- Books

- 27 de October de 2025

- No Comment

- 9 minutes read

Connecting Neuroscience with Education. Critical Considerations

Free open PDF: https://brill.com/display/title/72599

Neuroscience in the classroom?

A new open-access UNESCO manual explores the connection between neuroscience and education — a guide to understanding evidence-based education, debunking edumyths, and confronting educational pseudoscience.

In today’s educational landscape, where pseudoscience is on the rise, many teachers remain uncertain about which methodologies are genuinely grounded in scientific evidence — and which rely instead on the so-called ‘evidence’ peddled by the latest snake-oil merchants. Social media and school corridors alike teem with myths and misconceptions about so-called ‘neuroeducation’ and with dubious ‘neuro-hacks’ supposedly inspired by generative Artificial Intelligence (AI). Against this backdrop, the publication of the UNESCO International Bureau of Education’s volume Connecting Neuroscience with Education: Critical Considerations stands out as an indispensable intellectual antidote.

This concise open-access manual — the fruit of Donna Coch and David Daniel’s impressive effort at synthesis — does not seek to impose ready-made formulas but to strengthen teachers’ critical faculties. To begin with, and this is no small matter, its digital version is freely available. Be wary of those who attempt to profit from their professional insecurities in the classroom.

Coch and Daniel’s purpose is crystal clear: to equip educators — from early childhood to higher education — with the scientific tools needed to distinguish solid evidence from mere edumyths, which, as Héctor Ruiz (2023) aptly observed, run rampant through classrooms, often distorting educational practice and ultimately shaping the learning experiences of our young people. It may vary from one context to another, but teachers are by no means immune to pernicious ideologies or to pseudosciences and pseudotechnologies (Bunge, 2013; 2019): that is, bodies of knowledge or technological solutions presented as proven, true and justified when they are not — or offered to solve invented or non-existent problems, sometimes created by the very same people who later sell us the cure. A classic pattern, indeed.

And please, do not turn into moral zombies, as Carissa Véliz (2021) might put it, merely because the book happens to be written in English. In the age of AI, requesting a translation into your preferred vernacular language is child’s play. Its true value lies in its practical orientation: teaching how to think about educational research rather than prescribing what to think. Yet genuine understanding demands effort — reading in a language that is not your own, translating if necessary, rereading, reflecting, recalling and applying in order to internalise and make sense of it.

Scientific literacy as a tool for the educational front line

If pressed for time, start with the first chapter: “Using Research Evidence: Concepts Relevant to Educators”. It should be compulsory reading for those who, even within academia, disregard scientific research in education. It won’t appeal to the peddlers of half-truths, nor to those who twist arguments to suit their own ends and spread fallacies. Science has its limits, of course, but without it, education is left at the mercy of shamans, life coaches, self-help gurus (Delgado, 2014), and tree-huggers alike.

Coch and Daniel explain how years of professional experience inevitably give rise to deep and operative mental models about teaching and learning. While essential to human heuristics, such models are susceptible to biases including belief perseverance, logical fallacies and confirmation bias. Daniel Kahneman (2011) explained this extensively when he popularised—albeit in simplified form, as the Nobel laureate himself acknowledged—the notions of System 1 (intuitive) and System 2 (rational) through which our brain typically operates. In practice, this means that teachers, often unwittingly, ignore evidence that challenges their established methods, allowing certain false notions — or neuromyths — to take root in their classrooms. Self-criticism becomes extraordinarily difficult when we lack time to think, caught in the everyday whirlwind of school life.

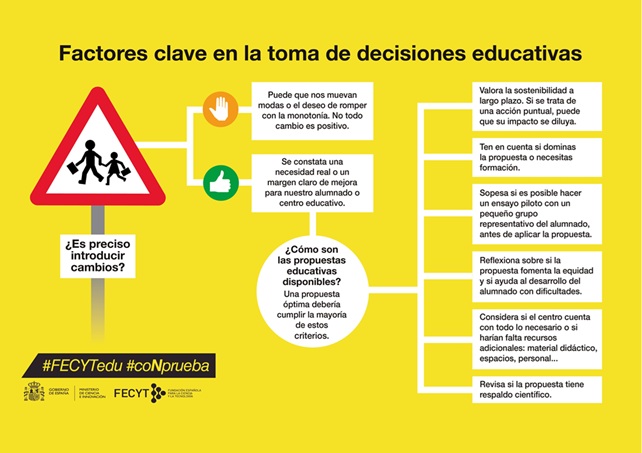

Adopting an evidence-based educational practice should be regarded as a standard of quality, just as it already is in medicine — as exemplified by the Spanish government’s ConPrueba campaign. Education should be no exception. We should all think carefully before embracing new methodologies or reforms devoid of empirical grounding (see Figure 1). Moreover, education inspectors ought to intervene whenever pseudoscientific practices enter classrooms and threaten students’ futures. For, in the best-case scenario, such practices merely waste their precious time — and time, as we know, is gold.

Campaign by FECYT (2020) on evidence-based education. Source: Government of Spain, Ministry of Science and Innovation, FECYT. (Translated into English by the translator)

How, then, can teachers know whether a given proposal has genuine scientific support? They must learn to distinguish, for example, between correlational studies (which only suggest a relationship between variables — correlation does not imply causation), quasi-experimental designs and, most importantly, experimental research such as randomised controlled trials. Understanding the role of replication, control groups and methodological validity allows teachers to move from being passive consumers of information to becoming critical evaluators of educational theory and research (Ruiz, 2020). It empowers them to recognise when a methodology has sufficient evidential grounding to be applied with professionalism and ethical integrity — or, conversely, to walk out of a poorly designed training session, perhaps recommended by an inept management team or by the educational authorities themselves.

At its core, this brief book seeks to foster a conceptual shift enabling teachers to integrate science into their mental models, transforming teaching into an informed, self-reflective yet flexible discipline. I shall not reveal more of its contents, for it is far better that readers discover, step by step and at their own pace, the critical insights Coch and Daniel (2025) offer on the relationship between neuroscience and education.

Teachers, do not settle for what certain influencers — or footballers wearing tinted sunglasses — tell you about neuroscience. Be autonomous; learn to discern for yourselves the boundary between scientific reality and fantasy. In a world saturated with information, where shortcuts and magical solutions are continually promised to the complexity of the art (and science) of teaching, an act of rebellion — and of professionalism — is the adoption of the scientific method.

This is not about stripping passion or emotion from the classroom, but about safeguarding your vocation and your craft through evidence. Stop being passive spectators of pedagogical fads: dismantle the edumyths, be active and uncompromising in your resistance to magical thinking, and claim your rightful place as intellectual figures in the lives of your students. For your pupils’ critical spirit depends, in no small part, on the cultivation of your own.

Títle: Connecting Neuroscience with Education. Critical Considerations

Authors: Donna Coch & David B. Daniel

ISBN: 978-90-04-73531-6

Publisher: De Gruyter Brill / UNESCO IBE

Language: Inglés

Number of pages: 80

Publication date: octubre de 2025

Web (free open PDF): https://brill.com/display/title/72599

References:

Bunge, M. (2013). Pseudociencia e ideología. Laetoli: Pamplona.

Bunge, M. (2019). Filosofia de la tecnologia. IEC-UPC: Barcelona.

Coch, D. y Daniel, D. B. (2025). Connecting Neuroscience with Education: Critical Considerations. UNESCO IBE /Brill. https://brill.com/display/title/72599

Delgado, E. (2014). Los libros de autoayuda, ¡vaya timo! Laetoli: Pamplona.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Pensar rápido, pensar despacio. Debate: Barcelona.

Ruiz Martín, H. (2020). ¿Cómo aprendemos? Graó-ISTF: Barcelona.

Ruiz Martín, H. (2023). Edumitos. ISTF: Barcelona.

Véliz, C. (2021). Moral zombies: why algorithms are not moral agents. AI & Society, 36(2), 487-497.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons