- Literature

- 29 de September de 2025

- No Comment

- 12 minutes read

David Aliaga: “A writer does nothing but question identity”

Interview with David Aliaga, writer

David Aliaga: “A writer does nothing but question identity”

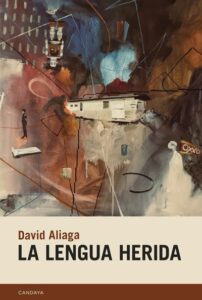

David Aliaga (L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, 1989) has just published La lengua herida (Candaya), a novel that has been especially anticipated. Previously, Aliaga had brought out three short story collections—Inercia gris (2013), Y no me llamaré más Jacob (2016) and El año nuevo de los árboles (2018)—as well as the novel Hielo (Ice, 2014).

I think I’ve been pestering you for almost a decade to bring out another novel, your big novel. And here it is at last. Have you hated me much for that?

Not really, to be honest. Especially if you’re going to call La lengua herida “my big novel” and describe it as “long awaited” (laughs). In any case, the truth is that, just as I try to remain open to the conversation that develops around what I write—because certain readings of my texts allow me to learn, to rethink them—I’ve also learnt to shield myself from the expectations of an editor, a reader, or, as in this case, a friend. If La lengua herida turned out to be a novel, it’s because that was the form that best suited this book. If it had once again been short stories, or an essay, or poetry, I wouldn’t have had too many qualms about making you wait a little longer… (laughs).

Ten years since you published Hielo…

And seven since El año nuevo de los árboles. It turns out I’ve become a slow writer over the years… But I’m at peace with that. I’m aware of this idea that circulates among editors and agents: that a writer who doesn’t publish something new every two years disappears, is forgotten. And, at the pace things are going, if we keep accustoming readers to this absurd voracity, demanding new stimuli every so often, soon it’ll be said that you need to bring out a new book every year, or every six months.

“I spent almost seven years working on La lengua herida because that’s how long it took me to arrive at a version I could feel satisfied with”

But that has to do only with market dynamics, with visibility, with selling books. And I won’t be hypocritical about it: I want as much visibility as possible for my work and to sell as many copies as I can. But that’s a later stage, one that comes after the literature, that has nothing to do with literature itself and therefore interests me less. In this sense, literature is becoming slightly anachronistic: it demands other rhythms, it calls for calm, for thinking about what one writes, letting it rest, questioning it, turning it upside down… I’ve also learnt to shield myself in this regard. Even though from time to time an editor would ask me, or an agency would write, I spent nearly seven years on La lengua herida because that was the time I needed to come up with a version of the novel I could feel satisfied with, one that made me believe it was the best text my knowledge, my talent and my capacity for work would allow me to put into readers’ hands.

How did you work with time in La lengua herida?

In this novel I tried to find ways of writing time that didn’t follow a chronological criterion, that felt vaporous, so that at certain moments the reader wouldn’t know if the narrative was moving forwards or backwards, whether the time was factual or whether it was taking place in thought or in a dreamlike state.

This was important for several reasons. One has to do with a twist in the plot that is revealed in the last chapter, which of course I won’t spoil, but which led me to want to dissolve time—and sometimes space as well—in the narrative, in order to propose a certain kind of experience to the reader.

“One of my aims was to make the reader remain constantly on guard against the text itself, questioning it, staying alert”

Another reason is that one of my aims was to make the reader remain constantly on guard against the text itself, questioning it, staying alert… because La lengua herida is about, among other things, the way we construct reality as discourse, through language. And if reality is constructed as discourse, using language, that means whoever is constructing it can lie to us, can distort it to suit themselves or out of ignorance… including the narrator, and even the author of the novel we are reading.

The world of comics seems to occupy more and more space in your life and in your prose…

Reading comics is something I enjoy and that gives me pleasure. I’ve done it since I was a child, but it’s only in recent years that I’ve integrated it into my writing and professional work, that’s true. The fact that comics have a certain weight in La lengua herida—perhaps I should point out that its protagonist is someone who once wanted to be a comic book artist, and at the moment when the novel begins is taking up that vocation again—began almost as a provocation.

There are still prejudices about comics, snobs who find it incompatible to enjoy, say, the books of Pierre Michon or Pascal Quignard and The Fantastic Four by Jonathan Hickman or Grant Morrison’s Animal Man. So, creating a protagonist who can cite Derrida, Kafka, Carrington or Kerouac as easily as he can theorise about Stan Lee, Steve Ditko or Ed Brubaker’s X-Men was a way of rebelling against that stupidity. But not only that. P. Coen’s relationship with comics is also an important element of his characterisation, one that speaks of his Jewish roots as well.

Who—or what—is P. Coen?

He is, of course, the novel’s protagonist. A character who, as the narrative unfolds, thinks of himself as a Jew, the grandson of immigrants, a father, an ex-husband, a Barcelonan, a comic book artist, a reader, a university lecturer… with all the complexity and contradictions such categories entail.

And who are you?

Are you really asking that of a writer who does nothing but question identity? (laughs) I suppose I’d have to start the answer by saying that I’m someone who, depending on the time of day, thinks of himself as a writer, a Jew, a Catalan great-grandson of Andalusian and Murcian immigrants, a son of Barcelona’s working-class periphery, a husband, a reader… with all the complexity and contradictions such categories entail. (laughs)

Do you still write short stories?

Yes, after finishing La lengua herida I wrote a few stories, though I’m not sure they’ll end up forming a book this time. That’s not my intention at the moment, in any case, but I did feel like going back to writing something shorter. Even though, as I said, I’m at peace with being a slow writer, when I finished the novel, after nearly seven years, I did feel some anxiety at the thought of going through another process that long… It’s been a draining experience. So, while I catch my breath and find the strength to start the next novel—assuming again that writing may take four, five, six years—I’m writing short stories.

“My sense is that more and more voices are making themselves heard that want to impose narrow margins on what one can be”

Why Trieste, why Mexicali?

The three main settings of the novel—Trieste, Mexicali, and Barcelona—share the fact of being spaces that reveal how complex it is to narrate identity. And, again, I chose those places because they allowed me to question the idea of identity as a closed, monolithic, uncrackable discourse. My sense is that more and more voices are making themselves heard that want to impose narrow margins on what one can be, on what it means to be, I don’t know, Spanish or Catalan, a man or a woman… When reality shows us instead that the experience of being is complex, changing, that we are many things at once and that perhaps tomorrow we won’t be exactly the same as we are today. What does it mean to be Triestine, cachanilla [from Mexicali], or Barcelonan? Can we really give a single, fixed, immutable answer to that question without sounding ridiculous?

How do you think or feel about Barcelona, which is also present in your novel?

I think I’ve already answered that in part. In my own imagination Barcelona still presents itself as that place of exchange, of culture, of conversation, of mixture… the place I began to visit as a teenager, coming in from the periphery, trying to quench a certain thirst, to broaden the margins of my experience, because it was the place where culture happened. And although it’s true that the city has declined in recent years, I still think of it and experience it as a forum, in the classical sense of the word.

Is La lengua herida a current of interwoven memories?

That doesn’t strike me as a bad way of defining the novel. As long as we remember, of course, that memory itself is made up of distortions, fictions, challenges…

What are you reading at the moment?

For reasons connected to my work as an editor, these past few months I’ve been reading a lot of Central American fiction. Rodrigo Rey Rosa, Carlos Fonseca, Zee Edgell… Dany Díaz Mejía, who you may have heard of, perhaps because of his work as a journalist. I must admit I hadn’t heard of him until very recently, but I had the chance to read La Quebrada, and I think it’s an absolutely wonderful book. I greatly admire the author’s ability to perceive and narrate the goodness that exists, even if it doesn’t seem so, in contexts of violence. Another of my recent reads has been the chronicle Martha Gellhorn wrote about the US invasion of Panama, which I found very interesting.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons