- Opinion

- 11 de February de 2026

- No Comment

- 7 minutes read

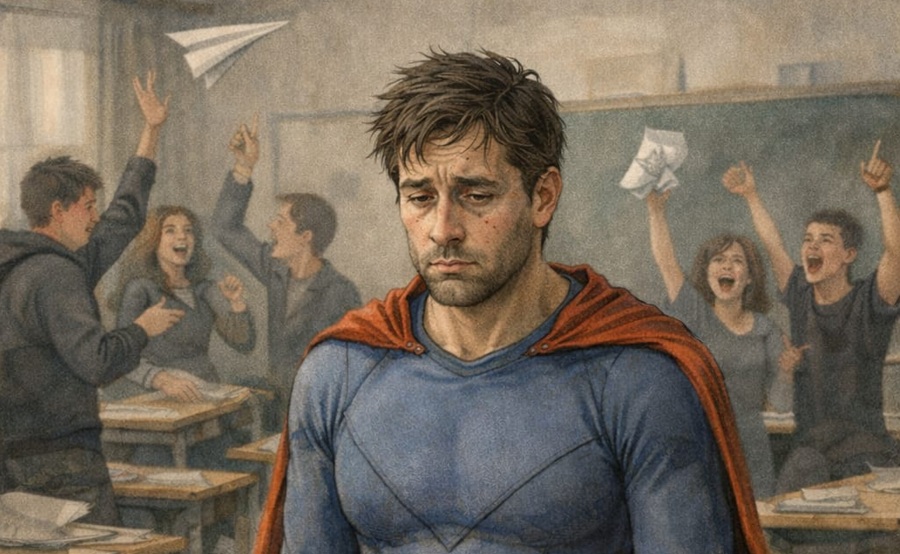

The super-teachers

AI created image

Who has never, at some point, dreamt of having superpowers? To fly, to be invisible, to possess extraordinary strength, to read other people’s minds, to teleport… It is obvious that the American superheroes of Marvel and DC, born in the twentieth century, turned these impossible dreams into enduring icons that still shape popular culture today: Superman, Batman, Spider-Man, Wonder Woman, the X-Men — a whole cast of extraordinary, flawless figures, always ready to fight evil and save the day.

These caped and masked heroes are not, however, a modern invention. The mythologist and scholar of comparative narrative Joseph Campbell describes in The Hero with a Thousand Faces the universal myth of the hero: someone who leaves the ordinary world, undergoes extraordinary trials, defeats formidable forces, and returns transformed to offer a gift to the community. It is a powerful narrative structure, universal, repeated endlessly throughout history in myths, legends, comics, and films. The problem begins when this heroic narrative ceases to be fiction and settles into real professions, such as teaching.

The teaching profession has changed profoundly in recent years. It is a now wldly acknokledged that it has been devalued, both economically and socially. We are no longer a profession widely respected or admired by society—and even less so recognised by our pupils—and our tasks have multiplied to such an extent that, nowadays, the thing we do least is precisely what we were trained to do: teach.

Yet many of us still struggle to acknowledge that something is seriously amiss in public education, and we have, often unconsciously, fallen into a kind of superhero complex. Like Spider-Man, we assume that every pupil’s failure is ultimately our responsibility: ‘if they are not succeeding, I must not be doing enough’. Like Superman, we project constant resilience even when the system subjects us to impossible conditions: classrooms without proper ventilation or heating, unreliable technology, rooms far too small to manage a group effectively. Like Wonder Woman, we contribute our own resources—time, energy, money—and normalise self-exploitation as professional commitment. And so, layer by layer, the boundary between work and personal sacrifice gradually dissolves.

This heroic narrative comes at an enormous cost in terms of mental health and wellbeing. Faced with an overloaded, bureaucratised, and under-resourced education system, the discourse of the super-teacher transforms a structural problem into an individual failure: ‘If I cannot manage everything, it must be my fault’. Distress is internalised, complaint is moralised into guilt, and exhaustion is experienced as a personal weakness. How many times have we sat in a departmental meeting, anxiously sharing difficulties with a class or with a struggling pupil, only to sense—between the lines—the unspoken consensus: ‘this is happening because you are not handling it properly?’ And we return home dejected and exhausted, with a new impossible mission: to improve ourselves so that we can become super-teachers.

Let’s be absolutely clear: this teaching heroism is far from abstract; it has very concrete expressions. It translates into hours of work devoted to endless pedagogical bureaucracy: spreadsheets, reports, and individualised comments that consume time with little real impact on learning. It includes the constant adaptation of tests and activities which, without sufficient resources, dilute subject specialisms and hollow out the curriculum. It takes the form of break-time supervision, cover lessons, extra hours, constant availability beyond working hours, and the management of discipline, confrontation, and even aggression in the classroom. All this turns us into heroes without capes, bearing enormous responsibility, often without any financial compensation or professional recognition. Taken together, it constructs a model of the super-teacher that keeps the system afloat through invisible labour and personal compromises.

We must not conflate vocation with profession. Teaching may well be vocational, but it is not a form of priesthood. When vocation is used to justify overload, precariousness, or the assumption of tasks that are not ours, it ceases to be a virtue and becomes a tool of exploitation. The myth of the ‘saviour teacher’ —the one who can ‘change lives’ at any cost—conceals an uncomfortable truth: without decent material conditions and respect for professional expertise, quality education is simply not possible.

Meanwhile, excess is normalised under the language of ‘commitment’. The good teacher is the one who is always there, who endures, who does not complain. A kind of Captain America of the secondary school, loyal to the mission whatever the circumstances. But this everyday heroism has clear consequences: burnout, demotivation, and people leaving the profession; a loss of teacher authority, because those who take on everything end up with no clear boundaries; and, above all, a lack of accountability on the part of the administration, which can continue to demand more without guaranteeing adequate resources or decent conditions.

We do not live in a film and, unfortunately, we cannot save the world with superpowers. Teaching is not an individual epic, but a profession that requires solid structures, fair working conditions, and respect. Our primary task is to teach and to transmit knowledge with rigour and academic standards.

It is time, colleagues, to take off the mask and reclaim who we are: specialist secondary-school teachers, entitled to decent conditions and professional recognition. When we stop behaving like superheroes, the system will no longer be able to sustain itself on invisible sacrifices and, perhaps, something will begin to change. It is time to restore a sense of perspective: no capes, no superpowers—just clear limits and properly guaranteed rights.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons