- Humanities

- 25 de June de 2024

- No Comment

- 9 minutes read

The Pombo Gathering: An Air from Another Time

The Pombo Gathering: An Air from Another Time

Eduardo Alaminos

The writer and journalist Carmen de Burgos, known as Colombine, offered several considerations about the Café de Pombo and the Pombo gathering, which can be viewed on two levels: its physical and emotional reality, and the sociability and significance it held. She dedicated these lines to both the actual Café and the first book that Ramón Gómez de la Serna, with whom she shared life, literature, and journeys, published about it and its gathering, Pombo (1918).

In the newspaper Heraldo de Madrid (January 16, 1916, no. 9,177, p. 3), in the column she wrote under the heading “Femeninas,” she lamented the lack of places that served as “a refuge for women to rest amidst the hustle and bustle of the city with a bit of freedom and distraction […]”. She writes “there is no custom among us for women to spend time in cafés […]; we lack those democratic tea houses that are full in London, where different crowds of the city mix at certain hours […]. We also do not have those cafés in France and Italy, so brilliant and full of freedom, where women enter, leave, read, and write without attracting attention […]. Here, the women who frequent cafés the most are artisan women […]. Women feel that traditional hesitation in us that prevents coexisting with men. At most, they dare to enter some of those discreet, secluded, peaceful cafés that preserve the tradition of their cities”. By “artisan women,” we should understand artists.

The rest of the article focuses more on the physical, human, and emotional reality of Pombo when compared to other European cafés. Those cafés, in the words of George Steiner, defined what Europe was back then—spaces of sociability where one wrote, philosophised, and conversed freely. Of the young people who passed through Pombo, Tomás Borrás emphasizes that they “learned freedom1“. Colombine writes: “Cafés like that old Café Flexing in Bruges, which holds memories of Rubens, and that Café Greco in Rome, the artists’ café that retains its romantic and primitive aspect amidst the modern splendour of the city, and which can only be compared to our admirable Café de Pombo—mysterious and secluded, where it seems there is a hidden treasure, and whose interior depicts a painting by Manet, Cézanne, Degas, or Renoir”.

Colombine’s final words likely inspired Ramón to consider that Pombo—his “mysterious and secluded” café—should also have its own iconic painting, akin to d’Ors’ vitrines filled with memories and anecdotes. This idea followed the tradition set by renowned artists like Manet and Degas, who successfully crafted the modern and psychological iconography of cafés. However, another question arises: why did he choose an artist like José Gutiérrez Solana?

Using the pseudonym “Perico el de los Palotes,” one of the several pseudonyms Colombine used, she published years later in Heraldo de Madrid (July 8, 1918, no. 10,076, p. 2) an article reviewing two of Ramón’s books, Muestrario and Pombo which were released earlier that year.

Regarding the latter, Colombine addresses the significance of that gathering. “Pombo,” she writes, “is a group book, a book full of private and secret stories; but contradicting what could be expected of such a book, it turns out to be a book for everyone, and corrects the idea that art must be filled only with generalities and abstractions. This book, in which a gathering of artists and friends is seen to live more in a human and simple way than in a professional way, has a charm even for those who know nothing about them. […]. In this way, the value of its faithfully reproduced environment—with its trivialities, paradoxes, and even its yawns—becomes remarkable. It is undeniable that this book’s worth will increase over time, even as many names become entirely unknown. Those who no longer recognise the place of the gathering will find in this book the atmosphere of another era […]. The old Café and bottlery of Pombo transforms in this book into a crypt filled with the dense emanations of the spirit of men, of things, of the ineffable, of time, and of the environment, resulting in a warm and evocative place.

Colombine’s two articles essentially reflect the temporality of both the Café de Pombo and the Ramón gathering. The second can almost be considered a complement or response to the extensive and heartfelt portrayal—ethopeya—that Ramón made in Pombo about the writer, a condensed biography that culminated with this expression: “How well Pombo suits her (Especially when she wears Liberty satin)”.

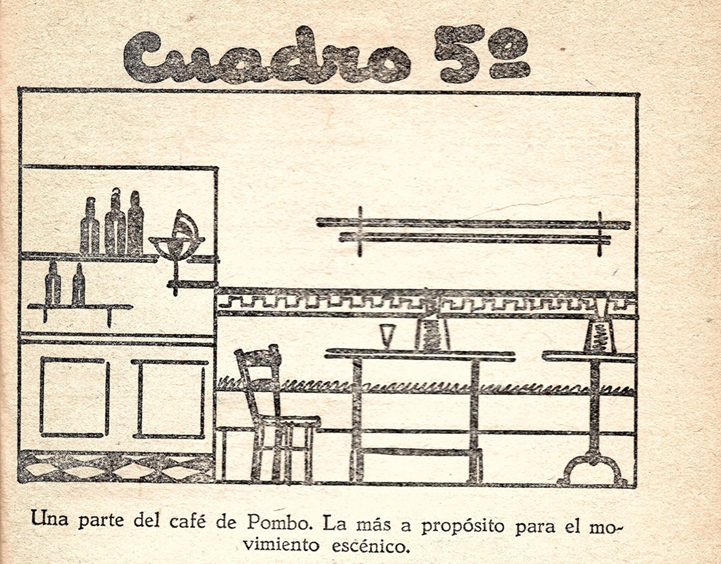

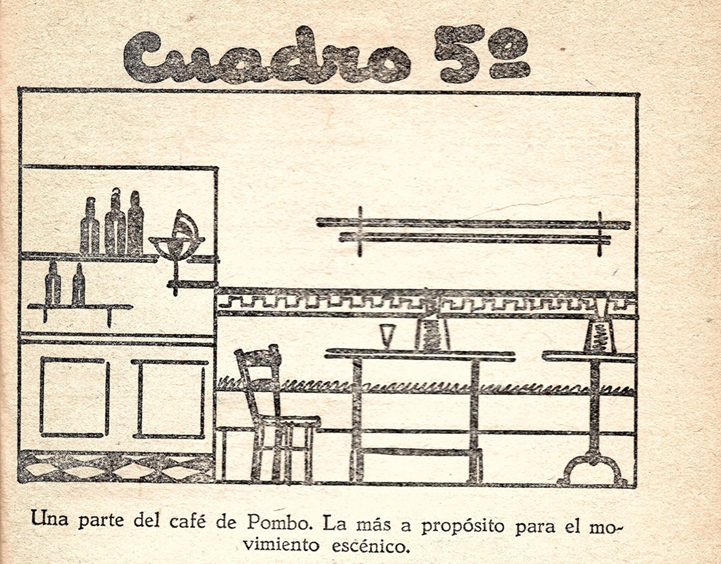

Many years later, on November 8, 1934, Jacinto Benavente premiered Memories of a Madrilenian (in five scenes) at the Teatro Lara in Madrid. This work was published the same year in the weekly magazine La Farsa (Estampa Publishers), illustrated with drawings by Agustín Segura and four photographs of the production. The fifth and final scene opens with a drawing captioned: “A part of the Café de Pombo. The most suitable for stage movement”, followed by the direction for this unique scene: “(A young man and a young woman of health and culture sit at a table. He wears a sleeveless shirt with a jacket over his shoulders. She is very wavy and platinum blonde. He sometimes has his arm around her waist and sometimes on her shoulder. They drink a white coffee. She occasionally offers him a sip from her glass or with the spoon. They are very enamoured throughout the scene as if they were alone in the café. At another table, a young writer with a glass of pure coffee in front of him and a pile of papers, armed with a pen, writes and smokes; he smokes more than he writes […]”.

If we take a “costumbrista” view of those texts by Colombine and Jacinto Benavente or if we contemplate them exclusively from a gender perspective, we first perceive the temporal transformation in that context of sociability mentioned at the beginning and, with nuances, we already notice a change regarding the female presence that the writer so longed for in these spaces, the cafés.

However, we also perceive a change in the representation of the Café de Pombo itself. In contrast to the “naturalistic” iconography provided by Ramón in his first book dedicated to the café, which emphasized its “mysterious and secluded” physicality with drawings by Romero Calvet and Mariano Espinosa, or Solana’s later works, Antonio Segura’s “schematic” depiction introduces a modern abstraction that resembles architectural designs or furniture catalogues of the time. As Ricardo Fernández Romero has noted, it is possible to understand that Benavente, by using the Café de Pombo as a setting, “ironically affirms the resistance of old forms against the new”. Segura’s illustration resolves this contradiction.

___

[1] Ramón Gómez de la Serna. Descubrimiento de Madrid. Edición de Tomás Borrás. Madrid, Ediciones Cátedra, 1992: 16.

[2] Fernández Romero, R. (2012). “Madrid era una fiesta. La escritura autobiográfica de Jacinto Benavente: Memorias de un madrileño (1934) y Recuerdos y olvidos (1959)”. Hecho Teatral, (12), 5-33.

_______

(I) Portraits of a Gathering: Pombo

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons