- HumanitiesLiterature

- 28 de January de 2025

- No Comment

- 5 minutes read

Joan Maragall: A Proponent of the LOMLOE Principles

Joan Maragall: A Proponent of the LOMLOE Principles

Did our educational system prioritise “automatic learning” before the passage of the LOMLOE in 2020?

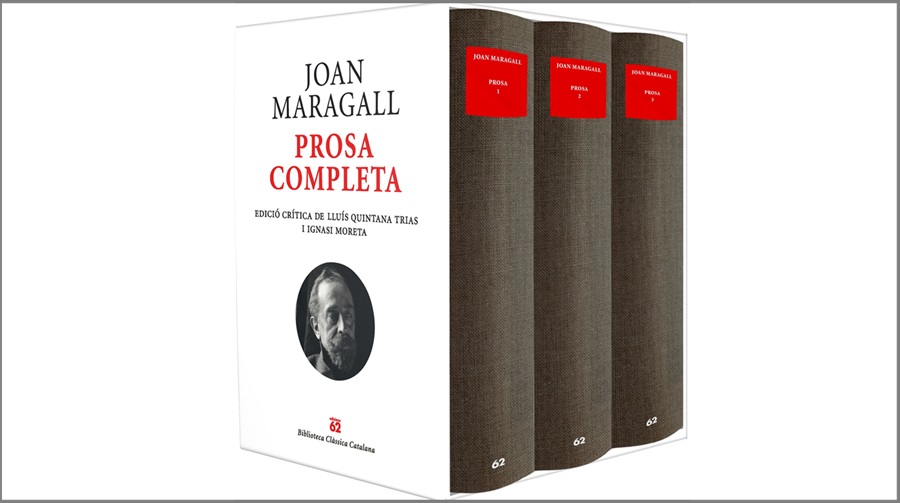

The recent critical edition of Joan Maragall’s prose, prepared by Lluís Quintana and Ignasi Moreta for the Biblioteca Clàssica Catalana series by Edicions 62, offers a unique window into the writer’s thoughts on a variety of subjects. Beyond organising his journalistic and theoretical materials in a coherent manner, this three-volume work also grants us, for the first time, a glimpse into Maragall’s role in the editorial offices of the Diario de Barcelona from 1892 to 1901. Here, we see not only the writer but also the journalist and even the news editor at work. Josep Pla long ago emphasised the significance of this formative period in Maragall’s career. As could not be otherwise, we find in the first volume of the work a thoroughly enriching and substantial article on education.

Published on 24 December 1896, Maragall’s article “Sobre educación” (“On Education”) was a review of Ricardo Monner Sans’s work Apuntes e ideas sobre educación a propósito de la enseñanza secundaria (Notes and Ideas on Education Regarding Secondary Teaching), published in Buenos Aires. As a close friend and correspondent of Francisco Giner de los Ríos, Maragall aligned himself with the most progressive pedagogical currents of the time. But let us allow Maragall to speak for himself:

“Mr. Monner Sans, in agreement with modern pedagogical authorities, believes that instruction is merely one aspect of education, and that teaching should not consist of rote memorisation but rather in engaging all faculties and senses. Teaching, especially at primary and secondary levels, should not aim to produce prodigies of memory or premature scholars but to shape individuals—balanced individuals”. (Volume I, p. 452)

The modernity and, indeed, the striking contemporary relevance of these ideas are undeniable.

Maragall takes constant shots at rote learning, but he does not stop there. He also targets the excessive rationalism of positivist approaches, which Unamuno also mocked:”It seems that in Argentina, as in other nations, these ideas, though favoured in academic circles and even in legislative preambles, have not matured enough to inform the substantive content of laws. These laws still incline towards an intellectualism that is detrimental to the generations shaped by it”. (Volume I, p. 453)

Quintana and Moreta’s edition reveals Maragall as a quintessential Romantic, whether in his religious, civic, or theoretical conceptions, or in his view of society and the world. This Romanticism was a legitimate reaction against the oppressive and stifling atmosphere of Spain’s Restoration era. The reforms inspired by Giner de los Ríos revitalised an otherwise rigid and fossilized context, one that was static and deeply dogmatic. He was not alone in his advocacy for life and vitality over academic rigidity; Montaigne, for instance, reacted against the artificial constructs of scholasticism by advocating for a minimally directive approach to education in 1588.

In 1895, educational responsibilities in Spain still fell under the Ministry of Development, led by Aureliano Linares Rivas, father of the renowned playwright and a staunch Cánovas supporter. It was not until April 1900 that Spain established a dedicated Ministry of Education. For Maragall, pedagogy was not a science; education was a matter best entrusted to well-educated mothers. He advocated for a seamless integration of family and academic environments, an idea echoed by contemporary reformists. While Maragall supported the education of women, he also confined them to the domestic sphere, viewing them as inextricably linked to reproduction and childcare. Catalan pioneers such as Dolors Monserdà and Carme Karr did not stray far from this liberal-bourgeois perspective.

The question we must ask ourselves today is this: Are Maragall’s ultra-Romantic ideas still innovative 130 years later? Was Spanish education, just 20 years ago, as dominated by rote learning, dehumanised, bureaucratic, exclusionary, excessively intellectual, and barren as it was at the end of the 19th century? Did our educational system prioritise “automatic learning” before the passage of the LOMLOE in 2020?

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons