- Face to face

- 19 de January de 2026

- No Comment

- 16 minutes read

Francesc Torralba: “Nowadays, among university students, it’s all simple sentences”

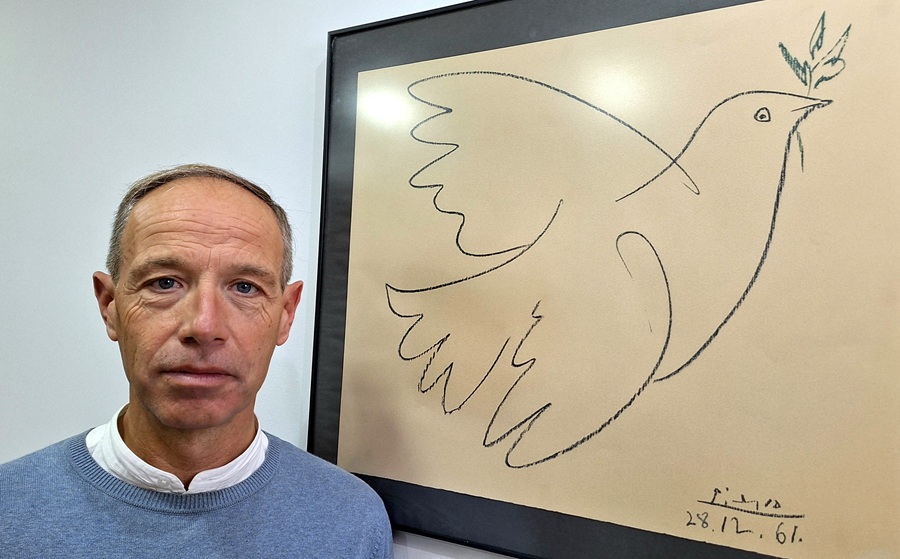

Francesc Torralba / Photo: Courtesy of the author

FACE TO FACE WITH

Francesc Torralba, senior professor of Philosophy at URL. Premi Josep Pla 2026

This past Three Kings’ Night, Francesc Torralba Rosselló was awarded the Premi Josep Pla. Yet the full measure of the man can hardly be captured by a single prize. Born in Barcelona on 15 May 1967, what followed was the emergence of a towering human presence. Professionally, intellectually and morally, speaking with him feels like entering an endless cosmos of values and knowledge. From a very young age, he was drawn to the great questions of human existence—an impulse that led him to philosophy, theology and history. He earned his PhD in Philosophy from the University of Barcelona in 1992, followed by a PhD in Theology from the Faculty of Theology of Catalonia in 1997, with further doctorates still to come.

He later broadened his academic training with doctoral studies in Education (2018) and in History, Archaeology and Christian Arts at the University Ramon Llull (2022). He is currently a senior professor of Philosophy at the University Ramon Llull, where he teaches across various undergraduate degrees and master’s programmes in the humanities, ethics and communication. He also directs the Càtedra Ethos d’Ètica Aplicada (Ethos Chair of Applied Ethics) and the Càtedra de Pensament Cristià del Bisbat d’Urgell (Chair of Christian Thought of the Diocese of Urgell), and plays an active role in ethical reflection bodies both within the university and across civil society.

He has published more than a hundred books and thousands of articles on subjects ranging from the meaning of life and freedom to ethics and anthropology. He has also translated and studied the work of central figures such as Søren Kierkegaard. On a personal level, his career reflects a deep commitment to education, research and the transmission of knowledge. He has received numerous distinctions, including the Joseph Ratzinger Prize in 2023, among other honours that we will gradually unpack throughout this interview. Truth be told—and speaking as an atheist and a scientist—listening to this giant of knowledge and Christian moral thought has left a deep impression on me.

What does SOS Children’s Villages mean to you?

It means that I have been fully and voluntarily committed to this organisation for the past twenty years. They contacted me to explain their volunteer work and initially asked me to provide training for the educators working in the eight villages across Spain. I visited them all and fell in love with both their project and their organisational culture. In the end, I wrote a book for them entitled Esos valores que nos unen, in which I explored the organisation’s core values in depth.

What were those values?

There were four: trust, responsibility, audacity and commitment.

Values that seem to have eroded within our education system. You are now vice-president of SOS Children’s Villages here in Catalonia. Why?

Because we care for children and adolescents in situations of vulnerability who, for one reason or another, lack parental support and are referred to us by the regional government. We accompany them until the age of eighteen. But when they turn eighteen, many still have neither a job, nor the necessary knowledge, nor the skills required for independence. That is why we run what we call “training flats for adult life”, where they can learn a trade and gradually become autonomous.

Yet most people know you less for your voluntary work than for your professional and intellectual activity. Why do you think that is?

People are multifaceted—like a polyhedron—and sometimes one face eclipses all the others. In my case, some know me as a university lecturer; others for having written a doctoral thesis on the Façade of Glory of the Sagrada Família; others for my work on Søren Kierkegaard; and others for having written a book about running. I run every day, I’ve completed marathons, and I wrote a book called Córrer per pensar i sentir (Running to Think and Feel). Some people know me better for that book than for my philosophical or theological work. Defining a person by a single feature is merely a label: you only see the tip of the iceberg, never what lies beneath.

“People are multifaceted, and sometimes one face eclipses all the others”

So, what lies beneath your iceberg? How did you experience the process of completing several doctorates in Philosophy, Theology, History and Education?

I completed my first doctorate in 1992 and the most recent in 2022. Quite simply, I have been drawn at different moments to different fields of study, each of which required intense focus, mastery of the critical literature and, above all, humility—because every doctoral thesis is ultimately a public examination before a panel. A thesis forces you to acknowledge that you are still a student. In fact, I believe a professor should never lose that condition.

Why?

Because many people observe and assess you, and that keeps me alert: it pushes me to deepen my knowledge, sharpen my arguments and improve how I communicate them.

You have become an international authority on Søren Kierkegaard. What can this philosopher offer us today?

A great deal—an extraordinary amount. Above all, something fundamental: the value of authenticity, of being oneself, of resisting mimicry and the uniformity of the masses. If there is a key concept in Kierkegaard’s thought, it is what in Danish he calls enkeltheden: individuality—the fact that each of us is unique, unrepeatable, never before seen in history and never to be seen again. And yet we live like clones, like a herd, endlessly imitating one another. Kierkegaard makes a radical defence—right to the marrow—of the singularity of every person.

“Kierkegaard makes a radical defence of the singularity of every person”

In other words, while some urge us to remain within hegemonic thinking and the dogmas of the day, Kierkegaard would tell us to flee—from pedagogism, for example.

We must flee from the unspoken rule that “this must not be said”. Kierkegaard urges us to abandon the motorways of dominant thought and take the mountain paths instead. That is risky, certainly—but intellectually it is deeply stimulating, because it takes us into uncharted territory.

Faith speaks of dogma, and I know you are a believer. How, then, can faith and science be reconciled?

First of all, we must understand that science and faith are two distinct languages and should not be confused. A person of faith must remain silent on scientific matters and refrain from encroaching on that terrain. Historically, there have been many incursions, invasions and attempts to colonise domains that did not properly belong to one’s own field.

“A person of faith must remain silent when it comes to scientific matters”

As the evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould argued, conflicts do not arise because science and religion are intrinsically at odds, but when one tries to occupy the space of the other.

Exactly. The problem arises when boundaries are overstepped. A theologian, for instance, should not pronounce on what the world is made of. That is not their remit. But a theologian can legitimately ask what we may hope for from God or what the meaning of life might be. Likewise, some scientists venture into territory that lies beyond the scientific method. In short, there are excesses on both sides, often driven by an inability to move beyond literal readings of biblical texts.

You have been a consultant to the Dicastery for Culture and Education of the Vatican that is, of the ministry of the Vatican City State within the Roman Curia, since 2011. What changes do you expect from the new Pope Leo XIV in terms of doctrine?

Within the dicastery we meet to reflect on emerging global issues, particularly those the Pope asks us to consider. This Pope—who is a mathematician, a theologian and a doctor of canon law—is paying close attention to artificial intelligence, something he has already highlighted in several speeches. I believe we can therefore expect a Pope deeply concerned with contemporary challenges in a technological context. We are all increasingly techno-dependent—if not outright techno-addicted—which makes a renewed emphasis on humanism all the more necessary.

“This Pope—who is a mathematician, a theologian and a doctor of canon law—is paying close attention to artificial intelligence, something he has already highlighted in several speeches”

Do you anticipate significant doctrinal changes under the new Pope?

At the level of doctrine, I honestly don’t know. I don’t yet know this Pope well enough, and it would be premature to speculate. My sense is that he is a worldly figure, familiar with both the Global South and North, and not confined to a closed curial mindset. I expect continuity with the reforms of the previous Pope, though with his own personal style—one in which artificial intelligence will clearly feature.

A solid academic grounding among teachers seems essential if knowledge is to be communicated rigorously yet accessibly. You combine university teaching with public outreach and writing. How does academic formation contribute to this?

It is decisive. The problem is that academics sometimes remain enclosed within the university perimeter, treating it as a comfort zone. I have always felt a vocation to step outside the classroom, the library and the seminar room in order to transfer knowledge beyond those spaces.

Through which channels?

Through books, articles, social media, podcasts and the press—anything that allows knowledge to circulate beyond the university walls. I believe there can be no robust democracy without democracy in knowledge. The democratisation of knowledge is an Enlightenment imperative dating back to the eighteenth century. Enlightenment thinkers recognised that knowledge was locked away in Latin and needed to be translated and gathered in what became the Encyclopédie. Today, literacy and the democratisation of knowledge remain essential, which means translating specialised knowledge into language accessible to the majority. Some authors use terminology so cryptic that their work becomes a kind of esoteric code understood only by initiates. This debate—how to make science, philosophy, art or literature reach beyond academic boundaries—is fundamental. As Kant rightly said, a people without enlightenment is little more than a toy in the hands of a despot.

“Populism runs rampant when an uninformed mass swallows everything whole, but it is checked when it encounters communities that think and read”

Are we talking here about pedagogism, extremism or populism?

Populism runs rampant when an uninformed mass swallows everything whole, but it falters when it encounters communities that read, reflect and think critically. That is why those of us in academia cannot retreat into our ivory towers, treating them as oases of comfort while the world outside is falling apart.

Your work focuses on philosophical anthropology and ethics, areas that call for deep reflection. If you had to choose, what matters more to transmit to students: academic knowledge or ethical values?

I would prioritise values such as audacity, resilience, perseverance and tenacity. I take a very stoic view of austerity in desires, because our students will face extremely adverse circumstances in the future. Without certain values, they simply will not cope. Today we see teachers and students who fall apart at the slightest difficulty. How, then, are they to carry forward their life projects without these virtues? Every project encounters setbacks. Values and ethics are fundamental—without diminishing the importance of knowledge.

And what role does knowledge play at university level?

At university level, with a competent and knowledgeable teacher acting as a compass, students can acquire knowledge provided they are taught how to search for it properly—using reliable sources—amid the vast and constantly shifting sea of online information. The professor’s task is to bring those sources closer and help students interpret them correctly.

“Cultivating memory is essential; without it, imagination cannot develop”

Should students memorise knowledge?

Absolutely. Without memory, imagination withers. How can you expand your knowledge or your language if you don’t memorise words? Otherwise, your speech grows increasingly impoverished. When students memorise poetry by Espriu, Carner, Papasseit or Maragall, they expand their semantic range and linguistic resources, enabling them to express thoughts, ideas and desires more effectively. Today, among university students, everything is reduced to simple sentences—and encountering a subordinate clause feels almost like an academic distinction.

Name three essential qualities of a high-quality education system.

First, the universality of knowledge—something that has improved dramatically over the centuries. In the past, knowledge was reserved for elites who could afford it, while the rest relied on charity, often from religious organisations.

The Piarists, John Bosco and others…

Exactly. Second, education must teach people how to think—not in the sense of privileging philosophy, but of cultivating reflection and the ability to construct one’s own life project through texts, classics, films or other sources. And third, people must be taught to express themselves clearly and correctly, both in writing and orally—feelings, arguments, desires and ideas alike.

In summary…

Universality of knowledge, cultivation of thought, and mastery of expression. And this is precisely what is failing.

Given the drastic reduction of philosophy and science hours in schools, what training in ethics and philosophy is essential for future teachers?

Every teacher needs a basic grounding in philosophy and ethics to ensure respectful, high-quality relationships and to prevent abuse, despotism and mistreatment. Ethics must act as a safeguard against these practices. Teachers must also understand their students through anthropology—that is, through knowledge of the human person. I firmly believe that anthropology should be a transversal subject in all teacher-training faculties. Teachers work with people; understanding human nature allows them to anticipate reactions and behaviour. A teacher is not a friend; a teacher is not a colleague. There is still a great deal of ignorance about human nature in education.

“A teacher is not a friend, nor a colleague. There is still a great deal of ignorance about human nature in education”

Should teachers also master their subject matter?

Of course. Whether teaching geology, Catalan or philosophy, a teacher must know their field thoroughly in order to know what to teach.

Thank you for your time. Finally, could you tell us about your latest book. What is it, and what new insights will it offer?

My latest essay, published by ARA Llibres, is entitled La Paraula que em sosté: meditations of a theologian in times of mourning. It forms part of a cycle of reflection on grief, following on from a book published a year earlier, No hi ha paraules, which addressed the inability to find words for the pain and emptiness left by the death of my son.

Does the tragic accident your son suffered two years ago find deeper meaning in this book?

In this book I explain how certain biblical words have brought me consolation, balm and even hope. It is a work of free interpretation. There is not a single text from the Magisterium, the Pope, or any saint. It is a dialogue between God and myself, almost in a Protestant sense. These texts have given me great peace and promise hope. They are familiar texts, but after such an experience they acquire a radically different meaning. They are the WORD—written in capital letters—that sustains me. I merely bear witness for readers to where I have found refuge.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons