- Science

- 17 de December de 2025

- No Comment

- 7 minutes read

ITER: The great international experiment towards nuclear fusion

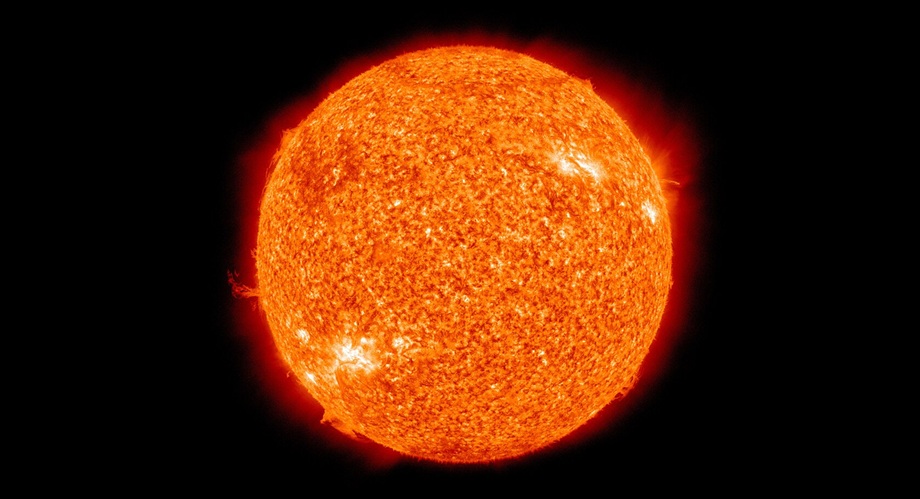

The Sun is a main-sequence star and therefore generates its energy through the nuclear fusion of hydrogen nuclei into helium. At its core, it fuses around 620 million metric tonnes of hydrogen every second. / Photo: NASA_Wikimedia

History, current status, challenges and global competition in the race for the energy of the future

The search for a clean, safe and virtually inexhaustible source of energy has led humanity to explore nuclear fusion, the process that powers the Sun and the stars. At the centre of this endeavour stands ITER— “journey” or “path” in Latin—the largest international scientific experiment designed to demonstrate the viability of fusion as an energy source. ITER is not only a landmark in technological development but also a symbol of global cooperation at a time of growing energy demand and escalating accelerating climate change.

Fusion power plant concepts rely on achieving plasma confinement under conditions where fusion reactions can take place. Two principal approaches exist: Magnetic Confinement Fusion (MCF) and Inertial Confinement Fusion (ICF). ITER uses an MCF device known as a tokamak, first proposed in 1950 by Soviet physicists Andrei Sakharov and Igor Tamm, based on a toroidal vacuum chamber.

The origins of ITER can be traced back to the Cold War. In 1985, leaders of the Soviet Union and the United States proposed a joint initiative in fusion research, building on the Soviet tokamak design and inviting Europe and Japan to join. Over subsequent decades, the initiative evolved into a full international consortium that now includes 35 countries, among them the European Union, China, India, Japan, Russia, South Korea and the United States. The formal agreement to construct ITER was signed in 2006, with Cadarache in southern France selected as the site.

Today, ITER is the largest experimental fusion facility in existence. Construction of the reactor began in 2010. Despite delays and considerable engineering challenges, the project has reached several major milestones. In 2020, assembly of the primary tokamak components began; in 2022, the base of the massive cryostat—the structure that maintains the extremely low temperatures required for the tokamak’s superconducting magnets—was installed. ITER’s principal goal is to achieve a self-sustaining fusion reaction with a power amplification factor (Q) of 10, meaning it would generate ten times the power required to heat the plasma.

According to the current schedule, first plasma is expected in 2034, with deuterium–tritium (D–T) operation—the stage at which full fusion power testing occurs—planned for 2039.

ITER nevertheless faces significant obstacles. These challenges are scientific, technological and financial. From a scientific standpoint, sustaining stable plasma confinement for long durations and managing the extreme heat fluxes and high-energy neutron loads generated by fusion reactions remain unresolved. Technologically, the manufacture and integration of components built from unique materials and designs — true first-of-a-kind systems — require continuous innovation.

Financially, the project has exceeded its original budget, which has drawn criticism and putting pressure on the project to meet deadlines. The need to coordinate the industrial and scientific contributions of 35 member states also introduces significant complexity in project management, logistics and technology transfer.

Although ITER is the largest and most prominent fusion experiment, it is far from alone. The race to achieve ignition—the point at which a fusion reaction becomes self-sustaining in energy terms—has attracted major national programmes and private-sector investment, resulting in intense global competition:

- China: The EAST (Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak) device has achieved record plasma temperatures and confinement times. China is also developing the CFETR (China Fusion Engineering Test Reactor), designed as both a testbed and a commercial-scale demonstrator.

- United States: The National Ignition Facility (NIF), an ICF experiment, achieved the world’s first fusion experiment with net energy gain in 2022. Meanwhile, companies such as TAE Technologies and Commonwealth Fusion Systems are exploring innovative approaches.

- United Kingdom: The Joint European Torus (JET) has been a pioneer in fusion research. The company Tokamak Energy is developing compact alternatives, while the STEP programme (Spherical Tokamak for Energy Production), led by the UK Atomic Energy Authority, aims to build a prototype fusion power plant by 2040.

- Japan, South Korea and Russia: all of these countries are developing their own programmes and experimental reactors, making a significant contribution to global progress in nuclear fusion.

- Within the European Union, additional initiatives include the Euratom Research and Training Programme, Horizon Europe, and several legislative frameworks supporting research, innovation and technology development.

In this context of intense international competition, ITER stands as the most ambitious and collaborative attempt to demonstrate that nuclear fusion could transform the world’s energy systems. Although the challenges are considerable, success at ITER would open the path to future commercial fusion plants and bring humanity closer to harnessing the long-sought “energy of the stars”. The outcome of this race will shape not only the future of energy technology but also global energy security and the planet’s climate trajectory.

___

This article reflects the views of the author. Fusion for Energy accepts no responsibility for any use that may be made of the information contained herein.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons