- Face to face

- 15 de December de 2025

- No Comment

- 11 minutes read

Xavier Ros Oton: “Mathematical talent is not being properly identified”

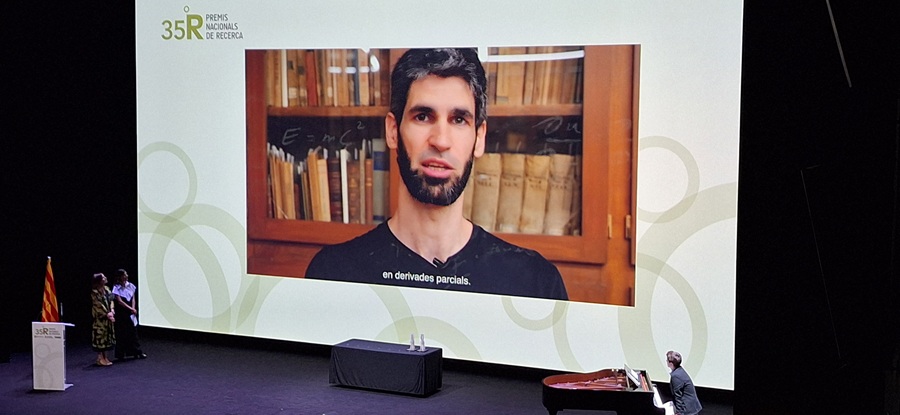

The mathematician, professor and researcher Xavier Ros Oton. / Photo: Courtesy of the author.

FACE TO FACE WITH

Xavier Ros Oton, recipient of the 2025 Premi Nacional de Recerca (National Research Prize)

On 17 June 2025, the Government of Catalonia presented the Premis Nacionals de Recerca at the Teatre Nacional de Catalunya. As I watched the ceremony unfold, one laureate stood out—not only for the weight of his scientific achievements, but also for the striking combination of youth (he has yet to turn 37) and intellectual courage.

Born in Barcelona in 1988, Xavier Ros Oton is widely recognised as one of the foremost mathematicians of his generation. A graduate in Mathematics from the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC), he completed his doctorate there at just 24. His trajectory has taken him from Princeton to Chicago and Zurich; today he is Professor of Mathematics at the University of Barcelona and an ICREA Research Professor. His work centres on partial differential equations (PDEs), a field whose ramifications span physics, biology and beyond.

Ros Oton’s contributions have earned him numerous accolades—the Rubió i Balaguer Prize, the Antonio Valle Prize of the Sociedad Española de Matemática Aplicada, the Fundación Princesa de Girona Award, and most recently the Premi Nacional de Recerca. Despite his youth, he has reshaped our understanding of the regularity of solutions to nonlocal equations, shedding light on structures that, until recently, lay entirely beyond mathematical reach. But he is also a thinker committed to public life, scientific outreach, and our educational system. Speaking with him for Educational Evidence felt indispensable.

You have just received the 2025 Premi Nacional de Recerca. A remarkable distinction, of course. Yet beyond the personal honour, what place do mathematics occupy in the broader architecture of knowledge? What does this recognition signify for you?

It has been a profound joy on a personal level, but also a meaningful acknowledgement of mathematics itself, especially as this is the first time a prize of such stature has been awarded to our discipline.

Awards of this kind often gravitate towards more visibly applied sciences—physics, chemistry. The fact that mathematics, in all its abstraction, has been recognised this time sends, I imagine, an encouraging signal to young researchers like yourself. Your work on nonlocal equations has garnered international attention. Could you explain, in accessible terms, what is at stake in these advances?

To many, mathematics appears forbiddingly abstract, yet the partial differential equations I study underpin weather forecasting, aircraft aerodynamics or the design of a new generation of GPS systems. My research develops the mathematical framework that physicists or engineers can draw upon to build technologies that shape our immediate future.

“My research develops the mathematics that physicists and engineers can draw upon to build more efficient technologies for our immediate future”

Nonlocal equations describe phenomena in which what happens at a point depends not only on its neighbours but also on distant regions—a long-range influence evident in population dynamics, finance or quantum mechanics. Your work has examined the behaviour of their solutions, unveiling regularity features unimagined only a few years ago. How did your journey into research begin? Was there a remote, seemingly unrelated moment that set you on this path?

For me, that remote moment was participating in the Cangur mathematics competition and in the mathematics olympiads. They exposed me to a form of mathematics utterly different from the small dose we encountered at school. In those contests I discovered that mathematics could be immensely enjoyable when approached with time, patience and thought. Both dimensions—the pleasure and the intellectual labour—captivated me.

At school you were drawn to logical problems. Did this require teachers with deep expertise who encouraged free and critical thinking? Or can a pupil learn this independently under non-specialist teachers?

We need deeply knowledgeable teachers who can guide pupils towards the fullest understanding. It is extremely difficult for a non-specialist teacher to allow pupils to “discover” things meaningfully on their own. In the Cangur competitions I met remarkable teachers whose profound expertise enabled them to guide their students with precision—something impossible without that depth of knowledge.

“We need deeply knowledgeable teachers who can guide pupils towards the fullest understanding”

When you reached university and realised you could devote yourself professionally to deep mathematical questions, I imagine it must have been revelatory. Does one choose mathematics, or does one fall in love with it?

I believe it is ultimately a choice already made. Before choosing mathematics at university, I knew perfectly well what I wanted. In a sense, I loved mathematics before I ever arrived at university.

In the United States—particularly before the Trump era—funding was stable, teaching loads were reasonable, and the academic environment genuinely nurtured young researchers. In Spain, by contrast, one often encounters bureaucracy and precarity: the talent is there, but the structures needed to sustain it falter. Having worked at leading international universities, what differences stand out to you?

There are three main differences. First, the extreme bureaucracy we face here—something you do not encounter in the US or Switzerland. Second, the lack of stable career paths for young researchers. And third, the composition of departments: relatively few young doctoral students, and a preponderance of senior academics. In Spain, recruitment aften arrives in waves—sudden burst of hiring followed by protracted periods of near paralysis.

Critics often argue that expectations in our school system have sunk to unprecedented lows, and that there is a strong tendency—reinforced by the LOMLOE—to ensure pupils pass at almost any cost. You have spoken critically about the Spanish education system. What, in your view, is in most urgent need of repair?

In mathematics, at least, we lack teachers in secondary schools who truly master the subject, and this is acutely visible in classrooms. Another issue is that pupils know less and less calculus, and increasingly lack reading comprehension—an essential tool for knowledge”. This is a generalised problem that should prompt a rethinking of the system. Moreover, curricula are poorly structured, and many teachers lack adequate specialisation.

“Secondary pupils know less and less calculus and increasingly lack reading comprehension—an essential tool for knowledge”

Are the sciences fundamentally rote-based? Or should creativity and critical thinking come first?

Memory, creativity and critical thinking must coexist—but memorisation must come first. Creativity can flourish only once techniques and knowledge have been fully internalised. You need to assimilate scientific reasoning before you can develop critical or creative thought. Memorisation lays the foundation; and creativity and critical thinking rise from it. In music, one first learns the stave and the scales; only then does composition become possible.

Mathematics, at least as I practise it, demands calm, mental structure and intellectual honesty; it teaches me to reason rigorously, to distrust my intuitions, and to seek beauty in the abstract. In a world saturated with screens and continual stimuli, how can we help pupils learn to think well?

What matters is being fully absorbed in the problem before you. At that moment, screens are of little use—paper and pencil are far better for sketching ideas and hypotheses without the distraction of a mobile phone or computer. Later, the computer may become helpful. But the essential truth is that genuine learning only happens after prolonged, focused thought.

“Genuine learning only happens after prolonged, focused thought”

Is mathematical talent properly identified and nurtured in schools? Do pupils capable of excelling in logical thinking remain invisible in the classroom? Can they thrive in a system designed for the average pupil?

Mathematical talent is clearly not being properly identified. Even when a pupil excels, they are rarely offered anything more; instead, they are left to their own devices, and inevitably to boredom.

I imagine we need mathematically knowledgeable teachers able to detect such talent from primary school onwards—to recognise that beauty of mind. In your interviews and writings, you often refer to the “beauty” of mathematics. What does this beauty mean to you?

I have always said that mathematics has both a practical side and a side of pure beauty, which very few people see. Consider, for instance, the Pythagorean theorem illustrated in three simple diagrams: to me, that proof is a source of delight. Sadly, such moments are rare in schools, where time is scarce and teachers do what they can. If curricula allowed more room, I believe many more pupils would be drawn to the subject.

When one sees an elegant mathematical proof and truly comprehends it, everything clicks together like a perfect mechanism, producing an aesthetic experience akin to listening to a Bach fugue—its symmetry, its hidden architecture, its depth. How can we nurture this sensibility in primary education?

Primary school is too early, I think; not the right stage. It is better in the first years of secondary school, when one can present the Pythagorean theorem and pupils can genuinely understand it. Then they can perceive the beauty and coherence of a theorem. Geometry offers us many proofs that require no memorisation—purely visual geometric arguments that dispense with abstract mathematical language. This makes the subject more accessible and more pedagogically effective; abstraction can come later.

“In mathematics, job opportunities abound—AI, banking, journalism…”

What advice would you offer young people drawn to research but fearful of the uncertainty of an academic path?

I would tell them that if they love science but fear uncertainty, they should remember that scientific degrees provide excellent career prospects and often higher salaries than the humanities. In mathematics, opportunities abound—in AI, banking, journalism… Science opens many more professional and economic doors than other fields. I would wholeheartedly encourage them to pursue scientific studies.

As a scientist, I dream of a society that values science not only for its applications but also for its capacity to humanise—to sharpen our thinking and help us progress beyond groundless pedagogies and ideologies. What scientific dream would you like to see realised in the coming decades?

I would like AI algorithms to generate something genuinely positive for people’s lives and for society as a whole.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons