presided over. Two years later, having completed his studies, he was appointed Secretary General of the (General Association of Teachers), originally established in 1912.

He was soon posted to the Escuela Normal in Cuenca, where he would lecture in Geography from 1919 until November 1930. At just twenty-six, he was already secretary of the institution and was actively engaged in renewing the pedagogical model, placing particular emphasis on hands-on activities such as local fieldwork and excursions to cities like Toledo, Madrid, Guadalajara, Alcalá de Henares and El Escorial—experiences previously unknown at the Escuela Normal in Cuenca.

It was at this time that he became gradually involved in Freemasonry. From 1923 onwards, he regularly travelled to Madrid to attend meetings of Logia Ibérica No. 7, of the Gran Oriente Español. There, alongside fellow republicans connected with La Lucha, a newspaper defending workers’ interests, he took part in the removal of two nuns from a convent, where they were being detained by ecclesiastical authorities. This act of “liberation” echoed the plot of Galdós’s Electra—a name which Llopis later gave to the Masonic triangle he founded in Cuenca. Under his leadership, Freemasons in Cuenca launched the newspaper Electra on 11 February 1930. Thirty-six issues were published, with contributions from teachers and lecturers such as Juan Giménez de Aguilar and Llopis himself. His Masonic activity declined during the Republic, when he became Director General of Primary Education, though he would later re-establish links with French lodges during his exile—albeit with less intensity than before.

In 1925, a new opportunity arose when the Junta para la Ampliación de Estudios awarded him a scholarship. This allowed him to travel for a year through France, Belgium and Switzerland to study “the organisational systems of teacher training colleges and the modern conception of geography, from content to strictly methodological concerns”. He attended lectures by leading geographers: Brunhes at the Collège de France; De Martonne, Gallois and Demangeon at the Institute of Geography in Paris; Blanchard at the Alpine Institute in Grenoble; Burky and Chaix at the University of Geneva; Hegencheid in Brussels; and Michotte at the Geography Seminar in Louvain.

Between 1927 and 1929, while continuing to teach at the Escuela Normal in Cuenca, Llopis began to take on responsibilities within national politics and the public administration. This gave him the chance to apply his pedagogical experience and to test the methodological principles he had embraced as a follower of the Institución Libre de Enseñanza—particularly the emphasis on nature, learning in open air, and valuing cultural heritage. He encouraged students to love and understand the land they lived in. For several years, he directed the monthly journal Escuelas Normales (1923–1936).

In 1928, he was able to travel to Soviet Russia. In Moscow, he took part in the Pan-Russian Congress of Education Workers and, on his return, published Cómo se forja un pueblo: la Rusia que yo he visto (How a People is Forged: The Russia I Have Seen).

Always a restless spirit, Llopis remained committed to keeping pace with the latest pedagogical ideas, in line with the ideals of the Institución Libre. He championed the model of the Escuela Única—later reformulated as a “Escuela Humana”—drawing on the most progressive international movements: Decroly, Dottrens, Ferrière, Claparède and Kerschensteiner. He was also deeply familiar with the work of Angelo Patri, to whom he dedicated his first book, La escuela del porvenir, según Angelo Patri (The School of the Future, According to Angelo Patri).

Undoubtedly, his most significant contribution as a political educator came with his appointment as Director General of Primary Education under the Second Republic, proclaimed on 14 April 1931. One of the Republic’s stated priorities was to saturate the country with schools. It is therefore unsurprising that three leading figures in education—Marcelino Domingo, Domingo Barnés and Rodolfo Llopis—assumed the key roles in shaping its educational policy. From 1931 to 1933, Llopis oversaw major educational reforms and contributed to the training of what would become the most accomplished generation of Spanish teachers. At the heart of his agenda was the opening of new schools. Convinced that teachers were the true driving force of educational reform, he pushed through a decree-law creating 7,000 new teaching posts. After stepping down, he published La revolución en la escuela (The Revolution in the School), a detailed account of his time in office and of the Republic’s educational programme. In 1934, he followed this with Hacia una escuela más humana (Towards a More Humane School), in which he outlined his pedagogical vision—clearly indebted to the Institución Libre de Enseñanza and grounded in the belief that education could transform society. He defended the secular, unified school and placed particular importance on rural schools as the foundation of pedagogical renewal in Spain.

At the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, Llopis was appointed Undersecretary to the Presidency under Francisco Largo Caballero, a fellow UGT member and socialist. He opposed the government of Juan Negrín and criticised the growing dominance of the Spanish Communist Party. In 1939, he went into exile in France, where his French wife, Georgette Boyé, a secondary school teacher, had remained. On his arrival, he wrote: “At twelve o’clock, a train leaves for Toulouse. I head for the station. At five in the afternoon on Sunday, 5 February, I arrived at my home in Albi, where my wife and son were waiting for me, anxious. Exile begins!”

In France, he combined political activism with a strong commitment to education. He founded and presided over the International League of Education, later becoming its honorary president.

During the difficult early years of the post-war period, the French Teachers’ Union and the International Federation of Teachers’ Associations formed a support committee for exiled Spanish teachers. Llopis was appointed its chair. When France fell under German occupation during the Second World War, he was subjected to forced residence in several towns, including Le Chambon-le-Château (1941). After the Liberation in 1944, a congress of exiled Spanish socialists met in Toulouse, where Llopis was unanimously elected Secretary General—a position he would hold for thirty years. In correspondence with socialist organisations inside Spain, he used the codename “Sebastián”. Shortly afterwards, he was appointed vice-president of the UGT. These developments marked the beginning of the PSOE’s reconstruction in exile.

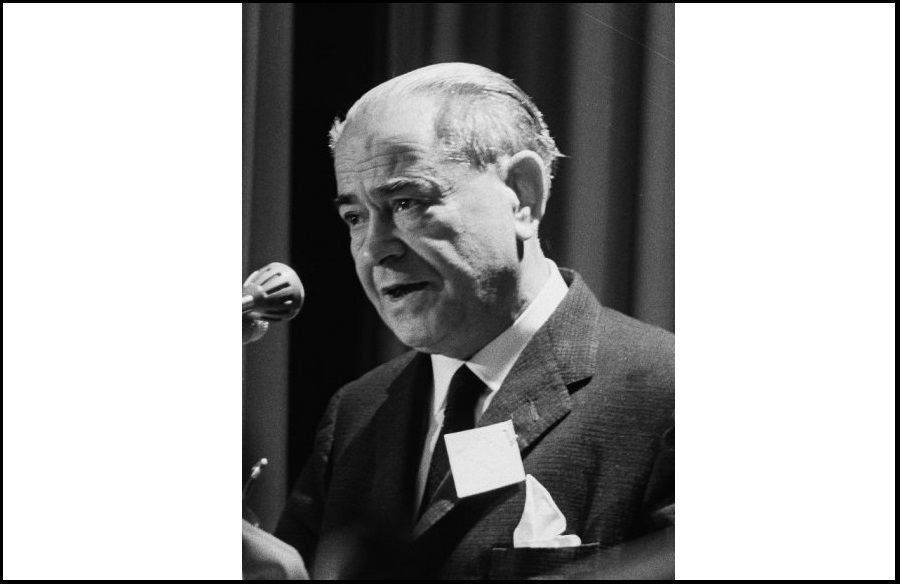

The 13th Congress of the party—the last held in exile—took place from 11 to 13 October 1974 at the Jean Vilar Theatre in Suresnes. The congress marked a formal break with the historic leadership headed by Llopis. Delegates sided with a younger, reformist group operating from within Spain, intent on preparing for a transition they believed was imminent. This group included Felipe González, Alfonso Guerra, Manuel Chaves, Nicolás Redondo and Enrique Múgica.

Yet Llopis did not disappear from public life. In 1977, he briefly returned to Spain and stood as a Senate candidate in Alicante province, though he was not elected. He then returned to France.

Throughout his prolific career, Llopis published numerous works on politics and education, along with a substantial number of journalistic articles.

Rodolfo Llopis died in the French city of Albi in 1983, at the age of 88. According to his son, “he lived two and a half lives. In the first, he was a teacher because he believed that only education could bring about a fairer society; for that reason, he conceived and implemented during the Republic the most ambitious educational reform Spain had ever seen. His second life was that of exile in France, which he dedicated to keeping Spanish socialism alive in order to fight Franco’s regime from Europe through politics. In his old age, Llopis was pushed aside by the younger members of his party, shortly before he was able to return to Spain—a brief homecoming that he experienced with both joy and scepticism”. Today, that remarkable man—now almost forgotten—lies buried in that French city.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons