- Technology

- 9 de December de 2025

- No Comment

- 5 minutes read

Linguistic technologies and the “bad speakers”

Foto: Gerd Altmann – Pixabay

Everyone is, at some point, a bad speaker. The term ‘bad speaker’ refers to anyone who, at a given moment, speaks “incorrectly” or makes linguistic errors—whether due to their dialectal variety, their pronunciation, interference from their first language, or even temporary conditions such as a cold or a hoarse voice (Hernández-Fernández, 2023). Historically, these bad speakers have been the ones shaping the languages of the world—and they will continue to do so.

The issue becomes particularly critical when language intersects with technology. Linguistic technology—defined as the technical means and systems that aid communication—is not ideologically neutral. Indeed, our perception of linguistic knowledge, whether our own or the machine’s, shapes our relationship with it. While a seasoned native speaker may bristle when an automatic spell-checker alters a perfectly correct word, a language learner often accepts the change without comment, trusting that the machine knows best. It is our awareness of linguistic knowledge that positions us either above or below technology.

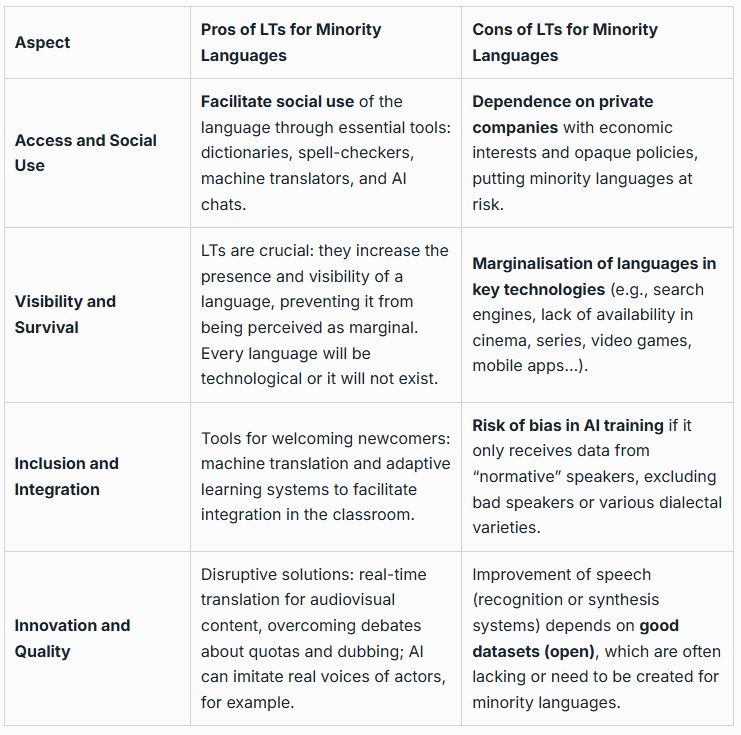

Linguistic technologies (LTs) can therefore be defined as all technical means, artefacts, and systems that enable or assist communication in one or more languages. Bad speakers are crucial to the development of these technologies, including machine translation and AI-based systems. There are, however, both advantages and drawbacks in the interaction between LTs and the world’s minority languages (Table 1).

For LTs to have a robust foundational dataset, participation from all speakers is essential—especially those who are considered ‘bad speakers’. Conversely, if machines are trained solely on data from “normative speakers” (and which variety, precisely?), the resulting bias can be deeply problematic. This is particularly acute in areas such as speech therapy, where speakers have linguistic difficulties and where data on language disorders is scarce. The technological challenge is to enable AI-based systems to detect, understand, and model the adaptive capacity of human speakers. This is a complex undertaking that requires a thorough understanding of the statistical properties of languages.

Then, for instance, will machine translation serve to support or suppress minority language usage? Risking the label of a “techno-solutionist”, one could argue that implementing high-quality automated voice and text translators might resolve longstanding issues in the audiovisual sector, as well as debates over language legislation and screen quotas. It is even conceivable that, in the near future, widespread use of individual devices could make real-time automatic translation available for any language, reproducing actors’ voices—a capability already emerging in some nascent local technologies.

In short, significant investment and technological effort are required to give visibility to minority languages. While it is crucial to depoliticise languages, there is also a need for deliberate linguistic policy within the technological domain. Education remains the cornerstone for combating prejudice and promoting linguistic use, embracing both ‘bad speakers’ and new technologies, within a delicate yet productive feedback loop.

Reference:

Hernández-Fernández, A. (2023). Tecnologia lingüística, ideologia i malparlants. En: IEC (2023). Usos socials del català. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans, 2023, p. 53-65. DOI: 10.2436/15.7100.01.6

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons