- Science

- 15 de January de 2026

- No Comment

- 7 minutes read

Jerónimo de Ayanz: scientist, engineer, soldier, spy, adventurer and inventor

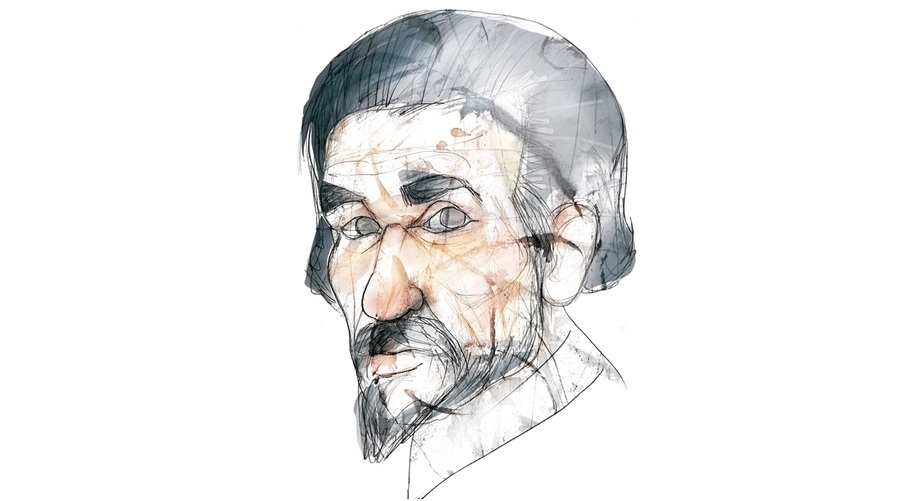

Portrait of Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont. Fundación Española para la Ciencia y la Tecnología, Eulogia Merle. / Wikipedia

Had he been born elsewhere, he would, without question, be a figure of global renown—celebrated in literary studies on his life and in scientific treatises for the brilliance of his work. He registered and applied the first steam engine a century before Savery in England and two centuries before Watt would turn it into the talisman of the Industrial Revolution. History offers many instances in which some have taken the credit owed to others; in Ayanz’s case, it was not even that, but simple oblivion—an oblivion that reflects not on the forgotten man but on those who never remembered him.

Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont (1553–1613) was born in the lordship of Genduláin, near Pamplona, into a family of the lesser Navarrese nobility. He was, by any measure, an extraordinary figure: inventor, engineer, scientist and cosmographer, and endowed, moreover, with remarkable physical presence and strength—at least if we trust Lope de Vega’s portrayal in Lo que pasa en una tarde, where he casts him as a new Alcides, a new Hercules.

At fourteen he entered the service of Philip II’s court. Destined for a military career, he took part in the campaigns of Tunis and La Goleta (1573), and was subsequently posted to Milan, where he remained for several years and immersed himself in the scientific developments of the age. He marched with his tercio along the Spanish Road towards Flanders, distinguishing himself as a military engineer in various engagements—Gembloux, Zierikzee, and others. Back in Spain in 1579, he joined the Portuguese campaign the following year and distinguished himself by uncovering and thwarting a French plot to assassinate Philip II. In 1582 he fought in the naval battle of Isla Terceira. Even in 1589 he raised a troop to go to A Coruña to repel Drake’s Counter-Armada.

Soon afterwards (1587), he was appointed municipal councillor of Murcia and undertook the fortification of the port of Cartagena. That same year he was also named Administrador General de Minas del Reino (General Administrator of Mines of the Realm). He travelled across the Peninsula inspecting mines and nearly died from toxic gases released during one inspection. He set about improving the dire conditions in which miners laboured. The two great problems were water accumulation in the galleries and the corruption of the air. To drain the water, he devised a siphon with a heat exchanger: using water from the upper level, with which the ore was washed, he generated the energy needed to raise the water collected in the lower galleries by means of steam driving the fluid through a pipe and emptying the flooded shafts. In doing so he put into practice the concept of atmospheric pressure half a century before Torricelli, and fluid dynamics before Bernoulli; he had invented the steam engine. To tackle polluted air, he cooled air with snow and channelled it into the galleries by the same method. Being the cold air denser, the cooled air lowered the temperature and introduced breathable fresh air, expelling the foul air to the outside. It was the first principle of thermodynamics applied two centuries early, and the first air-conditioning system in history—implemented in the Guadalcanal mine and, on a domestic scale, in his own home.

In 1599 he proposed to the court of Philip III a plan to liberalise the rigid economic system governing mining and labour, alongside a programme to establish schools of mining engineering. These proposals were rejected, though it is unclear whether because they were not understood or because they were understood all too well; modernisation and science were already falling out of favour in a Spain increasingly withdrawn into itself.

Soon afterwards—perhaps sensing that the situation offered no further prospects—he withdrew from public life and devoted himself to operating the silver mine of Guadalcanal (Seville) and a gold deposit near El Escorial.

The list of his inventions, steam engine aside, is astonishingly long. He built successfully tested diving equipment, a compression pump, a furnace for distilling water aboard ship, precision balances, a compass indicating magnetic declination, the arch structure for reservoir dams, furnaces for metallurgical work… As many as forty-eight inventions appear in the ‘Privilegio de invención’, the patent register of the time—many of them one or two centuries ahead of later developments in England during the Industrial Revolution, where they received far greater support and continuity.

The National Library holds a multi-page document, printed in 1612, in which he explains his scientific experiments—accompanied by a letter addressed to Emmanuel Philibert of Savoy—including treatises on the compulsion of elements, the existence of the void, perpetual motion, the sphere of fire and the fall of bodies. He even designed a submarine, though its mechanism remains unknown; he may even have built and piloted it himself, though this point is unconfirmed.

He died at sixty in Madrid, on 23 March 1613, probably from poisoning contracted in a mine. He was buried in Murcia Cathedral. Neither his achievements nor his legacy found any real continuation. Had his programme of engineering schools been adopted, matters might have taken a very different turn—and Spain might never have needed to justify its scientific drought with that boastful retort: “Let them invent!”

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons