- Humanities

- 10 de February de 2026

- No Comment

- 8 minutes read

The St Scholastica’s day riot (Oxford)

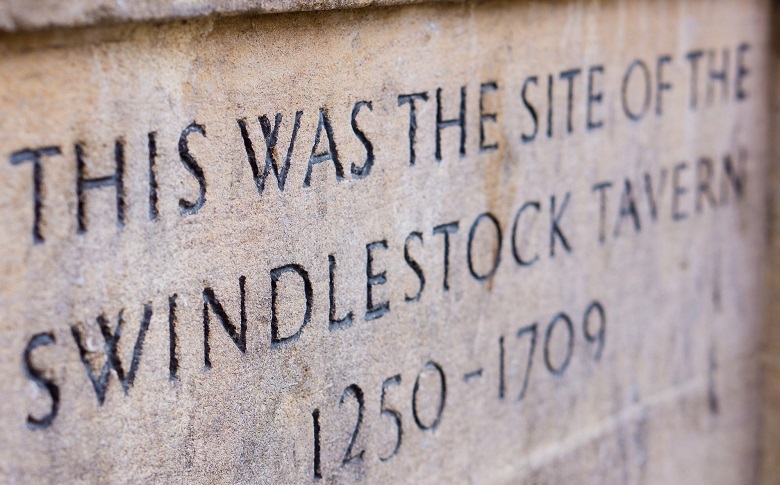

A commemorative plaque on the building that now stands on the site — today a branch of Santander Bank / Source: https://corresponsalenlahistoria.blogspot.com/2016/02/el-motin-de-santa-escolastica.html

The long tradition of student rebellion — and students’ well-known fondness for boisterous drinking and rowdy behaviour — was not exactly invented in Berkeley in the 1960s, nor during the Paris events of May ’68 (the reigning adanism does real damage here). Saint Augustine was already complaining about the fickleness of his students and their tendency towards libertinism — much like his own in his youth, it must be said — but what happened on St Scholastica’s Day in Oxford went much further.

It was 10 February 1355, the feast of St Scholastica, in Oxford, the university town par excellence. Towards dusk, two university students, Walter Spryngeheuse and Roger de Chesterfield, were having a few pints with a group of friends at the Swindlestock Tavern, an establishment frequented by both locals and students. We do not know whether they had planned a classic dine-and-dash, or whether it was simply the amount of beer consumed that sparked the dispute. What we do know is that they became embroiled in a loud and acrimonious argument with the landlord, John Croidon, over the poor quality of the ale — in short, they accused him of watering it down.

The students refused to pay, and in the heat of the argument matters quickly shifted from argumentum logicum to argumentum baculinum: they assaulted the landlord. The locals present took Croidon’s side; the students rallied to their companions. What followed was a full-scale brawl between townspeople and students until the latter, heavily outnumbered, fled back towards the university to seek refuge and reinforcements — without paying, of course.

Hostility between the townspeople of Oxford and the student population was nothing new, and this was far from the first such incident. Since King Henry II had forbidden English students to study in France some century and a half earlier, Oxford University had begun to grow rapidly, with ever-increasing numbers of students arriving in the town. There were what we might call ‘social’ reasons of everyday coexistence behind the tensions. Students looked down on the locals and complained bitterly about extortionate prices. For their part, the townspeople detested the students for their love of hard drinking and their libertine habits, blaming them for their daughters’ unwanted pregnancies and for disturbing the peace with their irrepressible taste for noise and rowdy behaviour.

But there were also more overtly ‘political’ grievances. The civic authorities were keen to assert control over the university and increasingly resentful of its separate legal status, its ecclesiastical privileges and its direct protection by the Crown. On this occasion, however, the mayor of Oxford, John de Bereford, thought he saw an opportunity to exploit popular anger for his own ends. What he achieved instead was to turn what had begun as a drunken tavern brawl into three days of barbarity and open warfare between town and gown.

After the students’ retreat into the university, news of the altercation drew armed townspeople to the area. Several students, unaware of what had happened and venturing near the Swindlestock Tavern, were savagely lynched by enraged mobs. Mayor Bereford then marched to the university with his bailiffs to demand that the chancellor, Humphrey de Cherlton, immediately hand over the two students responsible to the secular authorities. Cherlton refused, arguing that the mayor had no jurisdiction over the university, and dismissed him in no uncertain terms — and with good reason. A few years earlier, two students accused by townspeople of raping a young woman had been handed over by the university and promptly lynched in the street, without trial or evidence of any kind. Whether they were guilty or not was never established, and Cherlton was not prepared to allow such a thing to happen again.

As the mayor and his bailiffs were attacked by students while leaving the university and narrowly escaped, the bells of St Mary’s Church — the university church — rang out to summon the students, who chanted “Havock! Havock! Smyte fast, give gode knocks!” —At the same time, the bells of St Martin’s Church — the parish church of Oxford — were calling the townspeople to arms with exactly the same aim and slogans. By then, several bodies already lay in the streets, most of them students.

That night and over the following two days, Oxford became the battleground of a brutal war, fought with fire and sword, between students and townspeople. The latter even went so far as to storm university buildings and lecture halls. On the third day, royal forces arrived and order was finally restored. Sixty-three students and thirty townspeople had been killed.

Royal justice sided with the university, finding the mayor and the town guilty. King Edward III sentenced the town of Oxford to pay the university an annual fine of sixty-three pence for each student killed. In addition, the mayor and councillors were required every 10 February to attend a mass after processing through the streets bareheaded — a mark of deep humiliation — and to renew annually their oath to respect the university’s privileges.

These ‘penalties’ remained in force until 1825, when the then mayor of Oxford refused to continue taking part in the ceremony. Six hundred years later, on 10 February 1955, the long shadow of the riot was finally laid to rest in an act of reconciliation: the British Parliament repealed Edward III’s decree, the mayor of Oxford received an honorary doctorate from the university, and the City Council presented the university’s chancellor with the keys to the city.

The Swindlestock Tavern remained open until 1709. A commemorative plaque on the building that now stands on the site — today a branch of Santander Bank — recalls its history. The only building from those days that still survives in Oxford today is Carfax Tower, all that remains of the old Church of St Martin.

Whether this custom dates from then — given the uproar, it might well do — is impossible to say. What is certain is that in English pubs drinks are paid for promptly, often at the very moment they are ordered, or even before they are served. And there is, as they say, a reason for that.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons