- Humanities

- 25 de September de 2025

- No Comment

- 8 minutes read

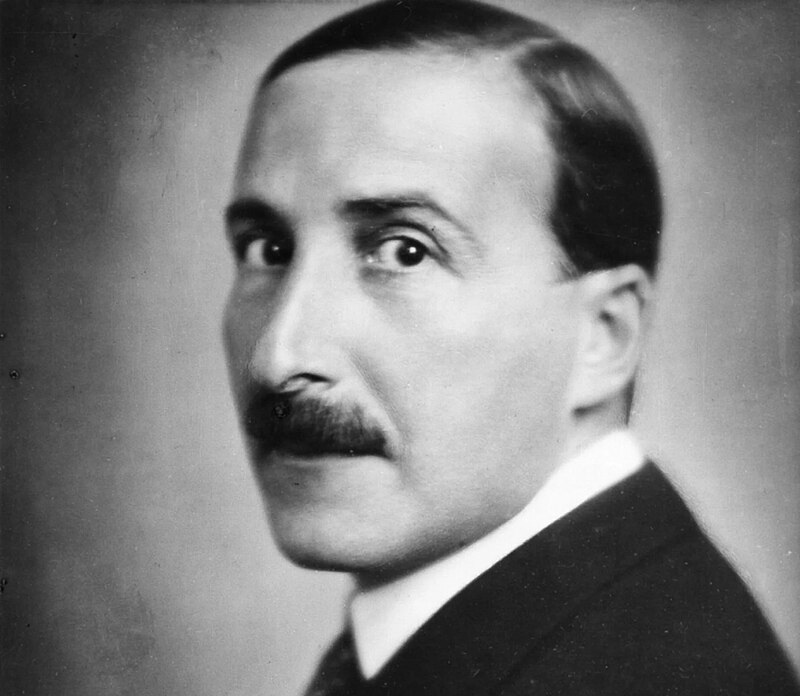

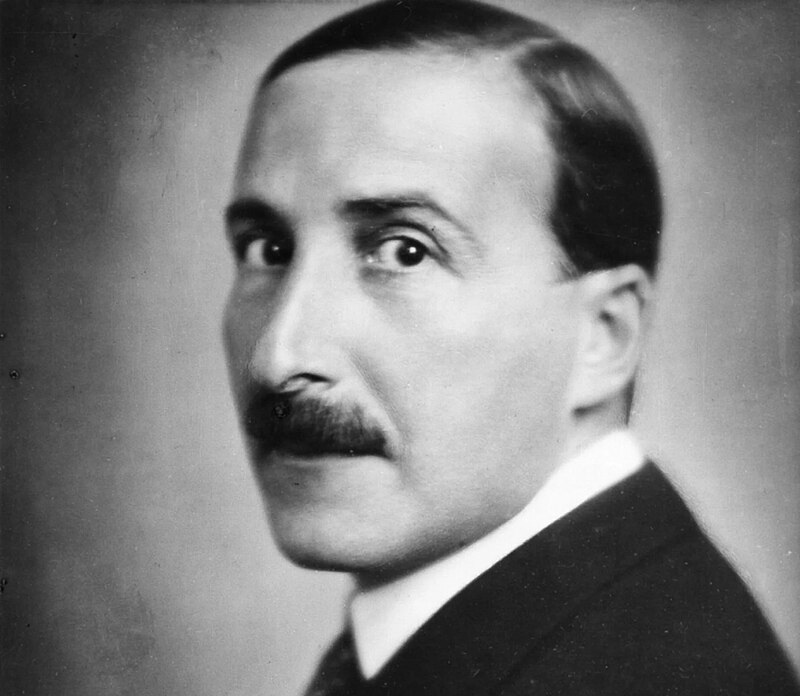

Stefan Zweig in Moscow

Stefan Zweig in Moscow

Stefan Zweig was invited to the Soviet Union in September 1928 to take part in the centenary celebrations of Lev Tolstoy’s birth. He spent two weeks there and wrote a highly admiring account of his experience. What impressed him most was the cultural atmosphere he perceived in every corner of the country. In a hastily penned prelude to his travel notes, Zweig wrote:

“A few lines in haste. Today I visited the Dostoyevsky Museum, the splendid historical museum, took part in the opening of the Tolstoy House (my book on Tolstoy is on sale at every street corner for 25 kopecks and hawked like La Hora by street vendors). In the afternoon I visited Boris Pilniak’s house, where many Russians had gathered; afterwards I stopped by the antique shops and took a drive through the streets. Late in the evening I attended a performance of Eugene Onegin at the opera, and now, at midnight, I am off to Tula, where I shall arrive tomorrow, Wednesday, at six. Then on to Yasnaya Polyana, and at night once again the sleeper train for the return journey”.

Zweig barely stood still: for his first Thursday on Russian soil, no fewer than ten visits and four museums were scheduled. Among the formal receptions was one with Maxim Gorky, who until the 1930s acted as a kind of ambassador for renowned foreign writers invited by the regime. On Sunday, he travelled to Leningrad, at the invitation of his publisher. What writer would not fall in love with a city where your books are shouted from the street corners and where you are treated with the utmost consideration?

Yet the secret of this success may well lie in the precise timing of Zweig’s arrival. In 1928, the benefits of Lenin’s New Economic Policy were still visible; Anatoly Lunacharsky still had a year left as head of the People’s Commissariat for Education and Culture; and 1928 was also the year Trotsky was finally defeated through Stalin’s political machinations. In 1928, few could yet imagine what was to come, particularly from 1934 onwards, when Kirov was assassinated. Boris Pilniak, for instance—translated into Spanish by Andreu Nin in 1931—would be executed in 1938, at the height of Stalin’s purges.

Lunacharsky’s liberal and reformist policies—responsible for the flourishing of the Russian avant-garde and its striking poster art—would be forgotten in the following decade, despite the fact that the same minister had also purged thousands of teachers. The 1930s would be marked by the suicides of poets, and by writers pleading for bread and mercy from the supreme leader. Everything Zweig saw, in one way or another, was on the brink of vanishing. He was aware that visiting Russia was something of a romantic act of exoticism for those disillusioned with old Europe:

“What other journey today could be more interesting and fascinating, more enriching and stirring, than a visit to Russia? While Europe, and especially its great capitals, undergo an egalitarian transformation that renders them increasingly similar to one another, Russia lives a separate, incomparable life. Here, it is not only the material world that captivates our gaze and aesthetic sense—perpetually surprised by architectural depth and a renewed popular energy—but also the spiritual sphere, which takes on unique forms as it sheds its past and projects itself into an equally singular future”.

What Zweig most admired was the opening of all the country’s art galleries and the ease with which the working population could access the great museums. Among them, he particularly highlighted the Tretyakov Gallery, where one could admire as many works by Van Gogh, Manet, Courbet and Gauguin as in Paris itself:

“To gain even a fleeting impression of the forty or fifty museums in Moscow would require weeks, if not months; one simply cannot imagine the priceless and fabulous treasures they contain. The Marxist idea that everything belongs to everyone finds in the sphere of art its most eloquent expression”.

Peasants, soldiers, and countless groups of children filled these spaces, thanks to a visionary and democratic concept of cultural management.

The tone in Leningrad was the same:

“And here, in this chamber of the Hermitage, in this space that is princely rather than imperial, in this palace of the tsars, in this city built upon inexpressible wealth and senseless extravagance, one senses that inconceivable tension—unimaginable to the European spirit—that must have existed between those two utterly separate worlds: the world above and the world below, of sacrilegious excess and of unfathomable poverty and the hellish hunger endured by the peasantry”.

A social divide so absolute that only violent rupture could redress it. Towards the end of the book, Zweig returns to social reflection in relation to Tolstoy, wondering how a champion of Christian libertarianism, a principled pacifist, could come to be seen as a forerunner of a clearly statist and hierarchical revolution, built upon the drive for industrial progress. Here Zweig was remarkably prescient when he suggested that Tolstoy’s ideas might have served far better to inspire a figure like Gandhi than either Stalin or Lenin. For Tolstoy, the State was Satan, and his concept of revolution was far more spiritual than the Bolshevik thrust.

Nonetheless, Zweig allowed himself to be imbued with official optimism, and he expressed a certain understanding of the revolution’s achievements—albeit without the dogmatism that would dominate the 1930s, when intellectuals became deeply polarised between fascism and communism. Zweig attempted to challenge the image of a militarised and ruthless Soviet Union. At the border post of Negoreloye—now in Belarus—he noted:

“Nor can I see any of those red guards, described by many of my predecessors on this journey as picturesque, diabolical figures, implacable and bristling with weapons. I see only a couple of officers, calm in demeanour and unarmed”.

Something must have changed in the following two years, however, for by 1930 Andreu Nin, deposited by the GPU on the Estonian border, was warned that he could be shot by snipers if he attempted to cross no man’s land on foot and unescorted. Or perhaps Zweig failed to notice certain details, or perhaps surveillance was simply very discreet… Or perhaps the memory of wartime Europe between 1914 and 1920 still lingered in his mind, rendering the Russian frontier comparatively amiable and liberal:

“Two or three railway lines link Russia to our European world, and each of them possesses a subdued, hesitant rhythm. One recalls border crossings during the war, when only a select few, carefully vetted individuals were allowed to cross those invisible lines separating the states”.

He found the streets of Moscow teeming with people. Yet even in this vibrancy, memories of the grim post-war years resurfaced:

“Despite this vitality, there is something in the street that seems muted. It is the buildings, the houses—they have something gloomy and dark about them. The buildings lining this feverish activity are all old and crumbling, like elderly faces, wrinkled, their eyes blind and encrusted. One is reminded of Vienna in 1919”.

“The doorways are dark and hesitant”, the traveller concludes.

Zweig’s articles on his Russian journey were published in Vienna’s Neue Freie Presse between 21 October and 6 November 1928—precisely one year after Walter Benjamin completed his Moscow Diary.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons