- Economy

- 29 de May de 2025

- No Comment

- 21 minutes read

Education investment as an engine of economic growth: successful case studies and lessons for Catalonia

Education investment as an engine of economic growth: successful case studies and lessons for Catalonia

- Introduction

The relationship between education and economic growth is well established. Countries that have significantly improved their standard of living in recent decades tend to share a common denominator: sustained investment in education. Such investment fosters an environment where innovation, technology, productivity, and employment can flourish.

However, not all investments in education yield the same impact. In some countries—particularly in Southeast Asia and Northern Europe—the education system has been approached as a strategic national priority. In contrast, Catalonia has embraced a so-called “modern” (in practice, improvised) pedagogical trend based on vague competencies and diffuse methodologies, where academic content seems to have been lost amid the proliferation of “learning domains” and “project-based work”. This trend, which lacks robust scientific evidence, appears to be undermining educational outcomes and could, in the long term, jeopardise both economic competitiveness and growth.

In addition, the widespread introduction of screens in classrooms—replacing traditional textbooks—and the reduction of essential curricular content are troubling trends in our educational system. Beyond impairing the formation of the human capital necessary for economic growth, these new educational methodologies may be fostering more easily manipulated citizens, with diminished critical thinking skills and less preparation for the challenges of real life.

Empirical evidence, as this article will demonstrate, clearly shows that Southeast Asian countries—especially Singapore, South Korea, and Japan—have provided paradigmatic examples of how a demanding and well-structured education system can transform a nation’s productive landscape. The same pattern is evident in Northern European countries such as Norway, Switzerland, Sweden, and Germany, all of which boast high Human Development Index (HDI) scores and elevated GDP per capita. These countries share well-organised education systems in which the teaching profession is highly valued and well remunerated.

- A summary of theories explaining the drivers of economic growth

Economic growth refers to the real increase in a country’s gross domestic product (GDP) and per capita income (GDP per capita). It is one of the principal objectives of economic policy, as it enables improvements in quality of life and reductions in poverty. Several theories have sought to explain its causes, including:

- Investment and Technological Advancement: Numerous economists have demonstrated the strong link between growth and these two factors. From Schumpeter (1942), who attributed economic growth to technological change driven by entrepreneurship and innovation, to Solow (1956), Arrow (1962) and Romer (1990), the consensus is that innovation and technology—when supported by education and accompanied by business investment—foster increased production and employment.

- Institutional Stability: Scholars such as North (1990), Barro (1997), and Acemoglu (2012) have argued that clear rules, property rights, and an independent judiciary form the bedrock of economic progress. It is difficult to attract investment where legal decisions are uncertain or unenforceable.

- International Trade: According to Ricardo (1817), Samuelson (1948), Krugman (1979), and Heckscher-Ohlin (1991), trade enables specialisation, learning, and economic expansion. However, openness to global markets requires adequate preparation—once again, necessitating investment in education. Well-managed trade, these theories agree, enhances long-term productivity and national growth.

- Human Capital: Multiple economists and schools of thought have explored the direct relationship between human capital—defined as the education level, skills, and knowledge of the population—and a country’s economic growth. As early as the 18th century, Adam Smith (1776) observed that a trained worker produces more than one without training. Schultz (1961), Becker (1964), Lucas (1988), Romer (1990) and Sen (1999) expanded upon this notion: investing in education not only raises company productivity, but also yields returns for the entire nation.

These complex economic theories may be summed up rather simply: Education + Stability + Technology = More bread for everyone. However, if education fails, the rest is unlikely to succeed.

- Education as a pillar of economic development: the human development index (HDI) and PISA assessments

As discussed, education is a key driver of economic growth. It not only provides individuals with essential knowledge and skills, but also enhances productivity, fosters innovation, and strengthens a country’s global competitiveness. Recent history confirms that countries with robust education systems achieve high levels of well-being and sustainable economic growth. Conversely, those with weak systems tend to suffer from inequality, social issues, and economic stagnation.

But investment alone is not enough; the quality of education—measured by student learning outcomes and the status and professionalism of teachers—is equally important. Rigorous curricula and academic demands are often central to educational excellence.

One way of measuring the impact of education on economic development is through the Human Development Index (HDI), developed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). It assesses national well-being through three key dimensions: life expectancy at birth, average years of schooling, and per capita income (adjusted for purchasing power parity).

Table 1. human development index (HDI) in 2022

| Country | HDI | Life expectancy | Expected years of schooling | GDP per capita (PPP $) |

| Norway | 0.961 | 83.2 | 18.1 | 78,180 |

| Switzerland | 0.955 | 83.9 | 16.5 | 78,813 |

| Sweden | 0.947 | 82.6 | 16.1 | 60,802 |

| Germany | 0.942 | 81.9 | 15.7 | 58,150 |

| Singapore | 0.939 | 83.6 | 16.2 | 102,742 |

| South Korea | 0.925 | 83.5 | 16.4 | 54,212 |

| Japan | 0.921 | 84.5 | 15.3 | 48,460 |

| Spain | 0.905 | 83.0 | 17.9 | 42,800 |

(Source: Unesco, 2022)

As shown in Table 1, countries with the highest HDI scores—such as Sweden, Germany, Singapore, and South Korea—also display high GDP per capita and extensive years of schooling. Yet, it is not merely the quantity of schooling that matters, but what students actually learn. In this regard, PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) scores offer further insight. Countries that foster a culture of academic effort tend to achieve the best PISA results. Research shows that an improvement of one standard deviation in a country’s PISA scores can translate into a 1–2 percentage point increase in long-term annual GDP growth (Hanushek & Woessmann, 2012). Furthermore, countries with higher PISA scores often have higher GDP per capita (Guzey, 2015).

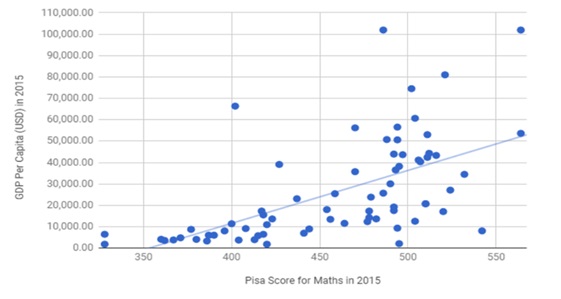

As illustrated in Graph 1, there is a positive correlation between PISA mathematics scores and GDP per capita. Intriguingly, countries that excel in these assessments do not waste time debating whether mathematics “traumatises” adolescents or whether assessments should be “playful and collaborative”. They simply teach, expect effort, and evaluate—this is not magic, but accumulated human capital.

Graph 1.

Corelation between PISA mathematics scores and GDP per capita

Nevertheless, PISA results indicate stagnation or even decline in many European countries, while Asian nations continue to lead. In Spain—and particularly in Catalonia—scores have dropped significantly in recent years (see Table 2). Is this merely coincidental? Perhaps. However, the data strongly suggests that the shift away from academic content is resulting in less-prepared generations.

Table 2. Evolution of PISA Mathematics Results (2000-2022)

| Country | 2000 | 2012 | 2018 | 2022 |

| Singapore | 564 | 573 | 569 | 561 |

| South Korea | 547 | 554 | 526 | 526 |

| Japan | 532 | 536 | 527 | 536 |

| Germany | 490 | 514 | 500 | 487 |

| Norway | 499 | 489 | 487 | 478 |

| Sweden | 510 | 478 | 502 | 487 |

| Spain | 476 | 484 | 481 | 470 |

| Catalonia | 475 | 482 | 479 | 465 |

(Source: OCDE, 2023)

Top-performing countries in PISA assessments—Singapore, South Korea, and Japan—invest between 2% and 5% of their GDP in education (see Table 3), levels comparable to Spain and Catalonia. As noted earlier, it is not merely a matter of investment, but of spending efficiency. Whereas Singapore, South Korea, and Japan have optimised their educational resources through structured programmes and high academic standards, many Western regions have moved in the opposite direction, promoting less rigorous pedagogical models. Catalonia, leading these educational trends, invests only 3.69% of its GDP in education—below the European average and OECD recommendations.

Table 3 Investment in education as a percentage of GDP

| Country / Region | GPD in education | Year |

| Singapore | 2,19% | 2023 |

| South Korea | 4,87% | 2021 |

| Japan | 3,24% | 2022 |

| Germany | 4,54% | 2022 |

| Norway | 3,97% | 2022 |

| Sweden | 7,57% | 2021 |

| Spain | 4,32% | 2022 |

| Catalonia | 3,96% | 2022 |

| OECD | 4,9% | 2021 |

Source: Theglobaleconomy.com e Idescat.cat

The issue, then, is not only financial; it is one of strategic direction. In Catalonia, for example, hours dedicated to mathematics have been reduced to make room for “emotional competencies”, and textbooks have been replaced by aesthetically pleasing digital devices fit for social media. Instead of “learning situations”, perhaps we require “real-life situations”: the ability to divide, write coherently, or explain the law of gravity without confusing it with a personal opinion.

- Cases of Success: Singapore, South Korea, and Japan

Singapore, South Korea, and Japan have developed highly effective education systems characterised by structured approaches, academic rigour, detailed curricula, and substantial public investment.

Since gaining independence from the United Kingdom in 1965, Singapore has prioritised education as a key development strategy. Although its public investment in education is only 2.19% of GDP—below the OECD average of 4.9%—it achieved outstanding results in the 2022 PISA assessments: 561 in mathematics, 543 in reading, and 561 in science, ranking first in all three areas. This success is partly attributed to the “Singapore Method”, which promotes deep mathematical understanding through a Concrete-Pictorial-Abstract (CPA) approach.

South Korea, emerging from war in the 1950s, also made education a central pillar of national development. In 2021, it allocated 4.87% of GDP to education, aligning with the OECD average. Its system combines rigorous public schooling with private academies (hagwon) to reinforce learning. A culture of effort and competitiveness has positioned the country among PISA’s top performers: 526 in mathematics, 515 in reading, and 528 in science.

Japan, one of the world’s most advanced economies, maintains a culture of educational excellence, discipline, and structured knowledge. In 2022, its public education spending was 3.24% of GDP. The system emphasises memorisation and mastery of core content in mathematics and science. In that year’s PISA tests, Japan scored 536 in mathematics, 516 in reading, and 547 in science.

While Asian countries treat education as a state priority with clear objectives, some European contexts are drifting towards more experimental pedagogical approaches.

- Educational Investment in Catalonia: Screens and Unstructured Curricula

Catalonia allocates approximately 3.96% of its GDP to education—below the OECD average (4,9%). Yet the issue is not merely one of financial resources, but of how they are directed. Core subjects such as mathematics and language have seen reduced instructional time, replaced by methodologies that prioritise experience over knowledge, fragmenting curricula and diminishing academic rigour.

The 2022 PISA results reveal a marked decline in student performance in Catalonia: 469 in mathematics, 462 in reading, and 477 in science—below both the Spanish and OECD averages. Over the past decade, the region has lost 24 points in mathematics, 38 in reading comprehension, and 15 in science—an alarming trend.

Moreover, the increasing replacement of textbooks by digital devices has raised concerns. Studies (Delgado, 2018) indicate that reading on paper enhances comprehension and information retention. The lack of a clear and structured curriculum exacerbates the problem, as essential content is often inadequately covered and overly dependent on individual teachers’ discretion.

In contrast, Asian countries such as Singapore, South Korea, and Japan have shown that demanding, structured, and effort-based education is fundamental to economic development. Unless Catalonia reverses its current trajectory, its long-term competitiveness and growth may be compromised. A reorientation towards a model that values knowledge, excellence, and common sense is urgently required to ensure a more skilled and competitive society.

Conclusion: Are We Taking the Wrong Path?

Countries that achieve high growth do not improvise their education systems. They implement clear curricula, support excellent teacher training, and cultivate a culture of effort. Catalonia, by contrast, has opted for pedagogical models that reduce content, lower expectations, and embrace chaos.

If education is about preparing for the future, we may be creating a generation of students adept at drawing timelines and forming teams, yet incapable of reading a mortgage contract or understanding a payslip.

Education is not a laboratory experiment; it is the foundation of our economic competitiveness and personal freedom. Catalonia urgently needs an educational reform that reinstates knowledge, rigour, and common sense. Without high-quality human capital, economic growth will remain little more than an expensive dream.

References:

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1369–1401.

Arrow, K. J. (1962). The economic implications of learning by doing. Review of Economic Studies, 29(3), 155–173.

Barro, R. J. (1997). Determinants of economic growth: A cross-country empirical study. MIT Press.

Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. University of Chicago Press.

Delgado, P., Vargas, C., Ackerman, R., & Salmerón, L. (2018). Don’t throw away your printed books: A meta-analysis on the effects of reading media on reading comprehension. Educational Research Review, 25, 23–38.

Guzey, Z. (2015). Study on the Correlation of GDP Per Capita and PISA Maths Scores in 2015. Academia.edu.

Hanushek, E. A., & Woessmann, L. (2012). The knowledge capital of nations: Education and the economics of growth. Journal of Economic Growth, 17(4), 349–383.

Heckscher, E. F., & Ohlin, B. (1991). Heckscher-Ohlin trade theory (H. Flam & M. J. Flanders, Eds. & Trans.). MIT Press. (Obra original publicada entre 1919 y 1933.)

Idescat. Institut d’Estadística de Catalunya (s.f.). Datos de Gasto en educación. Recuperado el 09-05-2025 de https://www.idescat.cat/

Krugman, P. R. (1979). Increasing returns, monopolistic competition, and international trade. Journal of International Economics, 9(4), 469–479.

Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(88)90168-7

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

OCDE. (2023). PISA 2022 results. OECD Publishing.

PNUD. (2022). Human development report 2021/2022: Uncertain times, unsettled lives: Shaping our future in a transforming world. United Nations Development Programme.

Ricardo, D. (1817). On the principles of political economy and taxation. John Murray.

Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5, Part 2), S71–S102.

Samuelson, P. A. (1948). International trade and the equalisation of factor prices. Economic Journal, 58(230), 163–184.

Schultz, T. W. (1961). Investment in human capital. The American Economic Review, 51(1), 1–17.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1942). Capitalism, socialism and democracy. Harper & Brothers.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Alfred A. Knopf.

Smith, A. (1776). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. W. Strahan and T. Cadell.

Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70(1), 65–94.

TheGlobalEconomy.com (s.f). Datos de Gasto en Educación como porcentaje del PIB. Recuperado el 09-05-2025 de https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/

UNESCO. (2022). Education for sustainable development: A roadmap. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons