- Opinion

- 21 de November de 2025

- No Comment

- 11 minutes read

Rummaging through the attic of memory… John Dewey and progressive education

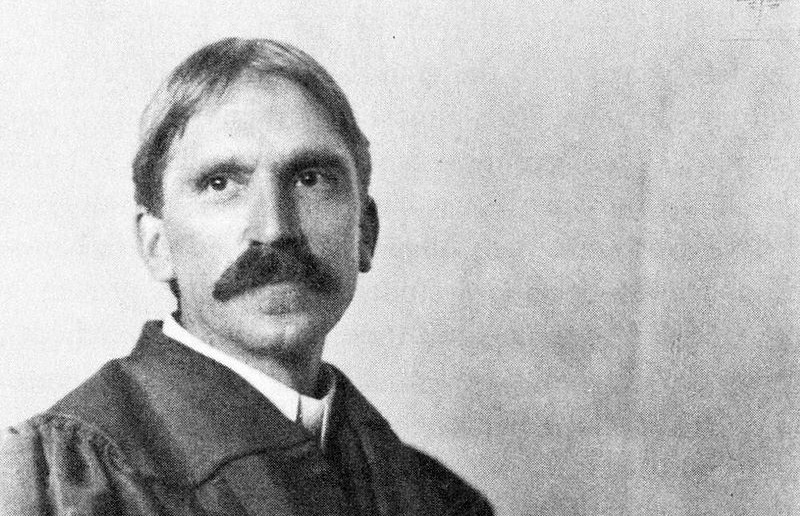

John Dewey at the University of Chicago in 1902. / Wikimedia

Felipe J. de Vicente Algueró

It is hardly an exaggeration to say that most people —teachers above all— agree that education is in a parlous state. Even those who insist it is perfectly healthy cannot be entirely convinced, given how loudly they call for ever more teacher training, as though the alleged lack of such training explained every malaise in the system and not, heaven forbid, the ideas that have inspired educational reforms over the past few decades.

“At what precise moment had Peru fucked itself up?” Zabalita’s overquoted question in La Catedral can easily be recast: At what precise moment had Spanish education fucked itself up? (A note for the post-LOGSE generation (those educated under Spain’s 1990 LOGSE reform): the line comes from Mario Vargas Llosa’s Conversation in the Cathedral— Isabel Preysler’s fleeting husband, who was an outstanding novelist). Things began to unravel with the arrival of constructivist ideas. Clumsily absorbed by pedagogues of a ’68 vintage, they eventually crystallised into what came to be known as “the educational reform”, the cornerstone of the 1990 Ley Orgánica de Ordenación General del Sistema Educativo (LOGSE).

The first patriarch of all this was Jean Piaget (1896–1980). In Spain —and particularly in Catalonia— he was revered. The University of Barcelona awarded him an honorary doctorate when he was already a venerable old man. Piaget was a first-class scientist, a first-class psychologist. I very much doubt he would have welcomed being called a pedagogue, let alone a psycho-pedagogue. His work on the developmental stages of intelligence remains solid. He was not especially interested in education as such; he was a professor of psychology. Moreover, his theory of “assimilation” as the initial phase of mental information-processing does not dismiss memory; on the contrary, it values it — nor does it disparage theoretical knowledge, conceptual understanding or factual information as part of intellectual development.

The trouble began when others tried to apply his ideas to education. Here pedagogy —and psycho-pedagogy— took over. Take Lev Vygotsky (1896–1933), trained first as a doctor and later a Soviet pedagogue. He taught in a Pedagogical Institute and in 1926 published his best-known work, Educational Psychology, marking the birth of psycho-pedagogy. Vygotsky is often credited as the true father of constructivism, leaving Piaget as the elderly patriarch (despite their being contemporaries). Yet the most influential constructivist was David Ausubel (1918–2008), who diverged somewhat from Piaget and popularised the core ideas of constructivism in an accessible style. Though trained as a psychologist, he devoted his career to Educational Psychology —or, in effect, Psycho-pedagogy.

Ausubel inhabited the North American world of Pedagogy and Educational Psychology. And in that world the most influential figure —the true precursor of constructivism— was John Dewey (1859–1952), the great populariser whose pedagogical ideas eventually reached even the most remote Spanish classroom. Dewey was a pedagogue through and through: professor of Pedagogy in Chicago and elsewhere. In 1896 he founded an Experimental School in Chicago to put his theories into practice. He was also a philosopher (though one with a highly debatable notion of philosophy), closely aligned with American pragmatism, and a staunch defender of democracy —for which education should serve as both instrument and safeguard. He was widely read and swiftly translated into Spanish (first in 1926). His works appeared in Spanish throughout the 1940s and ’50s, leaving ample time for his ideas to take root in Spain.

Dewey is, in short, the perfect pedagogue —the patron saint of the profession. Philosophy, in his eyes, must serve Pedagogy. Hence his uncompromising rejection of speculative thought. Aristotle, Aquinas, Kant —even Marx— were of no use to him. Dewey was an out-and-out empiricist, a naturalist and a convinced pragmatist. All philosophy, including the philosophy of education, had to submit to empirical investigation.

From this starting-point, every teaching method and every pedagogical tool had to be grounded in empirical results. Hence his enthusiasm for experimental schools and experimental teaching, in which the mere transmission of knowledge counted for little. Dewey equated education with life itself: an unending reconstruction of experience, through which knowledge deepens, thickens and acquires meaning. Education, he wrote, grows “through experience, by virtue of experience, and for the perfecting of experience”.

Education therefore means cultivating a pupil’s capacity for inquiry —developing what we now call “competences” and “attitudes”. As Dewey put it: “It is no longer a question of the pupil’s mind merely studying or learning, but of doing things required by the situation [prepared for that purpose] which result in learning. The teacher’s method consists in determining the conditions that stimulate self-educative activity and in cooperating with pupils’ activities so that they end up learning” (Francisco Ornar, John Dewey: Filosofía y Exigencias de la Educación, Revista Educación y Pedagogía 12 and 13). Note the two key terms: situation and learning. Does it sound familiar?

Concepts matter less than skills. Hence Dewey’s interest in introducing into education learning grounded in inquiry itself, or in the resolution of problems. The teacher becomes a guide, fostering each pupil’s abilities. Teaching must never rely on the traditional lecture; it must be collaborative. Nor should the teacher prevent a pupil from doing what he or she believes to be right, even when the teacher knows it is wrong: for Dewey, pupils possess the right to err —and to err on their own terms.

Dewey’s pedagogical method can be summed up in a single passage:

“Let the pupil be genuinely situated within his experience, drawn into a continuous activity that attracts him for its own sake; let that situation give rise to a genuine problem capable of stimulating thought; let the pupil acquire the data and make the observations required to tackle it; let possible solutions be suggested, which he must then develop and organise; and finally, let him be given opportunities to test his ideas by applying them, clarifying their content and discovering their validity for himself”. (Francisco Ornar, ibid.)

A structured, prescriptive curriculum therefore has no place. Dewey writes: “Between the child and the curriculum, which should be subordinated to which? The curriculum must be subordinated to the child: It is their aptitudes that must be strengthened, their abilities that must be exercised, and their present attitudes that must find expression” (The Child and the Curriculum, 1902).

Alongside skills and abilities come attitudes —a crucial part of Dewey’s pedagogical vision. He was probably the first to place attitudes at the centre of teaching and learning. No curriculum worth its name lacks a catalogue of attitudes to be cultivated —and, even harder, assessed. Schools must produce good citizens for democracy —the still imperfect American democracy of his time— and thereby improve it.

Moral education, anchored in practical values, is essential. Dewey’s praise of success is striking: “We may safely conclude that things would be much better if more people took a conscientious interest in succeeding in outward things” (Theory of the Moral Life, New York, 1960). The attitudes he championed —uprightness, respect for the law, tolerance, solidarity, benevolence— were those he considered vital for a participatory democracy (Democracy and Educacion, 1916). Dewey was an American liberal —for his time, a “progressive”, and now considered the father of “progressive education”. For him, the school was an engine of social transformation. In his Experimental School, pupils debated, participated and helped choose their projects.

When one examines the pedagogical premises underlying Spain’s so-called educational reform, the Deweyan imprint is unmistakable. Some of the very concepts seem lifted verbatim from Dewey’s books, long treated as canonical in Faculties of Arts (where Pedagogy was a specialisation). One might say, in a certain sense, that with Dewey Pedagogy attains a higher academic standing, breaking away from Psychology in order to assert itself as an independent “science” in its own right.

A final note. Dewey spent his life teaching in universities, but he certainly knew children: he had six with his first wife and, decades later, at eighty-four, remarried and adopted two more —eight in total. He also directed the Laboratory School he had founded in Chicago. Its foundation was what we now call “project-based learning”. Its method deserves quoting: “The pupils, divided into eleven age groups, carried out a range of projects centred on different historical or contemporary occupations. The youngest children (aged four and five) engaged in activities familiar from their homes and surroundings: cooking, sewing and carpentry. Six-year-olds built a wooden farm, planted wheat and cotton, processed them, and sold their produce at market. Seven-year-olds studied prehistoric life in caves they had constructed themselves, while eight-year-olds focused on the work of Phoenician navigators and later adventurers such as Marco Polo, Columbus, Magellan and Robinson Crusoe. Local history and geography occupied the nine-year-olds, and ten-year-olds studied colonial history by building a replica of a pioneer-era room. The work undertaken by the older groups was less strictly tied to particular historical periods (although history remained an important part of their studies) and more to scientific experiments in anatomy, electromagnetism, political economy and photography”.

(Robert B. Westbrook, “John Dewey (1859–1952)”, Perspectives: Quarterly Review of Comparative Education, Paris, UNESCO, vol. XXIII, 1993).

We may never know whether Dewey used the phrase “project-based learning”, but he would certainly have revelled in it. His Laboratory School ultimately failed and closed. Internal problems in 1904 prompted his resignation; he moved to Columbia University and never again sought to found such a school. His ideas never really took root in American schools and were later blamed for the lamentable state of American education —particularly once the Soviets surged ahead in the space race. Soviet schools taught knowledge through more traditional means. And so pedagogical experiments were relegated to the attic of memory —until they resurfaced here. Never have such stale ideas been defended with such zeal as in Catalonia, marketed as “progressive” or “new pedagogy”. And some people even believe them. Just ask the Fondación Bofill1.

___

1 The Bofill Foundation is a Catalan think tank devoted to education and social policy, influential in shaping debates on schooling and inequality. Known for its strong advocacy of “progressive” pedagogical reforms, it plays a prominent role in the region’s educational discourse.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons