- Opinion

- 20 de June de 2025

- No Comment

- 11 minutes read

Choosing a school, and other propaganda jokes

Choosing a school, and other propaganda jokes

Santiago García Tirado

Choosing a school: that old summer dilemma. Postmodern life thrives on dilemmas and dilemmas. Each one seems expressly designed to unsettle the already fragile peace of mind of individuals, families, and even institutions that once appeared to belong to an eternal order. The hyper-acceleration of history also seems bent on extinguishing all inner calm. Let no one live a single day without being tormented by one or more dilemmas. Each feels inescapable, each appears definitive. The dilemma of choosing your children’s school—and not getting it wrong—is a perfect example.

Choice is presented as the ultimate ritual in a system that calls itself democratic, though it bears little resemblance to the moment of freedom it purports to be. We are influenced—perhaps even determined—by the views of others, by urban myths, and by various shapeshifting superstitions, many of which are based on unverifiable claims but nonetheless shape our judgement. We feel the weight of responsibility, convinced that we alone must confront the truth, yet our democratic will is clouded by a haze of rumour and misinformation.

What I propose here is a pause: to take a breath, to briefly suspend the compulsive machinery of decision-making that now governs our lives—even before we begin to discuss school choice. And what better way to open this interval of clarity than by posing a question: why exactly should we have to choose a school for our children?

We do not get to choose our neighbourhood police officer, nor the district in which we vote, nor the judge who oversees our legal disputes. We cannot choose where we pay our taxes, nor where we are allowed to live—unless, of course, we are rich, and above all, not reliant on a monthly salary. We are compelled to visit the administrative office that corresponds to our area, to endure the smells and hardships of the neighbourhood our income permits. And yet we are led to believe that choosing a school is the ultimate act of freedom, the one decision no citizen must be denied. But again: why should we choose?

Is it not the job of the public authorities to ensure that every school offers suitable conditions to receive and educate our children? Is it not their duty to guarantee qualified staff and the best resources across the board? The school or secondary school in my neighbourhood should be just as good as any other. Why, then, do they introduce uncertainty into the equation? Why do they tell us that, at this precise moment, the citizen must rise heroically to the occasion and choose? Choose what, if all schools are supposedly reliable? Or is it, rather, the authorities themselves who are quietly admitting that some schools—and some neighbourhoods—are less trustworthy, even though they bear the stamp of democratic, European, First-World legitimacy? They are state schools, yes, but… perhaps we should think twice?

And so this pause in the decision-making process leads to another question: are we being told that the dilemma of choosing a school is, in the end, the same as every other dilemma in capitalism—namely, to choose, but to pay?

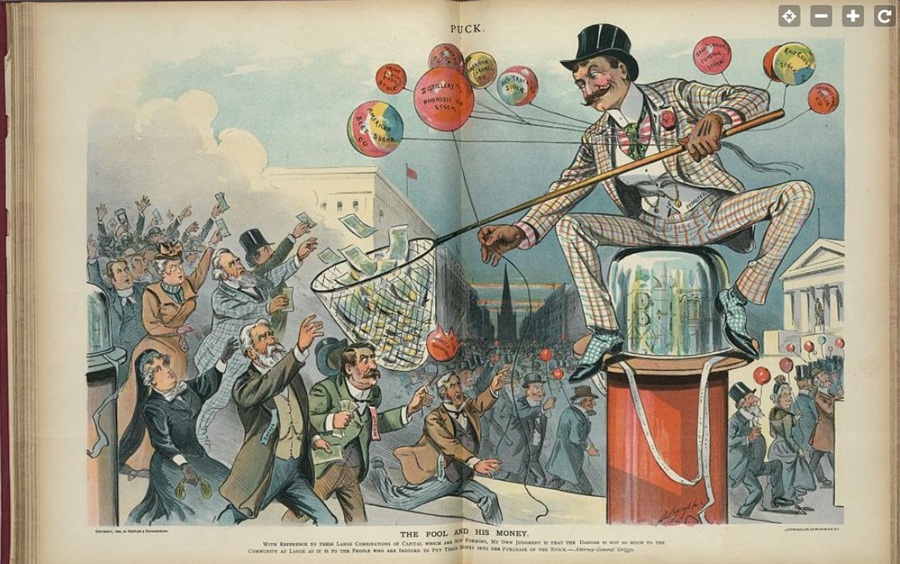

Framed in these terms, it becomes clear that the state functions as an executor of an educational economy driven by interests that are not our own. Interests of the nation, perhaps—but not of those in the nation without money. Seen in this light, the announcement that citizens would henceforth be “free to choose” schools begins to make sense. It marked the start of a new era in which schools were set to compete against one another. Compete? For what? And what cards are they playing—and against whom?

This was the bit that wasn’t made explicit at first. What was left in the subtext was the transformation of state education into a competitor in a deregulated market—because all markets are, to some degree, feral—the new education market. And what better way to hollow out public services than to extract them from a public ethic and hand them over to the logic of speculation and private gain?

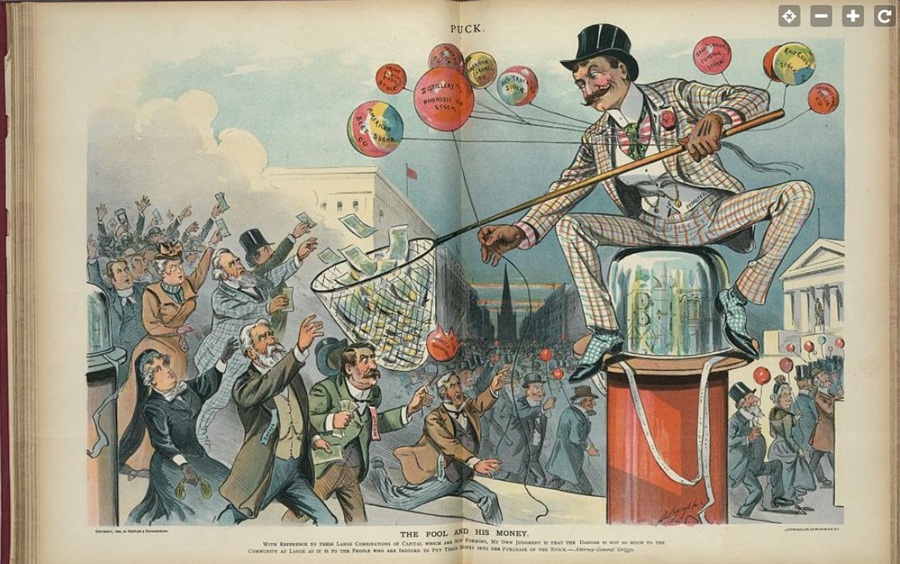

It was a particularly elegant manoeuvre, pulled off at a time when many of us were anaesthetised, still trusting that the people running the state were guardians of the common good. We had no understanding of brand crises, market distortions, promotional lies or hostile takeovers. They told us the times demanded adaptation, and that meant competing with one another. We found it puzzling. We didn’t quite understand—because the key detail hadn’t yet been revealed: that the real dilemma facing families, and anyone with children, was the same old capitalist dilemma—whether or not to buy.

And that’s where private schools had already made their move: by marketing their enrolment plans under a veil of propaganda.

Decades of dismantling state education—and of silencing the alarms sounded by teachers—cannot be chalked up to mere carelessness. There was, though we didn’t realise it at the time, a purpose: profit. And the vast, expanding education market was perfectly poised to cash in on the manufactured disrepute of the public system.

Over time, a subtle propaganda campaign—often disguised as journalism—has taken root, reminiscent of the way the media stokes fear about squatters. It has cemented an image in the public imagination of state schools as violent, chaotic spaces, inhabited by burnt-out teachers and out-of-control students.

The “worst of the worst” is said to dwell in these places for the poor: our state schools. No one with a few extra euros and a measure of upward ambition would dream of sending their child to such schools, where everything is supposedly grim and filthy. At least, not if they’ve absorbed the massive propaganda operation unleashed in recent decades against the state schools.

For the truth—the real, verifiable truth—is that state school remains the best, healthiest option. Denying what is plainly evident has only been possible through propaganda. That, after all, is what propaganda is designed to do: to obscure reality, to ensure that common sense and truth do not triumph over superstition. To bury the self-evident beneath a glowing veneer of fabricated truths.

As I write, my news feed scrolls by at speed: mid-year school transfers are on the rise; the main cause is bullying. Reports of bullying in private schools are appalling, though conveniently unquantified. Another article addresses pupils labelled “NESE B”—those with special educational needs due to economic hardship. Data show they are increasingly being funnelled into publicly subsidised religious schools. Even there, families often cannot afford to stay. They are sent with state money, only to meet with constant “voluntary” fees. These are families who simply cannot afford them. And so, the “system of excellence” gently encourages them to leave.

That same day, my son invites a new friend over. His family is Peruvian, middle-to-upper class, recently arrived in Spain. They too were initially swept up by the propaganda and enrolled their children in a privately-funded state school. Within a few months, their son became the target of bullying. The school refused to intervene, and the other parents dismissed it as “kids being kids”. The boy now attends a state school with my son and seems happy. His older sister remains in the private school. And catholic. On her latest school trip, the students were told to keep quiet about the drunken behaviour that occurred: “what happens in Switzerland stays in Switzerland”.

Later that evening, I speak to my niece, a primary teacher at a German-language private school. She is facing mobbing—workplace bullying, to use the technical term. Being a private institution, what happens in the school, stays in the school. Parents are told the conflict with the management stems from her inexperience. She is young—but also a former pupil and one of the school’s best graduates. Rumours circulate to discredit her. Transparency has no place in propaganda. She is now pursuing legal action, paying both lawyer and psychologist out of her own pocket. She has decided her professional dignity is worth it. Naturally, none of this features in the school’s promotional material. In private schools everything is always exemplary, and the teachers, obedient individuals who respond well when the whip is cracked”.

Elsewhere, a group of nine contributors to La Vanguardia recently published a piece asserting that Christian private schools are distinguished by their superior values. The implication, of course, is that state schools—open to all citizens regardless of class or circumstance—operate without values or excellence. Nobody seems to notice that state schools cater equally to the diligent, the disruptive, the eager, the traumatised, and the vulnerable. Everyone deserves a chance—or a hundred chances. That is the purpose of a state education system. But propaganda tells a different story, erecting a parallel universe where such people do not exist—because they do not conform to “values”. Nuance has no place in the rhetoric of excellence.

Another news item—again from these very days—reveals what now appears to be standard procedure in private and semi-private schools when their reputation is at stake. The case: a group of boys masturbated and sexually assaulted a classmate during a school trip to a sports competition in Málaga. The school is in the affluent Ensanche district of Valencia. The incident happened in 2023, but it is only now reported that just one pupil has been formally charged. The victim had previously suffered repeated assaults and was threatened into silence. The case is chilling—yet it took place in a school allegedly rooted in “values”. “Values” is a popular word among Valencia’s establishment—perhaps because it somehow rhymes with “balls”. The victim was hospitalised for 35 days in La Fe, but the school did nothing to support him. It had a brand to protect.

In this fog of dilemmas, the school system faces at least one genuine choice: whether to continue in habitual silence or to embrace publicity—to make its daily work visible. Because day after day, in the quiet of classrooms, stories unfold—luminous stories that never make it beyond the school gates. Schools are involved in scientific, journalistic, historical, ecological, theatrical, and technological projects, not to mention community service—all of which generate genuine symbolic capital. These achievements deserve recognition. Many schools even take their work onto the international stage, through digital exchanges and trips abroad where no pupil is excluded for lack of money.

These stories must be told because hostile propaganda can only be countered by proudly publicising the work done in state schools. Not only for the sake of reputation, but because every state school has a duty to its neighbourhood, its city. And to do that, it must give something back—through storytelling. In our case, making state education public again means putting it into words. As with so many other endangered goods today, publicity must once again become a public good.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons