- Opinion

- 25 de June de 2024

- No Comment

- 7 minutes read

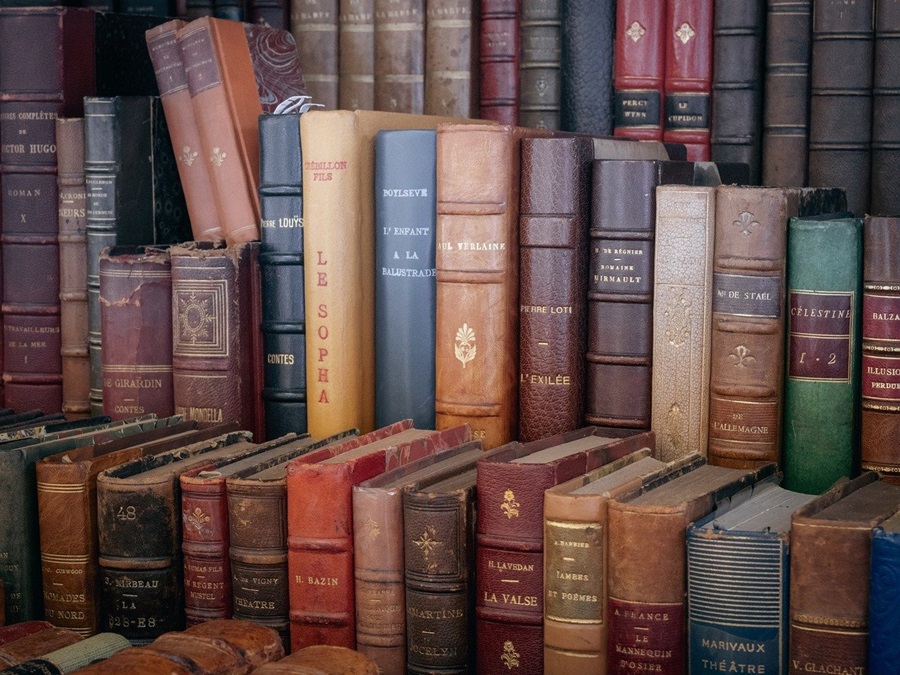

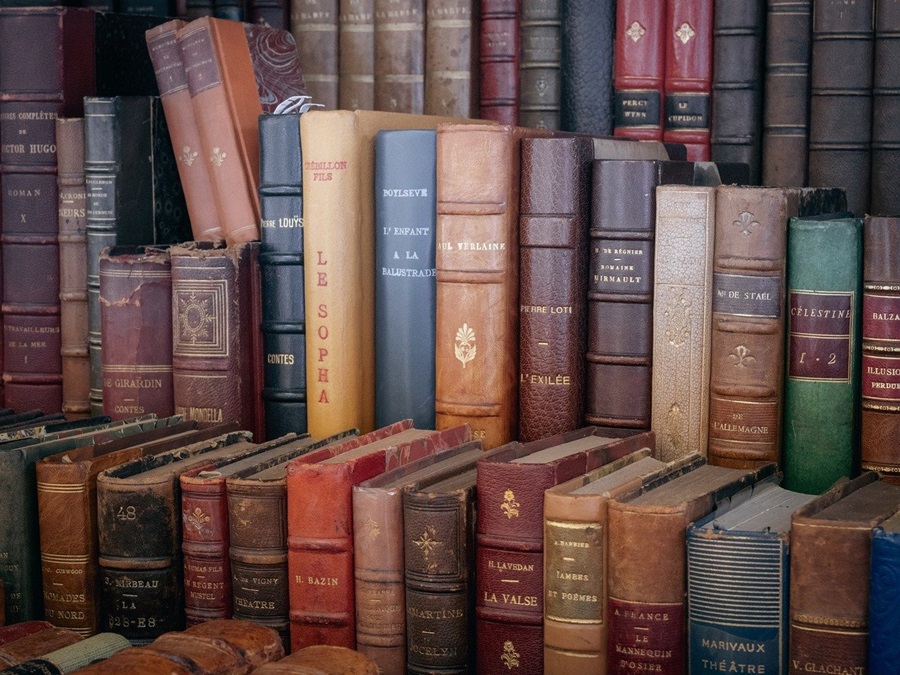

What You Lose When Your Books Are Stolen

THE GREAT SCAM. Opinion Section by David Cerdá

What You Lose When Your Books Are Stolen

We will not be able to incite indignation if people do not understand what they are losing

The gradual disappearance of books from students’ lives is often mistakenly hailed as progress, yet it represents a sentimental and intellectual regression. We surrender the bounty of their emotional and intellectual richness, as well as their critical and creative capacities, in exchange for superficial distractions that transform them into ideal consumers and compliant subjects.

For many years, I have taken it upon myself to introduce my students to the world of books. I teach, among other things, upper-level courses to students aged between 18 and 21, with some as old as 24. My mission has been to encourage them to start reading. Many students, upon entering tertiary education, admit—sometimes with a sense of pride, that I attempt to stifle —that they have read only a few books in their lives and none in the past year. This scenario is now more common due to the declining standards of secondary education, overt or covert government policies aimed at promoting great progression, and the prevalence of websites like Elrincondelvago. It is now entirely possible to complete secondary education without ever having read a book.

Netflix once famously stated in a strategic plan that its main competitor is not HBO or Prime, but sleep. Implicitly, Instagram and TikTok’s competitors are books. To sustain the lavish lifestyles of figures like Mark Zuckerberg and support the privileges of the Chinese Communist Party (which does not permit such frivolities on its own platforms but rather maintains Douyin under strict regulations), it is essential that neither youth nor adults engage in reading—and they are succeeding in this endeavour. We allow this cognitive theft, this theft of life itself, with indifference, citing misguided appeals to modernity, changing times, and “new formats”. In our country, the situation is so dire that some even applaud teachers who incorporate TikTok into their teaching methods.

This is theft in which the victims applaud: the most insidious kind of theft. I recall a day when I was explaining this in class, and a student protested, saying it was not theft since she enjoyed being robbed. Here lies the dangerous novelty and the difficulty some have in understanding where the crime resides. However, there is hope in the rebellious spirit of youth, who naturally and rightly tend to rebel – or used to, for we have never before had a generation so adapted to the system, so docile. It is our fault, the fault of their elders.

What exactly is being stolen from you when your books are taken away? I suspect this is what we are failing to convey adequately. We will not be able to incite indignation if people do not understand what they are losing. A sensu contrario, it is common to encounter the assertion on social networks or in casual conversation that “Books do not make you a better person”. Let us set aside the obvious fact that there are well-read scoundrels and that there is no direct cause-effect relationship, nor even a perfect correlation, between moral character and the quantity or quality of one’s reading. Books do not necessarily make you a better person. They make you freer. They enhance your capabilities and critical thinking skills. They enrich your vocabulary, thereby providing additional possibilities for thought and making you more intelligent. They improve your professional prospects and open up worlds of imagination. They cultivate your sensitivity and deepen your understanding of the human condition. Moreover, they improve your concentration and attention, serving as effective personal coaches in the cognitive field. Similarly, they boost your creativity. This is what books do for you.

How does this wonderful technology called the book achieve such remarkable benefits? On one hand, there are haptic aspects related to touch. We often say we caress their pages and we are not exaggerating: there is an intimacy between skin and paper that brings us closer to what is written encouraging us to immerse ourselves in its content. Printed paper also strains the eyes the least, a disadvantage that digital ink addresses more elegantly than computers, phones, and tablets. On the other hand, there are important cognitive reasons. The book is designed to force us into lucid isolation. There are no other stimuli competing with reading; no moving objects, no sounds, no excessive colours, as found in all internet-connected devices. Reading a book is an act of internalisation, accessing our innermost depths while simultaneously opening us to the world and connecting us with its peculiar wonders and horrors. In this dual sense, it is the closest thing to love. We read to transcend the confines of our own minds, and books are ideal for this because they combat distraction, brevity, and spectacularity, enclosing us in their modest pages like an oyster cradles a pearl.

However, we are going to replace books with more entertaining “other formats” to satisfy the interests of unscrupulous magnates who seek to draw children onto social media as early as possible. For their First Communion gift, or by the age of eight, we will give children devices that encourage inattention.

A country with more capable, critical, creative, and free individuals is undoubtedly a better country. However, such a nation is also likely less accommodating to magnates, thieves, and the powerful; and therein lies the crux of the matter.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons