- Opinion

- 16 de December de 2025

- No Comment

- 7 minutes read

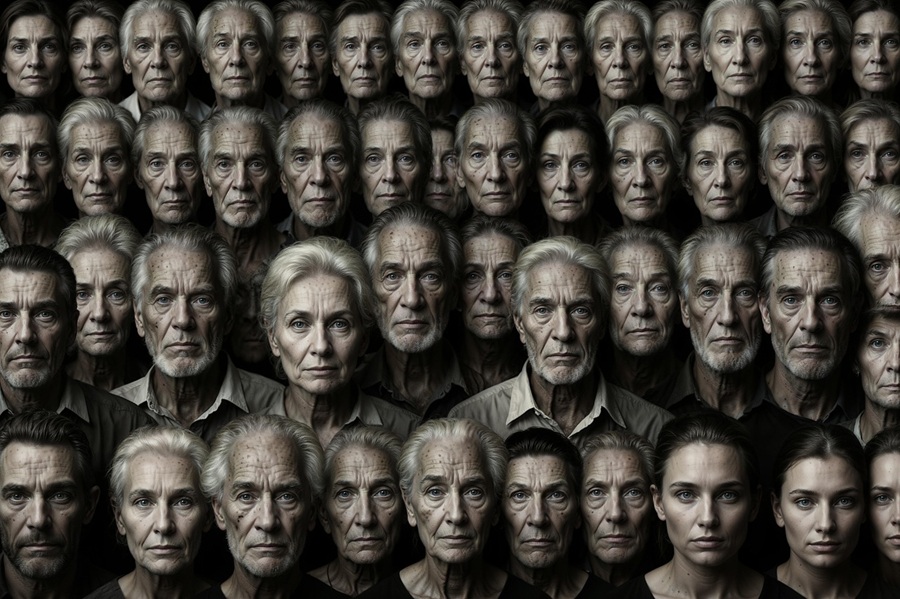

The great retirement

THE GREAT SCAM. Opinion section by David Cerdá

A quiet earthquake is gathering at the heart of education: the mass departure of veteran teachers who have sustained our classrooms for decades. Political indifference, waning vocational security and demographic ageing are opening a void that threatens not only the system’s continuity but the very transmission of the craft of teaching. And although the warning bells have been ringing for years, we behave as if the next generation will replace the last automatically.

The baby-boom cohort is retiring en masse. It is estimated that in the next ten years more than five million workers aged over fifty-five will leave the workforce — with education among the sectors most affected. A report by the Fundación Conocimiento y Desarrollo predicts that one in three university academics will retire; the SEPE (Spain’s Public Employment Service) notes that only around 8% of primary teachers are under thirty, while nearly 40% of secondary teachers are over fifty. And the reader can be confident that the sheer difficulty of teaching today, the profession’s loss of social standing and the broader decline of education will do little to entice people into filling those posts, demographic trends notwithstanding.

Put aside for a moment the obvious: a teacher with thirty years’ service has delivered thousands of lessons, taught hundreds of cohorts and weathered multiple curriculum reforms. That accumulated methodological and human capital is not replaced overnight. The generational turnover coincides with far more diverse classrooms — migrant pupils, pupils with special educational needs and social divides driven by rising inequality. New entrants will need far more robust preparation than was required decades ago, and that preparation has not materialised. It goes without saying that in a country whose short-termism has been fuelled by political polarisation and inept government, the necessary handover has simply not been planned.

Speaking of retirement is therefore not a matter of statistics alone but of the erosion of a professional culture. Those retiring learned how to survive cuts, pedagogical fads and repeated reform; they have seen both the best and worst of state schooling and have kept institutions afloat with a mixture of patience, authority and common sense. They were not saints, and their faults will be inherited by their successors. Yet we expect new generations to remedy the problems left behind. This mismatch exposes a system that has long relied on the inertia of individual dedication rather than on collective, forward planning.

In the 2025 competitive examinations for Secondary and Vocational Education, roughly 24 % of the posts advertised were unfilled. We remain absorbed by superficial debates while the system buckles and its fissures multiply. Society expects schools to redress inequalities, heal social wounds and produce critical citizens and capable professionals, yet it does not accept that doing so requires trained, recognised and supported teachers — an adequate number of them. This great wave of retirements is no mere demographic footnote; it marks the end of an era for a country that has lived on the labour of others’ vocation without asking whether future generations will wish — or be able — to shoulder the same burden. Succession cannot be improvised: it demands a long view, genuine political commitment and an educational community that understands quality is not decreed but cultivated.

UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring Report 2023 puts it plainly: “The future of education depends on systems’ capacity to attract, train and retain the best teachers, not simply more teachers”. This is not a slogan to pin to the wall but an urgent diagnosis: without a solid professional base, every educational project becomes empty rhetoric. Every generation of teachers we fail to recruit today is another generation of citizens who will tomorrow pay the cost of our neglect. Improving pay — especially in rural areas — will be critical to drawing more young people into the profession. There is, undeniably, something powerful in the act of teaching; we must create the conditions for that spark to rekindle a sense of vocation and to foster professionalism. In universities, a sensible mix of hiring early-career researchers and encouraging key professors to delay retirement voluntarily could preserve research lines while opening opportunities for newcomers. That will require sustained effort in the years ahead: rolling up our sleeves and acting with non-partisan loyalty and a genuine sense of public purpose.

We should not expect conventional politics to deliver all the answers. Civil society must find its channels; salvation will come from a fervent, tangible and substantial love for the polis — a love in which families, through the way they relate to teachers and schools, will play a decisive role. Far from being only a problem, this “great retirement” is a historic opportunity to restore public esteem to the teaching profession. As Condorcet observed, education is the means by which society can be continually improved; if the generational transition of teachers fails, what will be interrupted is not a career path but the very possibility of social progress and prosperity.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons