- HumanitiesLiterature

- 14 de June de 2024

- No Comment

- 19 minutes read

Vicente Luis Mora: “We want to believe that we can truly shape reality with words”

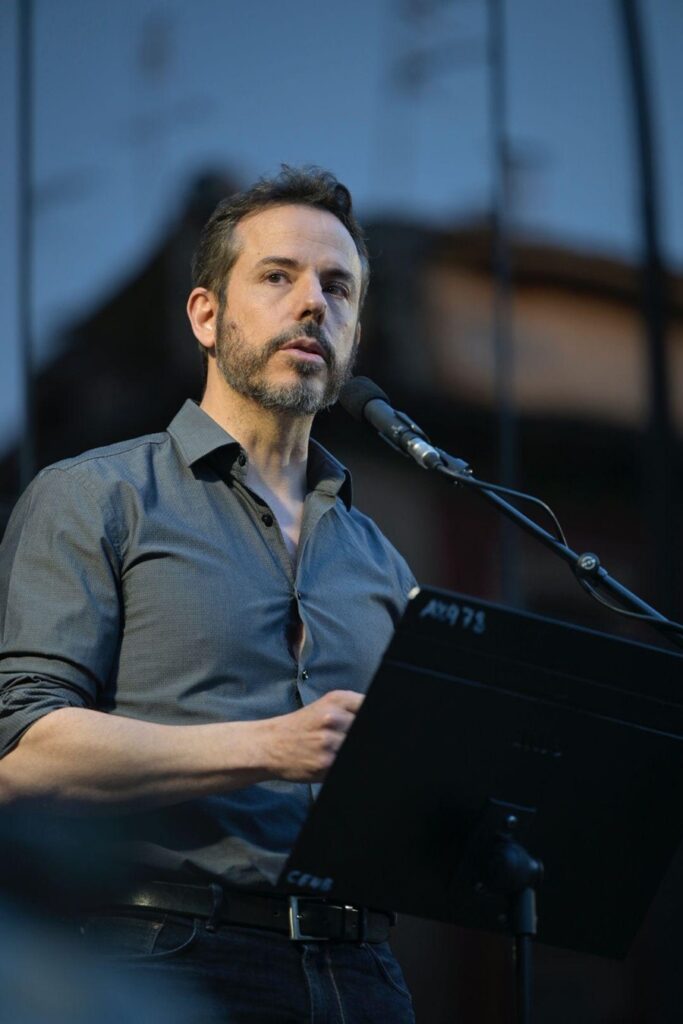

Interview with Vicente Luis Mora: Novelist and Researcher – A Complete Writer

Vicente Luis Mora: “We want to believe that we can truly shape reality with words”

Vicente Luis Mora (Córdoba, 1970) is a stellar writer and one of the country’s most prestigious philologists. In this interview, he not only reviews his literary career but also his academic journey. This man has done it all: poetry, criticism, post-essayism, aphorisms, aesthetic thought, and several important novels. With Cúbit (Galaxia Gutenberg), he has ventured into dystopian or visionary science fiction; with Raíz nebulosa (Dykinson), co-coordinated with Azucena López Cobo and Amparo Quiles Faz, he offers a panorama of contemporary Hispanic Philology. Those who know him well add that he is also a generous and coherent person.

A standard question. Feel free to hate me: Narrative and AI. What should we know?

This is a typical topic that has more bibliography than interest in the sense that the narrative results produced so far do not justify – at least for the moment – the attention we give them. While I have explored this subject in detail on my blog (https://vicenteluismora.blogspot.com/2023/04/literatura-e-inteligencia-artificial.html), I would like to offer some insights here: If you need to rely on a program to write, whether due to a lack of talent or imagination, why do you want to write? What motivates you to write, and who is your intended audience? Do you not have better things to do than to contribute to the profits of a multinational corporation that exploits the work of countless underpaid cultural workers? If your goal is simply to generate combinations of signs, wouldn’t it be more productive and profitable to engage in activities like lottery combinations? If you are seeking prestige, do you believe that presenting digital rehashes as your own work will earn it? If your aim is financial gain, are you confident that literature is the right path? How does it feel to accept that you may not be valued as an artist and need external creative help? These are tough questions, and while I could continue asking more, they might only add to the discomfort.

“If you are seeking prestige, do you believe that presenting digital rehashes as your own work will earn it?”

How would you summarise your main lines of philological research?

My primary areas of research include contemporary Spanish narrative from an extraterritorial perspective (20th-21st centuries), contemporary Spanish poetry (20th-21st centuries), the creative imagination from a cognitive approach, and the influence of technologies on reading and writing practices. However, I have also explored other subjects, such as neo-rural literature and immigration as a literary phenomenon, for which I am sometimes invited as an expert, despite not considering myself one. Additionally, I have other research interests that I prefer to keep private for now.

Some traditional philologists might consider these lines of research too numerous and diverse. Perhaps they are. However, I am not strictly a philologist; my studies span law, art, philosophy, science, and literature, and I believe that the oxygenation my various knowledge brings to literary analysis generates perspectives and ideas that pure philology cannot reach. So here we are, comfortably between impostor syndrome and occasional discovery.

What is poetic “cratilism”?

In simple terms, poetic “cratilism” is a form of literary fetishism that upholds the ontological identity between a word and the thing it names. This means that certain texts or authors reject the Saussurean notion of the arbitrary nature of signs, instead proposing a direct and real correspondence between an entity and its name. They believe that merely pronouncing a word can generate effects beyond speech acts, shaping reality itself.

A recent example can be found in Fernando Menéndez’s “Ni el número ni el orden”: “Decir / espliego / y que / se agoste / el tacto / en tanto / recuerdos” (Dilema Publishers 2023, p. 107). This idea, which I call “cratilism,” finds its roots in Plato’s dialogue Cratylus, where Cratylus argues against Hermogenes’ consensualist (Saussurean) position that names are circumstantial and vary between languages, while objects and beings do not.

The most famous cratilist expression in our language might be Jorge Luis Borges’ line from his poem “The Golem”:

Si (como afirma el griego en el Cratilo)

el nombre es arquetipo de la cosa

en las letras de ‘rosa’ está la rosa

y todo el Nilo en la palabra ‘Nilo’.3

While it is a poetic license and a conceptual game, I have found many instances of this belief in our literature and in the works of talented and esteemed poets, including some canonical names. Why does something so counterintuitive remain relevant? I think because it reflects our confidence in language as a thaumaturgical skill; because we want to believe that we can truly shape reality with words. Though it is false, in the hands of skilled poets, it remains beautiful.

“We want to believe that we can truly shape reality with words. Though it is false, in the hands of skilled poets, it remains beautiful”

What can we find in Raíz Nebulosa?

Raíz nebulosa. Una mirada a la Filología Hispánica is a collection of works generated by the Spanish Literature Department at the University of Málaga that do not share a common theme but do share a coincident theoretical space. There are studies ranging from the Golden Age to 21st-century literature – the latter is covered in my chapter and Rafael Malpartida’s. The reason Azucena López Cobo, Amparo Quiles, and I wanted to do it this way, as coordinators of the book, is because collective monographs are rarely read in one go; instead, each reader selects their preferences. Nowadays, bibliographic searches are conducted digitally and through specialised repositories where digital access is possible in a fragmented manner. Thinking that a thematic monograph will interest the target audience more than any of its chapters individually, simply because all of them address a similar theme, limits the understanding of how academic essays are received, as Azucena points out. The volume’s title comes from a quote by María Zambrano, a thinker I know you are interested in: “El poeta se mantiene vigilante entre su sueño originario –la raíz nebulosa– y la claridad que se exige. Claridad exigida por el mismo sueño, que aspira a realizarse por virtud de la palabra poética” (Filosofía y poesía)2.

Is Cervantes a landscape?

He is both a landscape and a workspace. He is what you see through the window when you look out and what lies beneath the sheet on which you write. He is the substrate and the environment if you write in Spanish. This does not mean that one should copy Cervantes or imitate him, but I do believe – and I shift to the first person because I do not want to sound prescriptive but to remind myself – that I must keep his lesson in mind. What is the Cervantine lesson? It is a complex lesson with several points: 1) Respecting literary tradition does not require abandoning parody, pastiche, criticism, or irony towards its occasional fruits or models. 2) Know the literature of your time, but do not dialogue with it; rather, use it as raw material to write timeless works that will always belong to any era. 3) Do not take yourself too seriously, especially within your work. 4) Do what interests you without worrying about what others will say. You will receive enough criticism from yourself without concerning yourself with what comes from outside.

What was the best thing you took from your stay in Marrakech?

The knowledge of Arab culture, the affection and immense hospitality of the Moroccans I met, and the close contact over several years with Juan Goytisolo. Quite a lot. Part of my time in Marrakech was tough for personal reasons, but there were other experiences that shaped me.

How is the university in Stockholm?

Well, like any other university but with resources and professionalism that I found almost disconcerting and had only known from the United States. This does not mean that philology, for example, is done better in Sweden than here – a comparison that is otherwise irrelevant as it depends on the rigour and creativity of each scholar individually – but I do believe that students have a better learning experience. Everything there is designed for students to leave with immense knowledge in their subjects. The consideration of each profile goes to the extent that when students earn their doctorates at some Swedish universities, the thesis director creates an individual programme for each, with private classes where a world expert meets via videoconference with the doctoral candidate for two or three hours to discuss bibliography, methodology, work organisation, etc. The expert is paid for that session – I know because I have done them – and the university covers the cost.

“Stockholm University has one of the most practical and beautiful libraries in the world where you do not want to work but stay and live”

Now, back to Spain, for example, Málaga: our university has a deficit of nearly thirty million euros, and research funding has been cut to incredible limits. Stockholm University has one of the most practical and beautiful libraries in the world where you do not want to work but stay and live. In my faculty’s library, there is no space for more books, and they do not accept donations. This does not mean I am not happy in Málaga. I am truly happy, and we do what we can to ensure students do not suffer these deficiencies, asking colleagues for favours and performing pedagogical engineering with what we have. But enthusiasm should not be complacent but critical. That a public entity has hired Broncano for 28 million euros but no administration dedicates that same amount to cover my university’s deficit says everything about what is considered important in this country.

Why did you consider your 2003 Poetic Autobiography a “horror novel”?

At that time, it seemed funny to me, and indeed it is a very minor book that I exclude from my poetic bibliography. When you are unpublished or almost unpublished, you make very bad decisions; you have to be careful with the rush to publish, and it played tricks on me. It is a book of fictional poetry, hence the joke of presenting it as an autobiography belonging to the horror genre. The latter is true: Autobiografía is a horrific book, but because it is bad.

What would you recommend to a young Spanish philologist just starting to research?

I would advise doing the opposite of what I did. Follow the guidelines set by evaluation agencies, stay within established boundaries, and avoid getting involved in the literary world. Don’t mix methodologies, keep your research focused, and ensure your lines of work are profitable. Limit your interests to no more than two areas, refrain from creative writing and literary criticism, and concentrate on a few key topics. Avoid reading about subjects that aren’t considered profitable. By adhering to these recommendations, they will likely achieve significant success. This is what ANECA1 expects them to do.

That said, it is very likely that what that student writes will not interest me much; the more deviation from ANECA a text shows, the greater its theoretical interest.

Tell us how Circular 22 came about.

In 1994, during a trip I took to Madrid for a competitive exam that I failed, I boarded a bus to return to a relative’s house. Failed and now relaxed, I watched the metropolis (for someone from Córdoba, Madrid was then a megalopolis like Shanghai now), and suddenly I wondered if I could write the city, the entire city, street by street, square by square, inventing characters and plots for each. That is when the entire book struck me at once in my head. The epiphany was brutal, but I realised that at that time, I had no time to do it – I had to keep preparing for exams – and that I needed to improve as a writer to tackle the project without ruining it. Over the next three years, in my spare time, I read all the experimental authors I could, both Spanish, Latin American, and foreign, and I studied literary theory, aesthetics, scientific, architectural, and urbanistic theories because what I intended to create was a city. In October 1997, I bought a pack of medium-sized cards, slightly smaller than a quarto, and began to write. In its first configuration, which governed the publications in 2003 (Plurabelle Publishers) and 2007 (Berenice), Madrid was the universe of the book, but from 2008, I began to make it more universal, and Madrid became the centre but an increasingly smaller centre. With Circular 22, I have closed the project after twenty-five years of fairly continuous writing. When I envisioned it, I told myself it would be a book I would write throughout my life, but over time, I discovered that twenty-five years is a lifetime, and I prefer Circular 22 to have reasonable dimensions and above all, a tension in writing that would be lost if I dedicated myself to expanding it instead of making it grow.

Which Spanish authors interest you lately?

Among the living, I follow with special attention the narrative of Begoña Méndez, Rubén Martín Giráldez, Raquel Taranilla, Mario Cuenca, Andrés Ibáñez, Cristina Morales, Javier Moreno, Belén Gopegui, Gonzalo Torné, Pilar Adón, Luis Rodríguez, Aixa de la Cruz, and Borja Bagunyà. This does not mean they are the best but that they are among the most interesting to me due to their risk-taking, responding to your question. If the question were about the most outstanding voices, it would be a tricky issue for which I would charge money (no joke) because it would take years to answer. In poetry, I am interested in the twenty-two authors I included in La cuarta persona del plural, and I read with attention Chantal Maillard, Olvido García Valdés, Antonio Gamoneda, Juan Carlos Mestre, Olga Novo, Ángel Cerviño, Miguel Casado, Clara Janés, Miren Agur Meabe, Juana Castro, Concha García, Miriam Reyes, Berta García Faet, Ángela Segovia, David Leo García, Dafne Benjumea, Olalla Castro, Nieves Chillón, Isabel Pérez Montalbán, Esther Ramón, Luz Pichel, Chus Pato, Virginia Aguilar Bautista, Ruth Llana, Lucía Boscá, Lola Nieto, Blanca Llum Vidal, among other notable voices that I review on my blog. I miss Eduardo García and Marta Agudo greatly. Yes, there are many women on this list. I believe women are surpassing men in the 21st century. They are bolder both semantically and formally; they are staling our thunder, as we say here.

Who was Alba Cromm?

The protagonist of my second novel, the narrative work I am least satisfied with. I always experiment and push books to the limit, and that continuous risk implies that you will occasionally make mistakes. It is not that Alba Cromm is a failure, but it has flaws. I have no interest in reissuing it. I would have to rewrite it thoroughly, and its world feels increasingly distant, probably because it is our own. The future of that dystopia is this present, the one right now. Nautilus, the artificial intelligence I described in 2010 in Alba Cromm, has the same characteristics as Chat GPT-4.

Are you in love with Cúbit?

Beware of Cúbit, it is not as good as it seems. Alcio supposedly kidnaps and flees with her to save her from the experiments her government will subject her to, but then she is the one who experiments with Alcio… And that is just the beginning. To write Cúbit, I was clear that the novel required the three species (the itria, the human, and the IAR) to truly fight for their survival against each other. Benevolent readings of the work – and of the character Cúbit – are not well-directed.

What are you writing now?

Now I am only writing academic articles. In the summer, if I can, I will start the draft of a novel I have been thinking about and taking notes on for three years. I planned to write it last summer, but it was not ready – or I was not. Now my head is literally buzzing with ideas, and I need to get them out and put them in writing. I have never been more eager to write.

Will there be a Circular 50?

Phew! I don’t think so; my mind is on other projects, and I have long managed to disconnect from the type of attention the book requires. The only factor that could distort my plans to leave the project behind would be if Circular 22 were translated into other languages, in which case I would have to immerse myself in its world again to ensure a good translation. And there I cannot answer; the book is an octopus whose tentacles it would be very easy to fall into again. In any case, whatever happens, it will always be there because I consider it the nuclear centre of my literature.

———————–

1 ANECA (National Agency for Quality Assessment and Accreditation of Spain) is a public entity responsible for the evaluation, certification, and accreditation of the Spanish higher education system.

2“The poet remains vigilant between his original dream – the nebulous root – and the clarity demanded. Clarity demanded by the dream itself, which aspires to be realised by virtue of the poetic word” (Philosophy and Poetry).

3“If (as the Greek affirms in the Cratylus) / the name is the archetype of the thing, / in the letters of ‘rose’ is the rose / and all the Nile in the word ‘Nile’”.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons