- TEACHER TALES

- 8 de September de 2025

- No Comment

- 12 minutes read

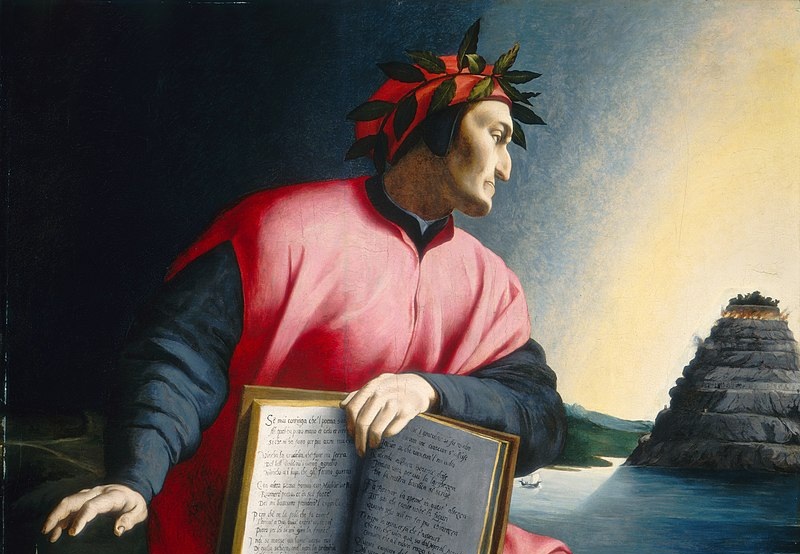

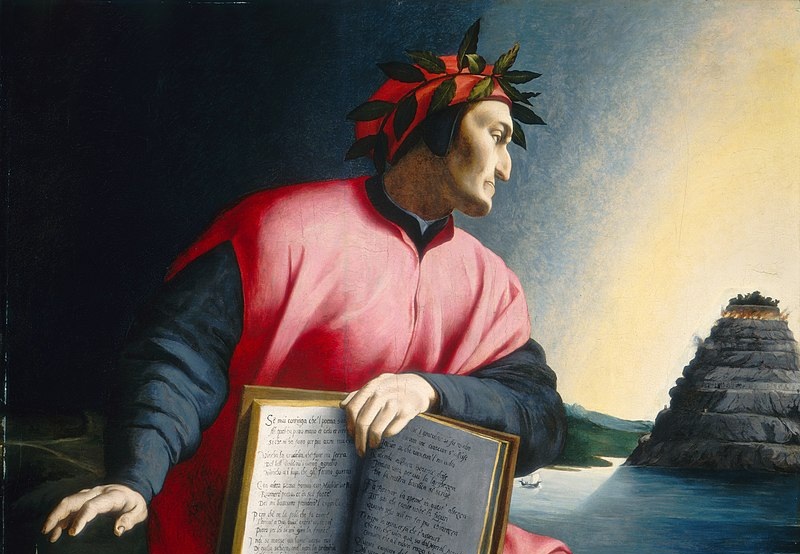

The Dantesque baccalaureate

The Dantesque baccalaureate

Or the havoc wreaked by the scarcity of university places in certain degrees and the inflated grades handed out in private schools – with a few closing remarks

There is no such thing as the baccalaureate. There are many. Many versions of that liminal passage, that halfway point in academic life — to borrow from Dante — and they differ widely depending on latitude, specialism, and, above all, what pupils hope to do once it’s over.

I won’t go into the tragedy of those left behind. The sharp edges of school dropout, academic failure or that old chestnut — meritocracy — are many and keen. What follows concerns mainly those who, having made it as far as the baccalaureate, want to go on to Spanish state universities — because they can’t afford private ones — and find themselves faced with entrance grades that are sky-high. Their original sin is wanting to be doctors, dentists, aerospace engineers, mathematicians or physicists — to name just a few of the degree courses with the highest entry thresholds in Spain, without even touching on joint honours degrees: programmes designed from the start to admit only the rare few who can cope with two demanding courses at once.

The university system ought, at the very least, to expand the number of places on those degrees where the current supply fails to meet social needs. The case of medicine is a well-worn one. We need to import doctors, because we don’t train enough of them — especially in certain specialities. In the face of this situation, private universities — both Spanish and international — have a field day. For those who can afford them, of course. A greater offering, in medicine and other essential and oversubscribed degrees, would make a real difference to those students who, by just a few decimal points, remain locked in their own private Dantesque circle.

Would such a measure make no statistical difference? Perhaps not. But it would mean everything for the lives of those individuals who, thanks to that marginal increase, could have a go at realising themselves — and in doing so, help resolve a national problem. Even so, a boost in available places would merely shift cut-off marks by a fraction — perhaps a whole point at most — but it would do little to soothe the anxiety, the nerves or the pressure bearing down on today’s baccalaureate students. The unlucky ones caught in the brutal competitiveness that scarcity breeds. They can’t afford to slip up. Some cry when they get a mere B. They suffer, and break down — because they know that meagre triumph simply won’t cut it.

Families with the means have already paid for private schooling, where a generalised grade inflation at baccalaureate level (which accounts for 60% of the final university entrance grade in Spain, with the remaining 40% coming from the Selectividad exam) is the norm compared with state schools — and topped this up with private tuition as needed. Not to pass but to raise their grades. There is meritocratic doping1. The poor, when left to their own devices, have taken lately to consulting some generative AI, if they’re lucky enough to have internet access.

Inequality has reached such proportions that perhaps it’s time to reconsider the weighting of the university entrance exam — the Selectividad — and have it count for at least 50% of the total score. Or 60%. Or 70%, just to be safe. Yes, your whole future hangs on a few days. But looking back, I think I’d rather have taken my chances there, even knowing I was already at a disadvantage compared with the doped — those who got their grades up over several attempts, with support in all its forms — as varied as the devil’s tricks, simply because their parents could afford to pay.

By the way, we teachers are now receiving emails not only from parents but also from tuition centres and from the many university students making a bit of extra money running tutoring sessions. Pressure, following Pascal’s principle, is transmitted in all directions. And it reaches us too.

Now, not all baccalaureate teachers are the same. Some go out of their way for their students — they teach, support and comfort when needed. Professionals who do their best to be the system’s own bálsamo de Fierabrás2. But others, self-styled gatekeepers of the purity of their discipline, lose all sense of perspective. Why not bump that C up to a B, if the student worked solidly all year? That’s not grade inflation — it’s justice. Especially if you’re in a state school, and you’re aware of what goes on in the private sector. And why not bump that B down to a C, if the student barely handed in any work all year, even though they passed the exams? That’s fair and just — this time for the pupils who did put the work in. Often, teachers are morally compelled (or instructed by the board, or subject to other pressures) to pass a student — and yet, the student who gets a D is not allowed to pass with a C, the C doesn’t move up to a B, and so on. Make a note of it: I am generalising. These are complex realities, and best understood by those who live them every day on the educational front line.

But let’s turn to a couple of classroom-level suggestions. Personally, I always included in my syllabus the possibility of “rounding” the mark at baccalaureate level — and used it at the end of the year to take account of a student’s overall effort. And in this age of potential parental complaints, it’s best to have such rounding mechanisms written down — and explained to students on day one. They serve both to reward those who have put in the work, and to penalise those who’ve been dossing about. Continuous formative assessment implies that teachers ought to assess effort, perseverance and progress. With clear evidence gathered throughout the year, I’d argue that rounding up the mark is entirely appropriate. It’s a way of documenting and justifying, for example, how a borderline fail might easily be bumped up to a pass — an extreme case, but illustrative.

Another issue is end-of-year exams to raise marks. These are standard practice in private schools — in state schools, they’re used far less, depending on the teacher. Most subjects are cumulative, so a weighted term-based evaluation system (e.g. weighting terms 1, 2 and 3 as 1, 2 and 3 respectively) makes sense, with a final exam at the end of the year offering the chance to raise marks — and retake the subject if needed. This option should, once again, be stated clearly in the course plan, and explained in good time. These final exams also help familiarise students with the format of the university entrance tests. That said, the rules surrounding these exams — both for grade improvement and recovery — need to be crystal clear.

In the case of improvement exams, participation should be voluntary. It is absurd — unless one is being lazy or unethical — to threaten students with lowering their mark if they perform worse on the exam than throughout the year. One may advise them not to hand in the paper if things aren’t going well, of course. But given the current climate, my recommendation is that the exam for improving one’s mark and the recovery exam should be the same — pitched at the course level. And who sets that level? Thankfully, the university entrance exams do. Teachers have plenty of past papers. In short, one sets a final exam that matches Selectividad conditions. If the course has been taught properly, this shouldn’t be a problem.

And what should the maximum achievable grade be? If the exam is only for passing, there should be a cap. But if it’s for raising one’s mark — why impose a limit? I assure you: with a well-designed exam, student performance regulates itself. I never once saw, in science or technology subjects, a student score more than a B on a retake, or increase their mark by more than two grades in a final exam.

But, just like in the Divine Comedy, beyond the many Dantesque circles of primary, secondary and baccalaureate education, there are more to come. The spheres of paradise — where the fruits of all this effort might finally be reaped — still lie far ahead:

| E sappi che dal grado in giù che fiede a mezzo il tratto le due discrezioni, per nullo proprio merito si siede,ma per l’altrui, con certe condizioni: ché tutti questi son spiriti asciolti prima ch’avesser vere elezïoni.Ben te ne puoi accorger per li volti e anche per le voci püerili, se tu li guardi bene e se li ascolti.Or dubbi tu e dubitando sili; ma io discioglierò ’l forte legame in che ti stringon li pensier sottili. | And know that there, below the transverse row that cuts across the two divisions, sit souls who are there for merits not their own,but—with certain conditions—others’ merits; for all of these are souls who left their bodies before they had the power of true choice.Indeed, you may perceive this by yourself— their faces, childlike voices, are enough, if you look well at them and hear them sing.But now you doubt and, doubting, do not speak; yet I shall loose that knot; I can release you from the bonds of subtle reasoning. |

Students: when someone tries to downplay the merit of all those years of investment, to belittle or scorn your achievements, your sweat and your struggles — do not hesitate to send them off to a suitable circle of torment. You’ll always find one that fits.

___

1 artificial boosting of grades through tutoring, repeated attempts and financial privilege.

2 According to Cervantes’ Don Quixote, a mythical panacea that promises much and cures little.

References:

Dante Alighieri, Divine Comedy, Paradise, Chant XXXII, verses 37–51. This translation, from Digital Dante, is a collaboration among the Department of Italian, Columbia University Libraries, and Columbia University Libraries’ Humanities and History Division.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons