- IdeologyPolitics

- 30 de April de 2024

- No Comment

- 17 minutes read

Xavier Massó: “Educationally, we are entering the «esperpento»”

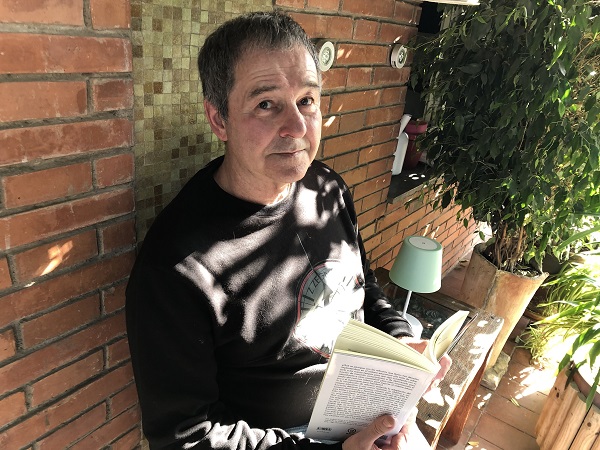

Xavier Massó: “Educationally, we are entering the «esperpento»” (1)

Interview with Xavier Massó, author of the book El fin de la educación (The End of Education). Interview published in the Fundación Episteme, April 6, 2021

Eva Serra

In the face of a confusing landscape of pedagogical innovations, Xavier Massó clearly presents in El fin de la Educación. La escuela que dejó de ser (The End of Education. The School That Ceased to Be) (Akal, 2021) the reasons that have contributed to transforming Western educational systems. An essay that provides a philosophical, historical, economic, cultural, and social critique to unravel the current educational framework which, in his opinion, is increasingly distanced from the enlightened spirit that illuminated Europe.

Xavier Massó Aguadé (Tarragona, 1959), holds a degree in Philosophy and Educational Sciences and in Social and Cultural Anthropology and is a Professor of Secondary Education specialising in Philosophy. He is currently the general secretary of Professors de Secundària (aspepc·sps) and president of Fundació Episteme. Having dedicated nearly three decades to the educational sector, Massó participates in various written press, radio, and television media outlets, as well as speaking at various educational forums.

What has the school ceased to be?

It has ceased to be a place of equal opportunity education, where knowledge was imparted regardless of one’s social, economic, or cultural background. The term “elite school” once referred to the social background of its students, not the mathematics being taught, which were uniform across all schools. Today, however, one’s education can be classified as first, second, or third-class, depending on the school attended.

It has ceased to be a place of equal opportunity education, where knowledge was imparted regardless of one’s social, economic, or cultural background

This occurs under a ‘comprehensive’, pretextually permissive and pretendedly rights-based system, where everyone is said to be on the same boat. However, the reality is that the first, second or third-class cabins of this boat are pre-assigned, leading to a round journey that returns to the same starting point. The comprehensive school, far from being a solution, is a significant part of the problem.

Does the current educational design primarily target the working class?

Undeniably, they are the scapegoats. It’s a model that can be defined as a perfect class aggression in social terms. But it also affects the global population. It’s a system designed with strictly instrumental purposes, tailoring each individual for a specific role.

Are academic contents now held hostage by the new education?

Can their rescue only be attempted from a certain economic position? Well, it could certainly be perceived that way, although in my opinion, it’s even worse due to the social stratification involved. It used to be said that the family educated and the school taught. While not a precise distinction, it intuitively captures the roles of these two institutions. Now, we’re told that the school should not teach but educate, or not only teach but also educate, as if teaching mathematics wasn’t a form of education!

It’s not just that academic contents are now hostages of education, but they’ve been eradicated because they’re considered superfluous for a large part of the population

It’s not just that academic contents are now hostages of education, but they’ve been eradicated because they’re considered superfluous for a large part of the population. As Mrs. Celaá and her “palatial clique” claim, the important thing is not to know a lot, but to know what you know and what you don’t know. A very vulgar statement, and a poor imitation of Socrates’ “I only know that I know nothing”; because the more we know, the more aware we will be of how much we ignore and the need to know them. If Mrs. Celaá intends to emulate Socrates’ quote with this little phrase, the only thing she proves is that she has understood nothing and that she herself does not know what she ignores. This, at the helm of a ministry of education, makes her a public danger.

Why does pedagogical innovation receive so much applause?

There are many factors at play. On one hand, there are the currents that I call the apostles of the ‘good new education’ and those of the ‘theocnology’ in The End of Education. Their innovations are already rather worn out, but they sell a narrative that someone has bought and has taken care of propagating. In essence, it’s “educational populism” in its purest form.

The problem is not these fossilized innovators – charlatans, deceivers and enlightened ones have always existed -, but who has invested them as ‘pedagocrats’

In reality, what we are dealing with are syncretic intellectual snippets, often discarded, whose success is rooted in their role as sustenance within the trophic-pedagogical cycle for authentically predatory and socially hostile models. These models, in turn, disguise themselves beneath the friendly garments of their unfortunate victims. I am referring to educational economism, which is at the top of this ‘pedatrophic’ chain. The problem is not these fossilized innovators – charlatans, deceivers and enlightened ones have always existed -, but who has invested them as ‘pedagocrats’.

How is the intricate network that underpins the current educational system constructed?

It’s a complex web with numerous many interests at stake, operating under its own unique logic and cloaked in a congenial, highly persuasive narrative. It’s often easier to attribute failures to external factors rather than acknowledging one’s own shortcomings or mistakes. This is akin to the ‘love bombing’ technique used by cults to indoctrinate their followers. While this is a human and somewhat understandable tendency, the issue arises when there’s no counterbalance due to the abdication of state and public authorities from their fundamental duty: to maintain a high-quality, egalitarian public education system – as expressed in the vernacular of the old republican school. Society, too, has largely abdicated its responsibility.

The Spanish educational system is an offshoot of the European one, rooted in constructivism. What could be the key to understanding the reversal of the Enlightenment in Europe?

Constructivism is something somehow fresh, and intriguing. No educational system explicitly declares itself a proponent of a specific pedagogical or psychological theory, and without compensatory mechanisms for the evident deficiencies of the comprehensive school that the constructivist model postulates, except for the Spanish one.

The anti-Enlightenment reversal is undoubtedly a global phenomenon tied to the rise of anti-intellectual discourses associated with neoliberalism

The anti-Enlightenment reversal is undoubtedly a global phenomenon tied to the rise of anti-intellectual discourses associated with neoliberalism, even though they seem to be posited against it. In the book, I offer a hypothesis as to why, which I don’t have the space to elaborate on here. In summary, it’s a phenomenon related to the process of neomedievalisation – which is what I believe that we are heading towards – a ‘feudaloid’ society with new technologies at its service. In Spain, this phenomenon is much more pronounced, and its destructive effects too. I believe that this is largely due to the weak reception of the Enlightenment tradition in Spain, both on the right and on the left.

In your book, you invoke three educational meanings, let’s explore the first: end as objective or purpose. Could you provide a brief summary?

Educational systems were established with the goal of imparting knowledge that, due to its nature, an individual cannot acquire in their immediate environment and that necessitates a prior process of instruction. This was the original intent behind their creation, and it remains so. Generally, one cannot independently learn Newton’s binomial theorem, theoretical physics, or ancient Greek, neither with the internet nor with any other means; these are all hoaxes. An ad hoc institution is required, and this is the educational system.

The second end, as limits and domain. Is this meaning educationally immutable or does it allow for more flexibility?

It’s not that it’s immutable, but rather that it ceases to function when these limits are pushed. A domain is defined by the potential to perform a certain function, and this has inherent limits. Miracles are for Lourdes. There’s a difference between instructing in mathematical knowledge and “teaching” happiness. The former corresponds to a specific field of education; the latter, while a commendable aspiration, is beyond the school’s capabilities. What the school can do is teach to understand the world; what it cannot do is teach to be happy. If we persist with the latter, we risk distorting the former. It’s not a matter of incompatibility, but of qualitatively different domains. A swimming pool is for swimming, not for playing football; a hospital is for healing the sick, not for making them happy. If healing them brings them happiness, all the better, but it’s not their primary objective. Let’s abandon our prudish mysticism.

Finally, the end as a conclusion or destruction. Could we already consider education as finished?

Regrettably, I fear so. At least in the form it has taken since the Enlightenment. Particularly in the human dimension of the definitive, which the Prince of Salinas – the protagonist of The Leopard – astutely defined as spanning a couple of generations. It’s challenging to dismantle something that functions well, and even more so to restore it to working order. Of course, this is assuming that there is a desire to do so, which currently doesn’t seem to be the case among those who could potentially champion it. Frankly, I’m not very optimistic.

To illustrate the three ends of your book, it embarks on a historical, philosophical, political, cultural, and economic journey. Could you briefly summarize their role in education?

From a historical perspective, it’s about what education has been, how it originated, and the path it has followed. Philosophy provides the reference criteria to navigate what is and what it ought to be. Politics reveals the motivations and interests that have led to a variety of educational models. Culture addresses the right to education and its significance. The economy delineates what education should not be. I would also include science, which facilitates the transmission of knowledge which makes the world intelligible.

You also conduct a thorough anthropological review, from primitive societies to Levi-Strauss, Margaret Mead, and Clifford Geertz. How have these authors influenced education?

In my opinion, the role of anthropology, or anthropologists, and their influence on educational discourses has often been overlooked, overshadowed by pedagogy, psychology, sociology, and more recently, economics. However, their contributions have been pivotal in many instances, both in terms of narrative construction and laying the groundwork for subsequent educational discourse. As can be inferred from reading the book, I perceive Margaret Mead’s role as somewhat naive, hippiesque, yet crucial in refreshing the old Rousseauian narrative of the noble savage, which appeals to some. Levi-Strauss’s role is far more potent and, frankly, subtly toxic. As for Geertz, I adopt his definition of culture, which I find very practical and relevant.

In your book, you refer to ‘theocnologists’ as those who construct a new theology from new technologies, and the fascination of the simple as a religious equivalent. How would you define the so-called “digital culture”?

If Culture, following Geertz’s perspective, is a tapestry woven from threads of meaning, which we interpret through a learned system of codes – ranging from behaviours and attitudes to scientific knowledge – and digital devices serve as tools that we use for various purposes, then digital culture can be perceived as a universe of meanings that are transmitted to us and accessed, either wholly or partially, through these mediums. The problem arises when the medium becomes an end in itself and the tool itself becomes ‘the code’. Then, instead of being at our service, we put ourselves at its service. This is the essence of Isaac Asimov’s brilliant metaphor in his captivating story The Feeling of Power, which I discuss in the book.

When we surrender ourselves to the medium we have created, reversing the relationship of subordination, this is ‘theocnology’: an instrumental theology with new technologies as a pretext. As Asimov suggests, we no longer need to know how to multiply because the computer does it for us. It doesn’t take a genius to see the underpinning of a highly aggressive social engineering project in all of this, which dilutes the individual in their social function, as Santayana already detected in the thought of John Dewey, one of the most historically celebrated pedagogues.

“The kind discourse”, “The invisible enemy”, you speak of farce. How can it be reversed? Is it possible?

Farce emerges as a social phenomenon when reality degrades, and consists of the conscious pretence that denies this degradation for whatever reasons that induce us to persist in what is not believed. Whether to preserve one’s own position, due to the inertia of the deterioration process that grips us, or also, to duly safeguard the genuine objectives pursued with this deterioration. We must never forget that, faced with opposing objectives, notions of success and failure are interchangeable. What may seem like a failure to me may be a success to someone else. It’s simply a matter of objectives.

The worst part of this farce is the ‘esperpento’, which arises when the degraded reality itself is internalized as a criterion of reference. Educationally, we are entering the grotesque

The worst part of this farce is the ‘esperpento’, which arises when the degraded reality itself is internalized as a criterion of reference. Educationally, we are entering the grotesque, hence the reference in the book to Monty Python. Because the only way out of the grotesque is through irony, establishing a distance with respect to oneself and the situation, exaggerating it so that it shows in its absurdity, in what it has of grotesque deformation.

The invisible enemy? There is a sentence that I read as a child, I don’t remember where, but I think it came from Baudelaire, that impressed me: the devil’s best trap is to convince us that he does not exist. Or Sherlock Holmes when he said that if the plausible does not serve us to explain something, we will have to start thinking about the implausible and under what assumptions, perhaps not previously contemplated, it becomes plausible. It is not about conspiracy theories, but about objective facts: there is an internal logic to successive educational innovations that leads to progressive degradation. And that the commodification of education, its conversion into a market good subject to supply and demand, is the destination towards which it is pointed, does not seem to be objectively questionable… as long as, of course, we know how to distance ourselves from the farce or the grotesque.

To make it clear, when Mrs. Celaá proposes as the objective of her new law to combat school failure by lowering content and approving by decree, she is either completely farcical or simply ridiculous. She is farcical if she is still aware that this is the only way she will improve statistics. She is ridiculous if she really believes that school failure is fought with cooked statistics. In any case, we are educationally facing a real anti-Enlightened despotism.

___

1“Esperpento” is a literary style first established by Spanish author Ramón María del Valle-Inclán. This artistic technique consists of distorting reality in an attempt to reach the authentic being, the ultimate essence of people, things, and situations.

___

For more information:

Link to the webinar held on April 14th

Link to the book (Akal)

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons