- HumanitiesLiterature

- 3 de September de 2024

- No Comment

- 32 minutes read

“Today we have only one thing: economic success at any price or failure”

Interview with José Luis Villacañas Berlanga, essayist and tireless teacher

“Today we have only one thing: economic success at any price or failure”

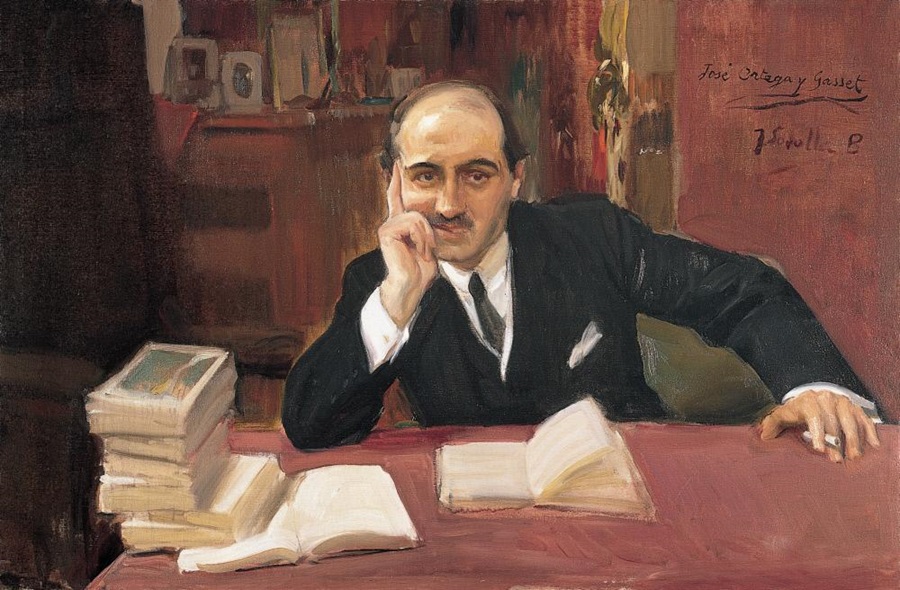

We were not yet recovered from his monumental Ortega y Gasset: una experiencia filosófica española (Guillermo Escolar Editor) and José Luis Villacañas Berlanga, a great philosopher and an outstanding historiographer as well, professor of History of Spanish Philosophy at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, strikes back again with more and more new works, not giving us a break. In addition, besides being a magnificent essayist, he’s a calm and serene voice of a certain left that is becoming increasingly necessary. He has just published Max Weber en contexto (Herder, 2024) –Max Weber in context-.

Let’s start, if you don’t mind, at the end: Max Weber. What are we going to find out in this recent book?

First of all, a philosophical approach to the figure of Max Weber. As is well known, Weber is an outstanding figure in the social science. However, his idea of science and the context in which he worked were very concrete and must be reconstructed in order to understand it properly. That’s why my book is entitled Max Weber in context. The mature Max Weber became a member of the neo-Kantian tradition of the Heidelberg School, founded by Windelband and with Heinrich Rickert as its main philosopher. According to this tradition, science had to be based on philosophical principles that make it possible, in the kantian sense. However, Weber came from other intellectual environments – mainly from the influence of the Historical School of National Economy – which included a kind of vague Hegelian influence, as well as important romantic, nationalist and some Nietzschean tendencies.

When Weber experienced his profound psychic crisis, he came to break with the intellectual cosmos of his teachers, the current environmental Hegelianism, and he aspired to provide the social sciences with a philosophical self-understanding. This led him to exhausting polemics, in which he became involved with a pathos full of drama and sincerity. Thus we can say that he critically constructed a new idea of social science as a science of the human, capable of adequately integrating history and social theory, around a theory of culture centered on the historical effects of human types. In this sense, he left no stone unturned. He broke with the Historical School of Roscher, Knies, Schmoller; he opposed the theory of history by Eduard Meyer, criticized Stammler, and later entered into an important conversation with the Vienna School of Theoretical Economics and of course with Simmel.

“Weber developed the memory of the human as a condition for exercising responsibility”

In the end, he aspired to put into practice an idea of social science capable of simultaneously surpassing the two authors he most respected and seemed to him to be the most important of the present, Nietzsche and Marx. In contrast to them, he asserted an idea of science and of the human being, of society and of history, which has its central inspiration in Kant, and that is why the subtitle of the work is “Philosophy and social science following the path of Kant.” The key to his Kantianism consisted in denying the intrinsic rationality of reality and, in the face of its always anti-human nature, he defended that the dignity and honour of the human being resides in acting freely in the face of this irrationality and assuming the inevitable negative consequences of this freedom through a sense of responsibility. In order to weave this ethical dimension without bad or false conscience, without ideological alibis, without bad faith, without self-deception and without being dominated by unconscious elements, he identified the function of the social sciences in offering us a critical reflection on the logical structure of our values, turning them out as rational as possible by describing the historical experience that they had shaped. From this point of view, Weber developed the memory of the human as a condition for exercising responsibility.

You’ve also recently published Giorgio Agamben. Justicia viva (Trotta) –Giorgio Agaben. Living Justice (Tr)-. What stands out about this living classic?

Agamben has become a central reference of radical contemporary thought, and this is due to the fact that he has been able to offer what we could call a concept of the spirit of the times. We will hardly find a relevant thinker of contemporaneity who does not have his place in Agamben’s thinking. In this sense, he has been able to offer us a systematization of contemporary thought in which, from Carl Schmitt to Hannah Arendt, from Heidegger to Benjamin, from Adorno to Pasolini, from Foucault to Debord, from Benveniste to Deleuze, from Aby Warburg to Overbeck, everyone has their place. Along with this, Agamben has been able to provide philosophical relevance to a whole series of thinkers, scientists and writers of another level, but who play a very central role in his thought process. The result is an impressive work, which is able to x-ray the central elements of the contemporary world and to show the absence of walls that could stop the barbarism we are heading towards.

“The most terrible thing about our situation is that all the evidence supports Agamben’s surrender to the heroic, almost quixotic character of Weber”

Faced with this horizon, dominated by the political theology of capitalism, which produces a global petty bourgeoisie characterized by what I call “voluntary ignorance” as the last historical form of “voluntary servitude,” lacking language and a way of life, Agamben proposes that we reconquer the human capacity to think the impossible, which he identifies with the human capacity to reconcile oneself with one’s own posthistorical animality. In this sense, Agamben constitutes an anti-Weber. While Weber designs a theory of science intended, in Kantian terms, to propose a praxis and a responsibility, Agamben already lives in the contemporary world specifically shaped by financial capitalism, based on the exploitation of information and virtuality, on the projection of the human psyche into intelligent machines and, therefore, on the opening of a human life reconciled with the animal form as the only way to escape exploitation.

Weber did not give up on the human. Agamben places himself in the situation in which the only way to recover it is to overcome the anthropological difference. Denying objectives, praxis, aspirations, temporality and history. Because all this will only give capital alibis to continue imposing its logic, which sooner or later will involve setting up new concentration camps as defensive institutions for those who administer it. The most terrible thing about our situation is that all the evidence supports Agamben’s surrender to Weber’s heroic, almost quixotic character.

Obligatory question: what is your general opinion of Ortega’s thought?

Summarizing more than a thousand pages written about Ortega would be an additional pretension to the fact of having written them. Whatever my general opinion of Ortega’s thought may be, I believe in the need to confront and understand his thought in order to prevent Adamism and presumed genius, something that is a permanent inclination among us. I have read Ortega for as long as I can remember and I have been explaining him year after year for more than thirty years so far. In doing so, I wanted to achieve something: to bring Ortega down from the pedestal of the definitive Spanish philosopher, in order to give him life. Ortega is sometimes like the Prado Museum, a State philosopher, who must be visited from time to time. People go to it because one cannot be Spanish, and a cultured Spaniard, without mentioning Ortega. And in a certain way it is natural. In addition, he has a Foundation that promotes his study and that has an undeniable prestige, but at the same time offers him a certain official status. What is usually promoted in this way is Ortega explained by Ortega himself.

My approach has another purpose and aims to avoid self-referentiality. To do so, I wanted to approach Ortega by addressing the problems he addressed, but from what we can say we know or think in the present. The structure of my book is that Ortega’s problems, in a certain way, continue to be our problems, but his answers are far from being acceptable to the thinkers of my generation. This exercise is worthwhile for several reasons: first, because Ortega is the only Spanish philosopher who has managed to make philosophy part of Spanish culture; second, because he has had a very important influence in the Latin American world; third, because he is the first to do so from the modern way of being both a professional philosopher and a journalist. What I wanted to do in my book is to propose one more effort. To go beyond Ortega, but from the evidence of the simple fact that we cannot stop at his solutions.

“I wanted to think of a living Ortega, asking questions from the present or from other authors that he could not integrate”

The current Spain is not Ortega’s and his world was completely different from ours. We have similar problems, of course, but also different ones, and we even see similar ones in a different way. We need to think about life, as he insisted so much. But we cannot stop going to the other thinkers of life in the 20th century, from Plessner to Agamben and the new scientific understandings. We need to think about history, as he wanted. But we cannot do it without Weber. We need to think about what historical concepts are, but not without going to the work of Koselleck. We need to think about the theory of metaphor, but not without the work of Blumenberg. We need to think about technology, but not without the current reflections on AI. We need to pursue Ortega’s problems, but we cannot convert Spanish philosophy into a quotation or a celebration, but rather into a duty and an aim open to future. I have wanted to think of a living Ortega, asking questions from the present or from other authors that he could not integrate. It is not an infallible Ortega who emerges from all this, but does philosophy may ever afford itself to be done without criticism? It is necessary to highlight both Ortega’s weaknesses and his brilliant successes. This is necessary, especially when he thinks about Spain, Europe, democracy, America or the United States.

What exactly is Neoliberalism? Why is it such a dangerous civil religion, why is it not Liberalism?

In my opinion, the first thing we must ask ourselves is whether our categories are adequate to describe the world of the present. We speak of liberalism, one of the great options of classical humanity; or of neoliberalism, invoking relevant intellectual figures, such as Hayek, Eucken, Röpke, Rüstow, etc. We feel pleased to cite Foucault again and again as the first to identify that the ontology of the present is neoliberalism. I myself have written about neoliberalism as a political theology. But I now have a slightly different position. I think we are dominated by a perception of the world that has the structure of political theology, but I don’t think it can be described as neoliberalism.

“I think if the great neoliberal authors were to raise their heads, they would not feel very recognized in the present”

I think if the great neoliberal authors were to raise their heads, they would not feel themselves very recognized in the present. In my opinion, they had a high opinion of their own intellectual position and I don’t think they’d feel identified with the barbarism that is currenmtly running on. Sobriety, the alleged intellectual rigor, the capacity for analysis, their academic legitimacy, seeing themselves like the defenders of the best European intellectual traditions, all of this as genuine characters of neoliberalism… And those are not precisely the current prevailing attitudes and principles in the present form of domination. The intimate conviction that they were defending positions based on a theory of reason… all of that has been abandoned.

Today we have only one thing: economic success at any price or failure. Everything else consists of eroding the retaining walls so that the only relevant thing left standing is economic success or failure, with ruthless treatment of those left behind. But of course, that includes orienting the economy from a political programming and from power, so in fact only those who already have success can be successful. That is: it is about orienting the economy towards accelerated and concentrated capital accumulation, whose counterpart are the massive processes of general poverty production. This political orientation of the economy towards the concentration of capital, which implies increasing monopolies, is contrary to Hayek’s neoliberal thesis, obviously. It is true that for them competition was the fundamental law and this implies virtue and flexibility, but they assumed that competition should occur under non-monopoly conditions. In their theory of money, they assumed that no currency could be dominant, which makes their world the world of yesterday. They were globalists, but not defenders of imperial powers, which was completely naive. But in a certain way they believed in reason.

In short, the bare form of domination we are subjected has no serious theoretical support. It is bare domination and that induces them to seek hypocritically for theoretical authorities. If Hayek were alive he would spit on Milei and Trump. There is no theoretical dignity in the domination we suffer. But it is a theological-political violence, because it governs minds and bodies, ways of life, desires, subjectivities, in order to prevent any alternative, reifying history from a supposed final stage of humanity and so petrifying social relations. And that is theological despite the fact that there is no single imperial power behind it. But it is the way all world powers operate. That is why they are so selectively akin to the forms of religious fundamentalism, as seen in the strange alliances involving Trump, Putin, the ultra-orthodox of Israel or Arabia.

What is going on in Europe? Will we be able to overcome this obstacle?

Europe has already spent its imperial history and cannot compete with the imperial powers that are fighting for the world. It is a subordinate power, which rather hinders than helps the future world battle. Or at least that is what it is being told: do you help or hinder the upcoming struggles? Because the struggles will exist, or at least the struggles to achieve the best coercive conditions in the future. These struggles have a name: Asia. That is what counts.

South America is abandoned, and that’s a very serious mistake, because the only real place for democracies is Euroamerica – by the way, a word that appears in Ortega’s. For some time now, however, Europe has been more of a burden for the battle of Asia. It was when it denounced the war in Iraq, which intended to move the Berlin Wall to Baghdad. It has been in Afghanistan, with its demands for compliance with human rights. But the future is more concrete. This is about Iran. We wonder why the United States supports Israel unconditionally. It does so for Iran. Gaza is the beginning of the war with Iran. Then comes Lebanon and then Iran. Because it is essential to have one foot in the navel of Asia. It was tried in Afghanistan, but it failed because nothing can be built on the barbarity of the Taliban. Moreover, we need a people who are one of the pillars of the Earth. Not even Pakistan is. But with Iran there is no doubt. It is older than all of us. The Iranian culture is an ancient one and, what is more significant, deeply related to the West, much more than the Abbasid culture. When the Ayatollah’s stop ruling there, it will be the only Islamic place where democracy is culturally viable. That is the logic of the world.

“Gaza is the beginning of the war with Iran. Then comes Lebanon and then Iran. Because it is essential to have one foot in the navel of Asia”

Europe can only give a little help: to incorporate Georgia, and of course Ukraine. This will be the key to Trump’s next term: whether Europe alone will be able to sustain the war in Ukraine against Russia. I do not think that Trump can alter the deep logic of the American power structure. In this situation, the European populations do not respond with enthusiasm. They only think about remaining the privileged country on Earth. However, we should realise that, in order to be so, we have to defend democracy, and to do so we must as soon as possible promote a policy of peace and a policy of cooperation with our neighbours in the Middle East and North Africa. The extreme right will not do this, and will try by all means to promote neo-imperial policies. However, I do not think that we Europeans are in a position to offer a majority popular base for these policies.

I think that the extreme right is wrong when it thinks that it can mobilize the European population in favour of these policies when it comes to power. People who vote for the extreme right do so out of fear and hysteria, and their vote is nothing but an expression of weakness and cowardice. We must fight these attitudes because, even if we lose a lot, we will be the privileged place of humanity. We must remember that Europe has always been a land crossed by migrations. What we must prevent is the monopoly of mafias, wich is an informal slave trade. The human volcano is too strong to prevent migratory movements. It is better to know how to cultivate with the lava that it brings us and understand that lava is life.

What is happening to the left today? Why is it sick? What do we do?

The left also lives on the representations of a world that does not exist. It was Weber who said that if the revolution were to triumph in Russia under the cultural and social conditions of that time, it could only be imposed by establishing a disciplinary bureaucracy that would bring a hundred years of discredit to the noble idea of socialism. From this point of view he was more lucid than Marx, who thought that legal titles to the ownership of factories would be sufficient to achieve an emancipated condition for humanity. But it is the productive structure itself that imposes a bureaucratic order that per se is a structure of domination, whoever owns is. But the capitalism that Marx knew and that was imposed in Weber’s time, in the form of industrialization, Fordism, rationalization, massive attention to needs, all that is already very socialized. The great sources of accumulation today are housing, virtual commerce, health care and education, and the great battle is to socialize these goods sufficiently.

“Socialism lived on the idea of revolution, but we have seen that the only thing that has been truly revolutionary has been capitalism”

The noble idea of socialism cannot be imposed except from the noble idea of democracy, and democracy as a process of socialization must use all collective, public, common places to organize all spaces, the larger the better, to contain accumulation as much as possible. That implies something theoretically very relevant. Socialism lived on the idea of revolution, but we have seen that the only thing that has been truly revolutionary has been capitalism. I believe, as Ortega would say, but for different reasons, that we have to reflect on the idea of revolution. If we look at the history of Europe, there have never been constructive revolutions. All of them have faced situations of extreme oppression that legitimizes them, but they have not managed to build novel situations in the long term. The idea of revolution responds to an urgent situation that is only credible from extreme oppression and tyranny. The ruling classes know that they cannot produce this and now they give us a reduced, minimal, brutal freedom that neutralizes any revolutionary condition. We must think differently. We need retaining walls to protect the worlds of life that are not yet crossed by accumulation. The public must be defended with the firm conviction that it is the main one of these walls. That is why those who misappropriate and discredit it are so guilty. That is the ally of domination. Its agent.

What do you think of Habermas and Lledó?

I have read a lot of Habermas. When I founded Daímon, one of the best philosophy journals, I devoted the first issue to him. I have followed his work with some attention and have observed his evolution with interest. This evolution is a mixture of a better understanding of many problems and authors – for example Weber or Koselleck – and an abandonment of maximalist positions of youth. But in general, Habermas has not taken French thought seriously, which is fundamental for our contemporary world, nor has he been able to criticize it with solvency. The times he has done so, he has shown limitations and improvisations. I think that Habermas’ problem is his Hegelian origin, which has a community and consensual background that complicates the democratic idea. For my part, I believe that democracy has no material consensual background. Democracy is the way of pushing for equality in human life, which always aspires to inequality. Democracy is polemical and that is the republican principle. It arises from inequality and aspirations for equality, and that is why it is the way in which unequals must become strong in order to redistribute power, wealth, honour and distinction. Democracy is struggle and intelligence. That is why it disappears if we succeed in inducing populations towards voluntary ignorance. That is the aspiration of all political theology: to make us worship those who dominate us. There are very refined techniques for this. And philosophy is one of the most effective ways to oppose them.

“Democracy is struggle and intelligence. That is why it disappears if populations are induced to voluntary ignorance”

Regarding Lledó, I must say that we are very good friends, that he has always helped me in my career and that he has been a model of clean living, both in his family and professional life, for many of us. It is a great merit that he has survived the Franco era in which he grew up with intact dignity and that he has become an exemplary citizen in our democracy. It is important to remember that, despite having suffered the most shady and sordid aspects of academic life, he has never stopped being a great philosopher, studying and thinking in a way that always has inspired us. He has been, and he’s yet an example of intellectual and personal integrity for all of us.

“Our intellectual culture is a tradition of wit and brilliance, and it is so until Unamuno, Ortega and Zambrano”; this phrase comes from your prologue to Baltasar Gracián: filósofo de la vida humana, de Borja García Ferrer. Could you elaborate on this?

Yes, our philosophical culture is largely literary, as well as a literature of brilliance and wit, that is, literature as understood by Baroque culture. The countries of southern Europe tend to believe that Baroque is a general European culture. I think otherwise. In the north there is no culture of pessimism, of death, no miracle of a concentrated light. That is the consequence of the different way to understand the Spirit in each culture. In the south, the Spirit is concentrated in the Pope. That leaves the others in melancholy. In the north, the Spirit spreads through everyone and produces the firm conviction of the reformed, always prone to enthusiasm. In parallel, the southern Baroque culture moves around elitist mental structures, and lives off the metaphor of the dark character of life on earth, only sometimes miraculously illuminated by the representative of the Spirit, who radiates light and enables to see with a certain distinction what would otherwise be nothing but confusion and chaos. Of course, the matrix of this metaphor is that of Corpus Christi itself, which, enclosed in its impressive golden monstrances, walks through the city illuminating the lives of people, people generally condemned to poverty and suffering because the accumulation that gold and silver on altars and sacred vestments promotes. This light, which comes from transcendence, always ends up finding secondary sources in immanence. These are our baroque authors. And that is the function of their brilliance and wit.

But in the same way that transcendence tends towards monotheism, these new lights strive to be unique, superior, supreme. That is the aristocratic nature of all baroque. Only perhaps in Hispanic America was the baroque something else since being conveyed through Indian culture, its crafts, its styles, its popular cultures. In fact, many ornaments and motifs of the baroque are Amerindian. This popular American baroque art continues to move us with its touch, color, naivety. But in Spain it was not like that. Literary culture was the ruthless struggle between diminished elites, forced to play on a very limited terrain, which never really touched the power structure. There is only one exception for me, where the rationality of the time was concentrated, but it was that of a brilliant man who really paid for being brilliant. I am referring to Saavedra Fajardo, the reason for the Hispanic Monarchy of the first half of the 17th century. Ortega comes from that tradition; Unamuno criticized it as a traditional culture, but in the end he shared many things with it, like his fondness for paradox and semantic invention. Zambrano, by proposing what she calls poetic reason, is nothing else than just to intensifie the style of Ortega, who’s the living expression of literary mannerism.

Only Zubiri is the exception, but I am not sure about him, because his impenetrable conceptualism also has a lot of baroque. A clean style, which seeks authentic clarity, which pursues the problem to the bottom to short-circuit the alibis of ambiguity, the honesty of reflective intellectual work that the more it reflects, the more clearly it expresses the result; that is what we have lacked. I am not thinking of Alfonso Reyes, although somehow I do. He writes as if he were painting, and you have to read him like watching at a painting. But sometimes you have to make the painting less superficial and use the foreshortenings. Philosophy must let you see the layers of the problem, but it must teach you to go through them in an orderly manner. This requires an effort and a work that goes beyond brilliance and ingenuity. It is the intellectual work that never gives up the aim of improving, but it’s leaving behind traces of clarity.

Which of our Renaissance and Baroque thinkers have we ignored until recently?

We have ignored almost everything about our thinkers. In fact, in Spain there has been a desire to produce ignorance as a part of the historical domination that we have suffered. It is monstrous to notice that for centuries we have not been able to write freely about such an important event as the Reformation. Until the advent of democracy there has been no single book dedicated to Luther in Spain. Not to mention Calvin. Our Sephardic past has been ignored and has had to be conquered fragment by fragment.

Our critical thinkers have started almost from scratch in each generation, and they had to reconstruct their background with a great effort meanwhile they were often accused to be producing inventions. Many fundamental books were in fact unknown until quite recently. In the midst of Franco’s regime, five centuries after it had been written, it was published the most important book of Sephardic convert culture, Defensorium Unitatis Fidei Christianae, by Alfonso de Cartagena… in Latin. Nobody was able to read it. There is not that long since we’ve had an adequate scientific version. The Socorro de los pobres by Luis Vives, an outstanding talent of the European 16th century, had been translated in 1528, but to be put in the drawer of the inquisitor of Valencia. We published it in the Valencian Library in 2001. When Palacio y Palacio found the Inquisiton trial to Vives’ mother and family, which showed that he was Jewish, he had to endure innumerable pressures and finally deleted the part referred to the father. I am committed to the reconstruction of critical convert culture, generation after generation, whom opposed the traditional culture time, generation after generation. And this implies a new canon and a re-evaluation of the current one. It all really began with Slomo Ha Levi, known as Pablo de Cartagena. From there to Spinoza, almost in the 18th century, there is a whole tradition that transfers points of view, attitudes, rhetorical forms, sources, antecedents. When we get this critical tradition finally fully reconstructed, the conventional canon will be reinterpreted in its grandeur. There is a lot of secondary research on all of them. It is not yet offered to readers in an organized, systematized, ordered manner, with the appropriate significance of relationships. It is the work of several lifetimes.

“I am a Kantian in what concerns to the normative – and therefore a republican – influenced by Weber in the knowledge of reality – and that is why I try to provide the State with controlled but effective powers”

Do you have magic powers? Do you rest from time to time?

Of course, my life is quite orderly and normal. I rest like anyone else and I have an intense family life. I’m married with María José de Castro since 1977, we have two children, Luis and Carmen, who are good people and magnificent professionals, and we have three grandchildren whom I love to play and chat with. I have no magic! I am completely against anything that depends on chance. Methodical and regular work is very productive. I just feel the passion for knowledge, which, by the way, as Nietzsche said, is a rather plebeian passion, typical of someone who is the first university student in his family, as if centuries-old hunger for knowledge were nesting in me. It’s true. I have always learned by all means. And I still do it. I live learning. I don’t rest from this. That hunger runs through my unconscious. I dream that I write, my dreams of writing things are constant and when I get up I remember them.

Do you consider yourself a neo-enlightened person? How would you define yourself?

I am a Kantian in whats concernig the normative – and therefore a republican – crossed by Weber in the knowledge of reality – and that is why I try to endow the State with controlled but effective powers; quite Machado-like and Nerudian in the poetic, and Freudian in the understanding of the psychic apparatus and the anthropological condition. Of course, I’m a reader of San Juan de la Cruz when devoted to the oceanic feeling of reality, but in other respects I am something like a cultural Lamarckian. I believe that the original experiences that configure the generativity of human life, the structure of filiation, shape in a quite intense sens our way of looking at the world. My hunger for knowledge was already that of my father. And my joy of living that of my mother. The awareness of being well born is quite an important thing in life. To ensure that this awareness rolls is the first obligation of the human being, to extend self-confidence among those whom we brought into the world without their consent. That is the only shield against hatred and certainly the source of productive energy.

A book urgently to be read today…

If there were only one, humanity would be saved. Unfortunately, this is not the case. But if one had to be chosen, in this current circumstances, I’d recommend The Dual State by Ernst Fränkel. It is a story that reminds us how Nazism could be acceptable to millions of educated and well-intentioned people. It has to do with the pacts between political power and judicial power. We should pay attention to this genealogy of totalitarianism, which is more effective and decisive than large rallies, truncheons, ricin and gang violence.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons