- Opinion

- 22 de January de 2026

- No Comment

- 6 minutes read

Pedagogism and anti-Enlightenment

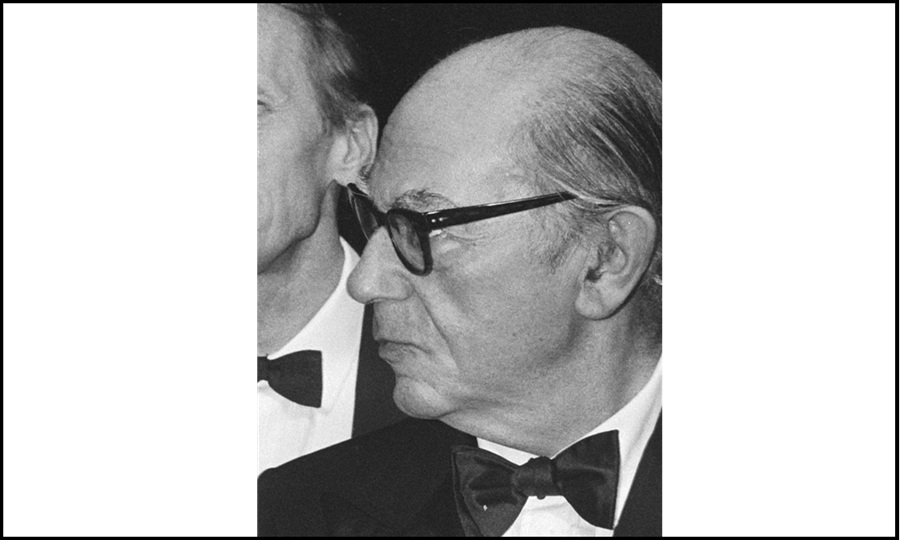

Isaiah Berlin during the reception of the Erasmus Prize, Oct. 1983 / Photo: Por Rob C. Croes (ANEFO) – GaHetNa (Nationaal Archief NL), CC0

Between 1770 and 1820 a cultural process unfolded that bears striking parallels with what has taken place in the West between 1970 and 2020. In order to diagnose the high-water mark of the anti-Enlightenment reaction associated with Sturm und Drang, Isaiah Berlin focused above all on three figures: Hamann, Vico and Schelling. Midway through The Counter-Enlightenment (1973), Berlin notes that “Vico’s works, unsystematic as they are, deal with many other matters, but their importance in the history of the Enlightenment lies in their insistence on the plurality of cultures, and on the consequent falsity of the idea that there exists a single structure of reality which the enlightened philosopher can see as it truly is and, at least in principle, describe in a logically perfect language—an idea that has obsessed thinkers from Plato to Leibniz, Condillac, Russell and their most faithful followers”. Put bluntly, Vico believed there could be a Swiss science and cosmos, a Chinese one, or Greek, Turkish, Basque or Welsh ones.

What particularly troubled Berlin was the realisation that mid-eighteenth-century Enlightenment rationalism had given birth to an anti-aristocratic meritocracy, whereas Democracy and Republicanism were, paradoxically, inventions of anti-Enlightenment Romanticism—driven by its fierce determination to show that there was no single, central way of reasoning about and organising culture and the universe. Diversity belonged to Rousseau and Novalis, not to Hume or Montesquieu.

Yet it was neither Vico nor even Rousseau whom Berlin accused of delivering the fatal blow to the optimistic progressivism of a certain Kant or Condorcet. That role fell to a theologian and philosopher from Königsberg, J. G. Hamann. “If Vico wished to shake the pillars on which the Enlightenment of his day rested”, Berlin writes, “Hamann wished to crush them”. Educated as a pietist—within the most introspective and inward-looking of Lutheran sects—Hamann was committed to direct communion between the individual soul and God, bitterly anti-rationalist, prone to emotional excess, and obsessed with intense experiences of moral obligation and severe self-discipline. My working hypothesis is simple: just as Hamann drew sustenance from the most traditionalist Protestant reaction, determined to resist the reforms of Frederick the Great—so eager to import French culture and its military and administrative practices into Prussia—so today’s anti-globalist reaction has taken the form of a civil religion strikingly similar to Hamann’s pietistic rigour.

Alarmed by the dissolution of earlier social orders, today’s middle class has generated pedagogism as a fetishisation of childhood and an almost millenarian exaltation of the New Man in a New Earthly Paradise. Above all, it seeks to escape the real state of educational affairs and to settle instead into a comfortable authoritarian utopianism. The difficulty with this outcome (Hamann fascinated Goethe much as Tonucci now hypnotises teachers) is that the result resembles not liberation but submission to the deregulatory demands of the economic order. A moral obligation bordering on self-abasement replaces the work ethic once sketched by Marx. In other words, neo-spiritual anti-progressivism does not deepen social egalitarianism; it consolidates socio-economic estates.

Pedagogism increasingly resembles a secularised Calvinism, or a millenarian pietism obsessed with the most militant utilitarianism. In little more than two decades, universalist ideology has been transformed into an ultra-particularist defence—if not outright sacred individualism. Proposals for immediate redemption without budgetary requirements (since each individual redeems themselves) owe more to nostalgic reveries of premodern worlds than to any materialist and responsible management of resources within a democracy, which is necessarily procedural. Translated plainly: instead of developing even a minimal common emancipatory culture, the new pedagogist pietism becomes entangled in a murky web of idealist voluntarism that, by omission, clears the way for every form of civic dispossession.

Since life itself will educate us; since the only authentic gesture is fusion with algorithmic nature; since love alone matters and only values generated by emotivist spectacle exist—there is no longer anyone left to emancipate, nor anyone to educate for meaningful, high-quality work. Labour and reading are deferred to another life, or reserved for an elite that quietly mocks us. Poverty is sanctified; those who submit to redemption and accept Revealed Truth are rewarded with incandescent words. And meanwhile, our pockets have already been picked while we drooled over universal love.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons