- HumanitiesIT HAPPENED

- 17 de February de 2025

- No Comment

- 6 minutes read

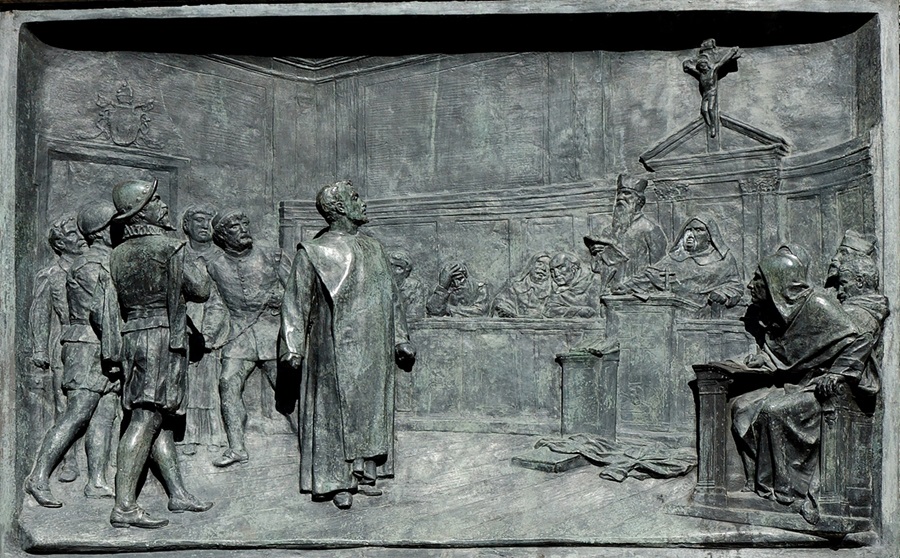

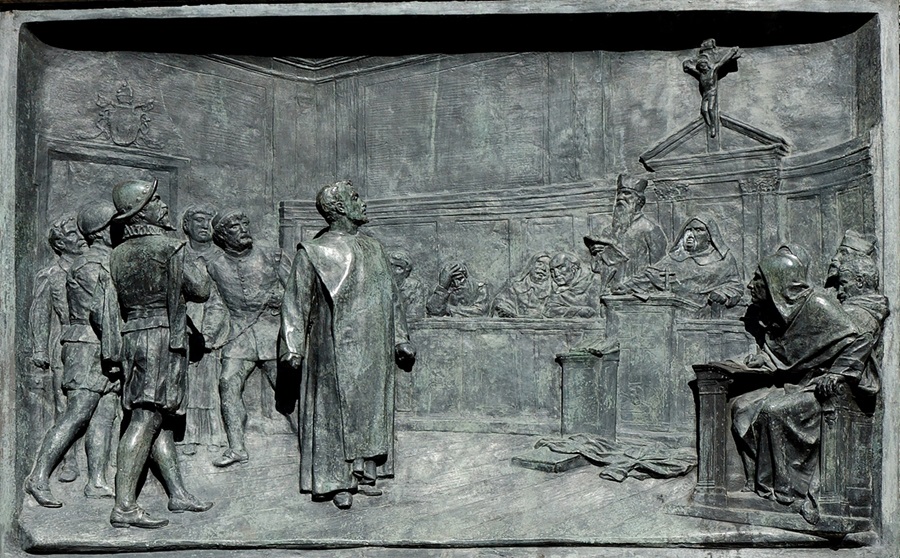

Giordano Bruno

IT HAPPENED…

On February 17, 1600

Giordano Bruno was burned alive in Rome’s Campo de’ Fiori

Four hundred an twenty-five years ago, on February 17, 1600, Giordano Bruno was burned alive in Rome’s Campo de’ Fiori. A genuine representative of the Renaissance “Philosophy of Nature”, he was condemned to death by the Inquisition, accused of blasphemy, heresy and contumacy in spreading heretical doctrines, such as the infinity of the universe, the multiplicity of solar systems or the denial of the Holy Trinity.

He was born in Nola, near Naples, in 1548. At the age of 17 he was ordained as a Dominican friar and from a very early age he caused scandal with his spirited writings and sermons on Trinitarianism, heliocentrism, the plurality of inhabited worlds, the infinity of the universe… Persecuted by the Inquisition, he fled Rome in 1576 and began a life of constant pilgrimage.

Attracted to Calvinism, and perhaps thinking they would receive him better than the Catholic Church -a terrible mistake that almost cost him the stake, as it had cost to Michael Servetus half a century earlier – he travelled to Geneva, from where he had to flee in haste to avoid the “purifying” bonfire to which either Catholics and Reformed were so prone. He went to France, then immersed in the religious wars between Catholics and Huguenots, and was welcomed by Henry II, who allowed him to teach at the Sorbonne. Two years later, he moved to England and taught Copernican cosmology at Oxford.

Always in the risky search for protection from the enemies of his enemies, and from the inevitable precariousness inherent in it, fleeing this time from the Anglicans he moved to Lutheran Germany. In Marburg he held a public debate with professors at the University, during which he was ridiculed, beaten and expelled. He was able to teach at the University of Wittenberg for a short time, but since excommunicated by the Lutherans he had to flee once more.

Finally, he ended up in Venice, which was a place of certain religious tolerance and not prone to theological condemnations. There he became a private tutor to a Venetian nobleman, Giovanni Mocenigo, who, nevertheless, soon denounced him to the Inquisition, “not satisfied with his teaching and annoyed by the heretical speeches of his host.” He was arrested and taken to Rome. He remained in prison for eight years, after which he was sentenced to death by burning.

Actually, Bruno’s influence in the history of thought is due more to his status as a martyr and victim of intolerance and obscurantism than to his real intellectual contributions. In the line of Paracelsus or Telesio, he was not, strictly speaking, a philosopher or a scientist, but a Dominican friar linked to hermeticism who devoted himself to Philosophy, Astronomy and Theology, all of which were quite syncretic and rather in the manner of a preacher. Many of his statements seem common sense today, but his epistemological foundation was rather weak and poorly systematized.

He subscribed to the Copernican system to defend his idea of the infinity of the universe, which he must not have fully understood, since rather than demonstrating it, the Copernican system was a built on the implicit assumption of the infinity oh the universe. He considered the Sun to be simply one more star among infinite solar systems with planets inhabited by intelligent beings. His theological and philosophical doctrine is known as Pantheism, a cosmological conception according to which, to put it briefly, God and the universe are one and the same, at least in the sense that God is not an entity separate from his creation, but rather the creation itself. For Christianity, and for monotheism in general, pantheism is a form of atheism.

As a curiosity, certainly somewhat sinister, let us say that the inquisitor who took Bruno to the stake was the Jesuit cardinal Roberto Belarmino (1542-1621), the same one who years later would initiate the trial against Galileo, although in this case fate – or divine providence – prevented him from participating in the sentence: he died 12 years before being able to see the result of his efforts; although this dis not prevent, as posthumous rewards, his canonization in 1930 by pope Pius XI – we shoud not be surprised about, ir was not so unusual, the Orthodox Church also did the same with Cyril, the instigator of the stoning and death of Hypatia of Alexandria-. In turn, Paul VI established in 1969 the cardinal title “Saint Robert Bellarmino”, one of whose holders was, before becoming Supreme Pontiff, Jorge Mario Bergoglio, the current Pope Francisco.

Bruno was not so lucky, his posthumous title had to wait almost three centuries. On june 1889, a statue was erected by international subscription at the place of his death, at the Campo de’ Fiori, in Rome, exalting his figure as a martyr of freedom of thought.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons