- Humanities

- 21 de June de 2024

- No Comment

- 16 minutes read

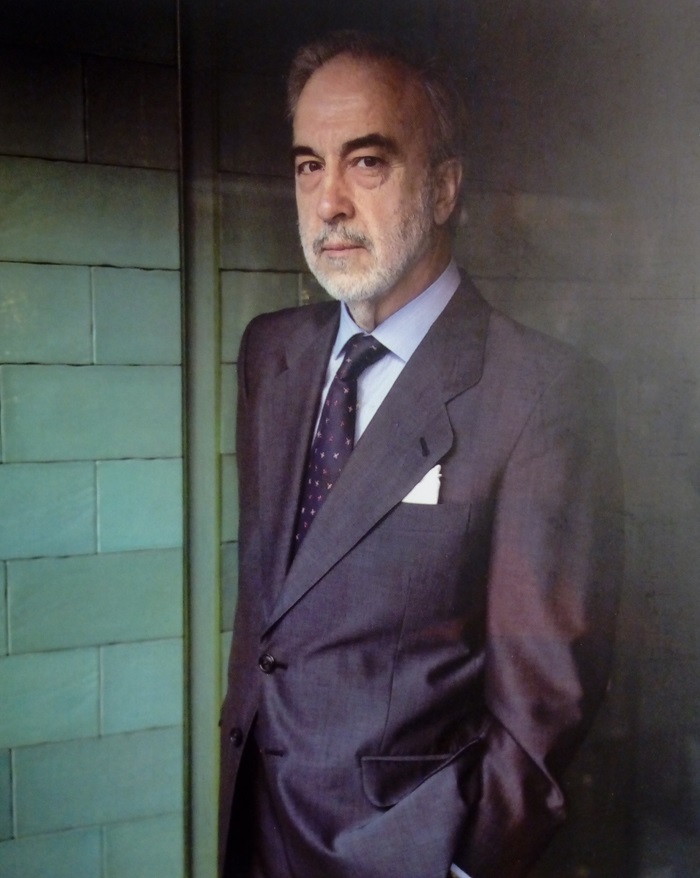

Fernando Castillo: “Looking to past models to analyse the present is as futile as it is inaccurate”

Fernando Castillo:

Fernando Castillo: “Looking to past models to analyse the present is as futile as it is inaccurate”

Fernando Castillo, a wandering essayist and remarkably cosmopolitan figure, with a trajectory so broad that it would not fit here, has recently unveiled Explorador de bulevares (Renacimiento), a collection of literary vignettes portraying cities and a sentimental geography—undoubtedly one of his most personal and conceptually intricate works to date. This exquisitely crafted book commences with the words: “This book is the result of seeing and remembering, but above all imagining some cities and places, seeking simultaneously what they were from what they are and what they suggest”.

How did the idea of creating something akin to a catalogue of city souls come about?

The city, as a space that intricately weaves together the present and the past—so vividly alive it almost feels tangible—has always held a profound fascination for me. It serves as a stage for both objective observation and subjective interpretation. The outcome is a vision of the city imagined, transforming urban landscapes into dreams, as Ernst Jünger suggested—entities born from literary and cultural reimagining. Over time, I gathered writings about various cities, some known and others, the majority not, that had always intrigued me for various and above all imprecise reasons, allowing for a literary reverie of mental reconstruction, sometimes based solely on what literature reveals. For instance, the section “Essential Geography,” featured in both Atlas Personal and Explorer of Boulevards, is a brief chapter, a literary experiment akin to a telegram or postcard, blending greguerías, haikus, aphorisms, or prose poems—an attempt to convey the essence of what certain cities evoke.

What is “Steinerian sympathy”?

We might define it as the particular allure certain places possess, uniquely harmonizing interests and emotions, as George Steiner observed, after experimenting it. It remains a mystery why some cities evoke such strong intellectual and sentimental emotions and closeness, while others do not—a phenomenon reminiscent of human connections.

“It remains a mystery why some cities evoke such strong intellectual and sentimental emotions and closeness, while others do not—a phenomenon reminiscent of human connections”

This sympathy is perhaps a manifestation of the proximity and connection with places that may seem dissimilar and sometimes lack objective qualities to explain such attraction.

You frequently mention Karl Schöghel. Who was he?

Karl Schöghel is among the emerging historians in Europe, hailing from Germany, who have recently focused on the history of Mitteleuropa and Russia with modern and comprehensive approaches. Two of his notable works, one on the Moscow Trials in 1937 and another on Ukraine, provide valuable insights into European reality from both cultural and political perspectives and are highly engaging.

In which city featured in “Explorer of Boulevards” would you choose to live, and why?

Paris or Rome, due to their cultural and personal significance to me. In both cities, as well as in Biarritz, Tangier, or Palermo, I feel a sense of belonging that’s hard to explain. With other places, that feeling simply isn’t there.

How did you become interested in Robert Brasillach and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, significant figures from occupied Paris, a period you’ve extensively researched?

Occupied Paris, now a topic of fascination, offers an exceptional lens into the events of those tumultuous years from 1940 to 1944. In that dark era, it seemed that all boundaries were broken, within a Paris still radiating remarkable cultural richness while morality became more flexible than ever. The intrigue of the Occupation, both literary and malevolent, persists due to the presence of ambiguous and controversial figures like Drieu La Rochelle and Brasillach, arguably the only two truly fascist writers in France, alongside Lucien Rebatet.

Drieu, a veteran of the Great War, witnessing the world’s transformations through stages of avant-garde and communism, eventually embraced a fascist Europe under German influence after navigating nuanced nationalism. Brasillach, younger and drawn to National Socialist ideals early on, succumbed to the weight of nationalism, particularly Maurrassianism and Barresianism, despite being deeply tainted by anti-Semitism. Both were prominent figures whose stars dimmed violently during the Occupation, where confusion and opportunity overshadowed other considerations. Nevertheless, they embody the spirit and reality of a crisis era like few others, if there has ever been one that was not.

Does Modiano play a role in all of this?

Absolutely. Modiano’s work served as the catalyst agent, the guiding light for organizing all the interests and readings that had been accumulating for a long time. His approach to the past in his novels has always captivated and intrigued me. Furthermore, it embodies a methodology, a way of approaching things deeply rooted in French historiography. Modiano’s narrative has the same power to deepen our understanding of the years of the Occupation as the works of historians and writers like Robert Paxton, Pascal Ory, Pierre Assouline, Herbert Lottman, or Henri Rousso.

Do you consider yourself outdated?

I suppose so, and rightly so. However, despite my focus on matters of the past, I remain engaged with everything happening in the world. My past involvement in security analysis and international relations persists. For instance, I’ve been closely following the war in Ukraine since its beginning, keeping a diary that has grown unexpectedly extensive—far more than any of us anticipated for that conflict. Nevertheless, it’s fair to say that I am hopelessly an anachronism in almost everything. It’s a fate that awaits anyone who is somewhat fortunate.

Let’s rewind to the year 2010: Why did the Generation of ’98 hated Madrid so much?

The city, like the rest of Spain, was undergoing rapid change, and most of them didn’t like what was emerging—a modern metropolis characterized by crowds, noise, technology, and politics in the streets. The new modes and behaviours of modernity were displeasing to those who had been born in quiet historic provincial cities, such as Azorín, Baroja, the Machados, Ganivet, or Gutiérrez Solana, accustomed to an old-world environment in their hometowns. The next generation, the Generation of ’14, led by Ramón and Ortega, had a different perspective. They were modernists looking toward Europe through France and Germany, eager for change. After all, Gran Vía represents the street of this later generation, at least in its initial stretch, while the Generation of ’98 remained attached to the historic Calle de Alcalá and Puerta del Sol.

What buildings would you recommend from that rationalist and avant-garde Madrid you studied so diligently?

The work of the architects of the Generation of ’25 and GATEPAC in Madrid represents a sort of exhibition of a new artistic language, serving not only as an approximation to the era but also to contrast the existence of those two cities: the traditional, castiza, majority, with the modern and minority city that emerges in Madrid during the Silver Age. This pronounced duality is one of the defining characteristics of the capital.

To grasp the significance of this modernity, one only needs to mention the Carrión Building, famously known as the Capitol, standing as a true landmark of Madrid on Gran Vía, inaugurated in the significant year of 1936. You can also explore the rationalist colony of El Viso, marvelling at the geometric elegance of its residences, visit the art deco gem Barceló cinema, or discover the more recent Stella swimming pool. There are far more examples of avant-garde architecture in Madrid than commonly believed—one simply needs to look closely to realise it.

“There are far more examples of avant-garde architecture in Madrid than commonly believed—one simply needs to look closely to realise it”

What were your proposals in Atlas Personal (2019)?

Atlas Personal is a unique book for me as it marks the first time I ventured beyond essays into a blend of narrative, essay, and travel literature. It combines current texts with others written years ago, with the oldest dating back to 1974, specifically dedicated to Lisbon during the Carnation Revolution. Most of these pieces were unpublished or circulated only in almost clandestine magazines, so it can be seen as a kind of literary recovery.

Why Tangier? Why Alexandria?

In their own distinct ways, and each situated at opposite ends of North Africa, Tangier and Alexandria are two mythical, exotic cities inseparable from Europe, much like Istanbul. Their rich past, including their 20th-century history, solidifies their status as legendary cities—ones best explored through imagination and literature.

Why Biarritz?

It has been a place where until recently lingered, albeit faded, the remnants of the Europe that once was, allowing glimpses into that profoundly literary past of the belle époque with the ease of the everyday. And I say “has been” because scarcely even the stage curtains of that backdrop remain, lost in the past few decades. Then there’s a personal aspect too, as for years I frequented Biarritz, which brings much closer and explains a lot. It is one of the cities that feels closest to me.

Who was Paul Morand to you?

Like Valery Larbaud and many others of the last century, Paul Morand is a model of a traveller and writer far from exoticism and adventure, which sometimes are merely the froth of travel evaporating into anecdotes. Morand’s approach to places, his perspective, and the way he describes them, but above all what he highlights, reveal a subtlety that always transcends the surface. His book on Venice is exemplary. For intrepid travellers, one might prefer turning to Tintin or Jules Verne rather than recurring travellers to Africa.

Another figure that seems to obsess you is Ernst Jünger, to whom you dedicated an essay in Fervor del acero (2023). Who was he really? What does his life and work suggest to you?

Jünger is an intriguing figure as he combines elements from the past, including those from the Ancient Regime, as well as chivalrous norms that once governed warfare, with aspects of the era in which he lived—the 20th century, which began precisely with the Great War in which he fought. Jünger witnessed and participated in all the horrors of the most dreadful war known to humanity, the emergence of totalitarian regimes, one of which, inadvertently, he served as an initial model. He dedicated remarkable works to these experiences, including his accounts of both world wars, so different in their lived realities, reflections on modern man, the worker as the new man, not to mention his interests in subjects as diverse as bibliophilia, entomology, or philosophy. All of this, and his personality, perhaps not as independent as it seemed, allows him to remain outside of trends but without ignoring them. Then there’s his life, for Jünger is one of those writers whose biography is inseparable from his work, making it hard to determine what is more intriguing, as is the case with T.E. Lawrence, Malraux, or Hemingway. Jünger is inseparable from the 20th century, besides being an author of testimonial works, memoirs, and diaries, extraordinary in their own right.

Do you believe Europe is in danger as it was in the 1930s?

Looking to past models to analyse the present is as futile as it is inaccurate. The conditions of those terrible years for Europe, part of the fiery years that devastated the continent, are unrepeatable, as are those of any era. There may be, and that’s undeniable, some similarities and events that echo the same underlying themes, even echoes, but fundamentally, the European societies of the thirties and those of this century are far from resembling each other. Nevertheless, objective threats are perceivable, such as the existence of an imperialist and aggressive Russia looking more towards itself and the East than towards Europe, a United States turning towards the Pacific, shedding the European veneer that accompanied them since their inception, and nationalist and populist currents exercising anti-European sentiments from within Europe itself. There’s something significant when the far-left and far-right of the continent converge in the same tepidity towards Russia’s imperial and aggressive policies, a regime that stands diametrically opposed to the values that have shaped and currently sustain Europe.

“There’s something significant when the far-left and far-right of the continent converge in the same tepidity towards Russia’s imperial and aggressive policies”

Nevertheless, we must trust in Europe, as it is what truly gives meaning to the way of life we have embraced for centuries as part of it.

What occupies the relentless Fernando Castillo’s agenda now?

To continue doing what I’ve always done. To keep writing and avoiding repetition, which becomes tiresome, and to continue with photography and exhibitions. I have a completed book about a subject so 20th-century as the flight of different characters in their final moments, which I’m revising, and also a shorter, more literary text that I’m eager to finish and revise, as it interests me greatly. It’s a different kind of work, quite advanced already, so much so that I’ve already shared some excerpts in journalistic collaborations and in Explorador de bulevares, specifically one of its chapters. This is perhaps what interests me most at the moment and what I will dedicate my time to.

There’s also a diary covering a year, which is already written and finished, currently sleeping awaiting its moment, if it ever comes, and a chronicle of the war in Ukraine awaiting the end of hostilities, although I suspect I may not live to see the end of the conflict as it increasingly resembles what happened in Korea.

“I don’t reach the performances of Foxá, who would leave a dinner early saying he had to wake up at 11”

Do you sleep?

Yes, very well, fortunately. I don’t reach the performances of Foxá, who would leave a dinner early saying he had to wake up at 11, but waking up early requires an act of will that inevitably leads me to melancholy and unease. I sleep well, indeed.

Do you have a homeland?

Homeland, as that sacred place where nationalism, exclusive preference, and unbridled enthusiasm reside, I’m afraid not. I have never felt belonging to anything with such intensity as what could be considered obedient militancy. Excessive and irrational devotion embarrasses me. Although this doesn’t prevent one from discreetly having enthusiasms and preferences.

Nevertheless, given that homeland is as much a sentimental as cultural matter, arising from where childhood is lived, I would say I’m a European from Spain, something like a “Euroñol,” if you’ll permit the term, albeit a dreadful one. A Euroñol from Madrid, which doesn’t hold much importance.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons