- Humanities

- 12 de September de 2025

- No Comment

- 22 minutes read

Oreste Camarca’s quartet and sextet (1895–1992) and the musical legacy of the Motu proprio

Oreste Camarca’s quartet and sextet (1895–1992) and the musical legacy of the Motu proprio

Oreste Camarca was an Italian-born musician, born in 1895 at Ascoli Satriano in the province of Foggia, who lived in Soria from 1925 until his death in 1992. Educated principally in Cádiz, he established himself in the modest Castilian city as a private tutor in piano and solfège. He also taught Italian, directed several choirs, and produced a relatively modest output as a composer. Admired by successive generations of Sorian residents for his pedagogical skill, his patience and kindness, he was known for his humble, reserved and prudent demeanour.

The Granadan composer and priest Juan Alfonso García used the term Motu proprio to denote a group of Spanish composers—all clerics—who throughout much of the twentieth century composed works with the aim of dignifying sacred music in their era (even though the majority also composed secular works), in adherence to the directives of the Motu Proprio [1] decrees promulgated by Pope Pius X in 1903 and 1904 under the influence of the Italian composer‑priest Lorenzo Perosi (1872–1956). Perosi’s pedagogical influence “was felt throughout the world” (Tomás Marco, 1983: 104), albeit “debatable” according to Marco; García (also cited by Marco) asserts: “His influence on Catholic sacred music was immense and Spain was no exception” (Marco, 1983: 104). William W. Austin, generally more favourable towards Perosi, emphasises that “His Masses and other liturgical compositions were performed extensively throughout the world within the Institution for which they were created” (Austin, 1984: 169).

The Works

On 14 June 1934, two works by Oreste Camarca received their premieres at the Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid: the Quartet for strings with choir in F‑minor, Op. 1, and the Sextet for strings with choir in B‑minor, Op. 2. The instrumental parts were performed by six soloists under the leadership of concertmaster Rafael Martínez of the Madrid Philharmonic Orchestra, while the vocal parts were sung by selected members of the Masa Coral directed by Rafael Benedito (García Redondo, 1986: 86; Delgado Encabo, 2006: 6). The Quartet follows the standard string grouping of two violins, viola and cello, while the Sextet is scored for two violins, two violas and two cellos. Both the instrumental ensemble and the dates of composition (the Sextet written between 1925 and 1927; the Quartet in 1927; Delgado Encabo, 2006: 6) suggest that Camarca may have composed them expressly for submission to the International Chamber Music Composition Competition organised by The Music Fund Society in Philadelphia, open from 1925 until the end of 1927. Camarca received no prize: in 1928 the first prize was shared between Bartók’s String Quartet No. 3 and Casella’s Serenata (Albrecht, 1980: 624). The second prize went jointly to H. Waldo Warner’s Quartet in E‑minor and Carlo Jachino’s Quintet. All the award-winning works were composed in 1927. No third prize or honourable mention was awarded (University of Pennsylvania, undated).

I have located four reviews of the premieres. Two were appreciative: by José Subirá in El Socialista (Subirá, 1934: 4) and an anonymous notice in ABC (1934: 47). The other two may be termed politely negative: by Joaquín Turina in El Debate (Turina, 1934: 6) and Julio Gómez in El Liberal (Gómez, 1934: 2). Three of the critics note that the audience at the premiere was not large; Turina does not comment on the size of the gathering.

The Sextet with Choir in B Minor, Op. 2., subtitled Nei dintorni di San Juan de Duero (“In the environs of San Juan de Duero”—referring to the remains of a medieval monastery near Soria), unfolds in four movements: Prelude: Assai lento; Andante; Allegro moderato; and Lento, as a tempo making. The movement count is typical of nineteenth‑century practice and of early twentieth‑century composers outside avant‑garde strands, although the predominance of slower tempi throughout is more marked than is customary.

The Quartet with Choir in F Minor, Op. 1, composed “In comemorazione del centenario della morte di Beethoven” likewise comprises four movements (numbered with Roman numerals, like in the Sextet), preceded by an unnumbered Introduzione: quasi adagio. The numbered movements are: I. Allegro molto moderato; II. Andante; III. Vivace; IV. Allegro con fuoco followed by Finale: quasi adagio. Though begun after the Sextet, the Quartet was completed first and adheres more to classical fast‑slow movement distribution.

In the Sextet, the first choral section (Ave Maria) appears twice in the first movement: initially a cappella, later joined by the six string players (Camarca, 1997: bar 107). A second vocal section, featuring the same Ave María text but set to different music, appears after the fourth movement has begun. In between, there is a brief quotation of the Ave María theme from the first movement, now presented with a homophonic rather than contrapuntal texture and using the words Sancta Maria instead of Ave María. The vocal section continues until the end of the movement. In this fourth movement, the choir never sings a cappella and is always accompanied by the strings.

In the Quartet, the inaugural choral entry— a concise Gloria in homophonic texture—a cappella, occurs after the midpoint of the first movement (around 10′01″ to 11′08″). In the closing movement the chorus assumes greater prominence in the Finale: quasi adagio. Vocal sections—sometimes a cappella, sometimes accompanied, sometimes repeating the earlier Gloria motif, sometimes presenting new thematic material—alternate with purely instrumental passages from ca. 15′32″ to the work’s conclusion.

Style

These works profess a highly conservative aesthetic. The incorporation of choir and the abundance of slow movements in the Sextet are almost the sole departures from convention. For instance, at 1′29″ of the Quartet’s final movement one hears the sole chromatic scale across both pieces, otherwise overwhelmingly diatonic in language.

The Sextet is, per se, a better and more cohesive work than the Quartet, regardless of the fact that the revision of the Sextet by Jesús Ángel León—which removes the repetitions [2]—makes the difference in quality appear even greater. The movements of both works are very long. The Sextet is a piece in which the string writing is rather unspecific and quite abstract; Camarca writes for the strings in a style not very different from that used for the voices. Despite this, it remains a better work than the Quartet, in which the composer does manage to write the instrumental parts in a more idiomatic, more quartet-like style.

Vocal writing fits more organically within the Sextet’s instrumental fabric than in the Quartet. The slow vocal sections in the Sextet—the Ave Maria, Sancta Maria—are inserted within equally slow movements; conversely, the Quartet’s Gloria—less effective in itself— is book‑ended by fast, ternary‑barred, major-mode passages evocative of a minuet, which bear little relation to the choral material. The fourth movement of the Quartet is better resolved structurally—the vocal passages are longer, conclude both the movement and the whole work, and blend more convincingly with the Allegro con fuoco opening than do the faster passages in the first movement.

As previously mentioned, Camarca would go on to direct several choirs; this may have something to do with the fact that I find the choral sections superior to the instrumental ones. The vocal parts are not only more effectively written for choir than the instrumental parts are for strings, but they are also more inspired. Although not always, Camarca tends to compose better when the tempo is slow and the mode is minor (with a more sombre sound) than when the rhythm is fast and the mode is major (with a brighter sound).

Jorge Jiménez Lafuente remarked of Camarca the composer of the Sextet that “his music seems to verge on the imminent musical Neoclassicism”. That characterisation errs by “imminent”: Neoclassicism, typically associated with the interwar years, had already been in full flower for several years—Stravinsky’s Pulcinella (1920) being the foundational work. Jiménez qualifies: “we do not dare to label him within that movement” (Jiménez Lafuente, 1997: 19).

Elsewhere Jiménez observes: “We might imagine ourselves holding a Renaissance manuscript, in which clarity of writing, homophony among voices and light contrapuntal treatment seem habitual (…) The choral text is liturgical, which may lead us to think of a certain stile antico inspiration in the score” (Jiménez Lafuente, 1997: 18-19). I concur: the Ave Maria in the Sextet is crafted in quasi‑Renaissance counterpoint. And recall that Palestrina and Lassus are among the influences Lorenzo Perosi absorbed in his liturgical works (Austin, 1984: 169). The Gloria of the quartet is somewhat reminiscent—due to its homophonic texture—of a chorale by Johann Sebastian Bach, although traces of nineteenth-century Italian operatic style also emerge.

The anonymous ABC critic spoke of the Quartet’s “purest classicism” and “a tendency towards romanticism, in certain passages of the most legitimate Mendelssohnian school” (ABC, 1934: 47). Jesús Ángel León described it with exemplary prose as an “admirable Quartet, full of Beethovenian resonance” (León, 2006: 12). I myself noted, in relation to the third movement of Sinfonia Spagna [3], that “its orchestration and harmony (…) are almost those of early Romanticism: in its scherzi, for instance, one hears echoes of Beethoven” (Rincón, 1995: 14).

Among the influences of such an eclectic composer as Lorenzo Perosi, William A. Austin highlights—not only those already mentioned, Palestrina and Lasso—but also Bach, Rossini, Weber, Schubert, and Liszt (Austin, 1984: 169). Two of the most important composers of the second half of the sixteenth century, arguably the greatest composer of the late Baroque, three early Romantics, and one from the high Romantic period. All of this aligns with what we have said about the two works under discussion.

When Jiménez Lafuente declines to label Camarca’s Sextet as Neoclassical, I would add that Camarca—a devout layman with close ties to members of the Daughters of Charity and successive generations of canons—seems more deeply influenced by Lorenzo Perosi or by a Spanish composer associated with the generation of the Motu proprio.

As Tomás Marco states of these composers:

“Throughout Spain, especially in the leading religious and devotional centres, a considerable effort to dignify sacred music developed, involving virtually all composers working in this genre. But it would be pointless here to list all the minor composers, whose works did not circulate widely at the time and remained confined to the locales in which they served” (Marco, 1983: 110).

The principal composer‑teacher in Cádiz of Oreste Camarca was José María Gálvez Ruiz (1874–1939), one such ‘minor’ Motu proprio composer in Marco’s reckoning. Although Juan José Espinosa Guerra’s biographical survey does not highlight Gálvez’s connection to the movement, it does catalogue his life and oeuvre: Gálvez was a priest, organist, and maître de chapelle of the Cádiz Cathedral, and director of the Royal Academy of Santa Cecilia in Cádiz (Espinosa Guerra, 1999: 360) teaching organ, harmony and composition, subjects in which Camarca excelled as his pupil, as in all the other subjects.

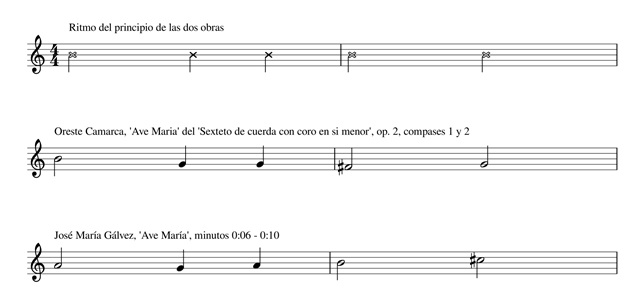

Notably, the rhythm of the first five notes of Gálvez’s Ave María for three treble voices is identical to that of the opening motif in Camarca’s Ave María from the Sextet, which gives rise to the most accomplished movement of the two works under study; just five rhythmic figures—if we consider rhythm alone—may suggest an influence or merely a coincidence (Camarca, 1997: bar 107; Gálvez, 2013, minute 00:06).

In both the Quartet and Sextet, the choral numbers evoke many of Perosi’s Mass movements performed ad infinitum in Italian and Spanish churches during Camarca’s lifetime. Camarca later directed a choir at the Colegio Sagrado Corazón in Soria, whose repertoire included at least one Perosi Mass. A manuscript of a Tantum Ergo for three voices and low organ (Fa bordon) by Perosi, expressly dedicated to the collegiate church of Soria (dated 5 April 1927) survives (Sánchez Siscart y Gonzalo López, 1992: 298); in the Musical Archives of Soria’s co‑cathedral of San Pedro there are six printed Perosi works, five of them Masses, alongside Camarca’s religious compositions (Sánchez Siscart y Gonzalo López, 1992: 347-348).

By contrast, it is unlikely that Camarca was familiar with Perosi’s string trios and quartets, which bear little resemblance to the instrumental sections of Camarca’s Quartet and Sextet, even though both sets of works remain within a similar tonal framework. Whether in his masses or his chamber music, the melodies of the composer from Tortona are more readily recognisable, and the structure of his movements more clearly defined, than in the two aforementioned works by the musician from Ascoli Satriano.

Camarca completed his composition studies with José María Gálvez in 1924; just a year later, in 1925, he began composing the Sextet, and in 1927, the Quartet. The Italo-Sorian composer developed his own style from the foundations provided by Gálvez, the music he had listened to, and the scores he may have studied up to that point.

Tomás Marco, who uses the term ‘generation’ to refer to the group of Spanish composers often brought together under the umbrella of the Motu proprio, states: “It will also have been noted that, by birth chronology, we have grouped together several generations” (Marco, 1983: 110). The first composer he mentions is Arturo Saco del Valle (1869–1932), who was older than José María Gálvez; the penultimate is Valentín Ruiz Aznar (1902–1972), who was younger than Camarca (Marco, 1983: 105–110).

In terms of age, Camarca could be considered part of this Motu proprio ‘generation’, but several factors prevent us from including him within it: firstly, however devout he may have been, he was a layman. Secondly, his religious works represent a minor part of his output.[4] Lastly, the Quartet and the Sextet are not sacred music, despite the sacred nature of their vocal texts. Nevertheless, the influence of the Spanish composers of the Motu proprio on the two works under discussion is undeniable — as is, more demonstrably, the influence of the masses composed by his mentor, Lorenzo Perosi.

___

[1] The words Motu proprio refer to a type of papal document distinct from encyclicals or apostolic exhortations. It is noteworthy that this generic designation has given its name, in music, to the specific motu proprio on sacred music.

[2] Jesús Ángel León’s revision of Camarca’s Sextet removes repetitions, corrects some errors, and transcribes the sextet parts for chamber orchestra. In the 2006 recording of the two works discussed here, conducted by David Guindano and Diego Gil Arbizu, León’s revision of the Sextet is used, but with the original instrumentation for six instruments.

[3] The third movement of Camarca’s Sinfonia Spagna is titled only with a tempo indication and is influenced both by Beethovenian scherzi and by flamenco zapateados. Camarca had a deep affection for Andalusia, especially Seville.

[4] Examples of these shorter works include the Himno a San Saturio, the two Gozos dedicated to San Saturio (Gloria a ti, Saturio penitente and Venturosos Numantinos), the motet Al gran numantino, two motets entitled Con himnos jubilantes, an Ave María for choir, organ, and string quartet, and the Himno del Colegio del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús (Sánchez Siscart and Gonzalo López, 1992, 133–135; Delgado Encabo, 2006: 6–7). It is unclear whether this Ave María is a separate work or an arrangement of the Ave María from the Sextet; what is known is that Camarca adapted the latter for white voices choir and that it was performed by the choir of the ‘Sagrado Corazón’ School in Soria.

Bibliography:

Printed sources

ALBRECHT, Otto E. (1980). “Philadelphia.” In SADIE, Stanley (ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, London, Macmillan, vol. 14, pp. 621–625.

AUSTIN, William W. (1984). La música en el siglo XX, vol. I, Madrid, Taurus, pp. 168–169.

DELGADO ENCABO, Javier (2006). “Oreste Camarca: resumen biográfico.” In the booklet accompanying the album Oreste Camarca: monográfico de la obra de Cámara por el Suggia Ensemble y la Coral de Cámara de Pamplona, Madrid, Banco de Sonido BS 061 CD, pp. 5–9.

ESPINOSA GUERRA, Juan José (1999). “Gálvez Ruiz, José María.” In CASARES RODICIO, Emilio (dir.), Diccionario de la Música Española e Hispanoamericana, vol. 5, Madrid, Sociedad General de Autores y Editores, p. 360.

GARCÍA REDONDO, Francisca (1983). La música en Soria, Soria, self-published, pp. 85–88.

JIMÉNEZ LAFUENTE, Jorge (1997). “O. Camarca: Sexteto con coro, op. 2 (1927).” Programme notes for the 5th edition of Otoño Musical Soriano, Soria, Ayuntamiento, pp. 18–19.

LEÓN, Jesús Ángel (2006). Untitled commentary in the booklet accompanying the album Oreste Camarca: monográfico de la obra de Cámara por el Suggia Ensemble y la Coral de Cámara de Pamplona, Madrid, Banco de Sonido BS 061 CD, pp. 11–12.

MARCO, Tomás (1983). Historia de la música española 6. Siglo XX, Madrid, Alianza Editorial, pp. 103–112.

RINCÓN, José del (1995). “Oreste Camarca (1895–1992), Scherzo de la Sinfonía en la menor.” Programme notes for the 3rd edition of Otoño Musical Soriano, Soria, Ayuntamiento, p. 14.

SÁNCHEZ SISCART, M.ª Montserrat & GONZALO LÓPEZ, Jesús (1992). Catálogo del Archivo Musical de la Concatedral de San Pedro Apóstol de Soria, Soria, Caja Salamanca y Soria, pp. 133–135.

Websites

University of Pennsylvania, sin fecha, Philadelphia Area Archives, Kislak Center for specials Collections and rare books anda manuscripts, Musical Fund Society of Philadelphia records, https://findingaids.library.upenn.edu/records/UPENN_RBML_PUSP.MS.COLL.90

Newspapers available in digital archives

Anonimous, 1934, «Informaciones musicales: Oreste Camarca, in the Círculo de Bellas Artes», ABC, 15 june, p. 47, available at:

Gómez, Julio, 1934, “De música: Oreste Camarca de Blasio”, El Liberal, nº 19838, 22 june, p. 2, available at:

https://hemerotecadigital.bne.es/hd/es/viewer?id=a5799900-58a0-461b-8e94-4fe625b9140a&page=2

SUBIRÁ, José, 1934, “Ecos filarmónicos: Evocación histórico-musical. Recitales y conciertos”, El Socialista n.º 7915, 17 june, p. 4, available at:

https://fpabloiglesias.es/wp-content/uploads/hemeroteca/ElSocialista/1934/6-1934/7915.pdf

TURINA, Joaquín, 1934, “Concierto de Camarca”, El Debate, 7658, 15 june, p. 6, available at:

https://prensahistorica.mcu.es/es/catalogo_imagenes/grupo.do?path=2001110781&interno=S

Scores, recordings and music distributed via online platforms

CAMARCA, Oreste (1997). Sexteto de cuerda con coro, op. 2 (1927), ed. Jesús Ángel León. [Unpublished score.]

CAMARCA, Oreste (2006). Oreste Camarca: monográfico de la obra de Cámara, Coral de Cámara de Pamplona and Suggia Ensemble, conducted by David Guindano, Madrid, Banco de Sonido BS 061 CD. [Compact disc.]

GÁLVEZ, José María (2013). Ave María (a tres voces blancas), Conjunto Vocal Virelay, conducted by Jorge E. García Ortega. Available at:

https://youtu.be/Im0yVgCWvEU?feature=shared

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons