- Literature

- 13 de June de 2025

- No Comment

- 10 minutes read

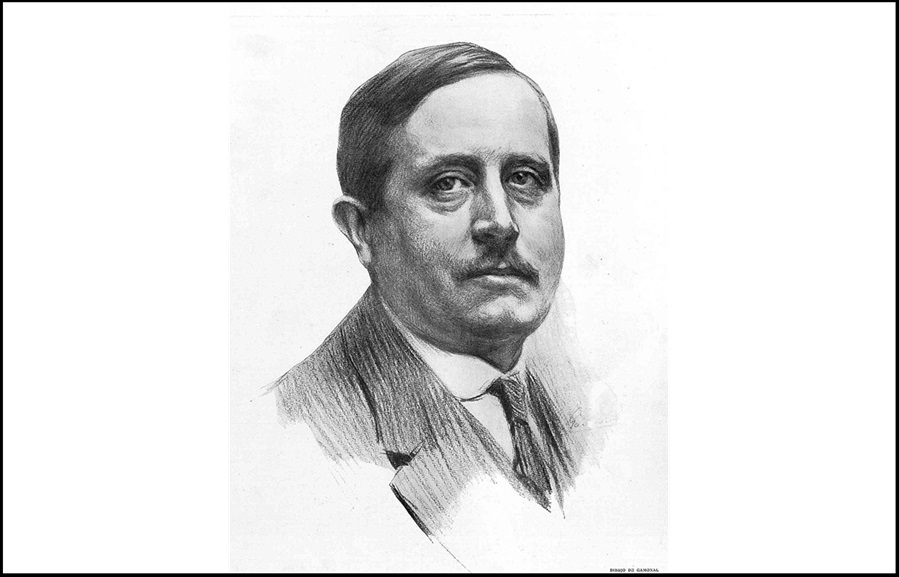

Eugenio d’Ors, Defender of Azorín

Eugenio d’Ors, Defender of Azorín

In May 1915, Eugenio d’Ors published a significant essay in the Madrid-based magazine La Lectura, aimed at vindicating and honouring the literary figure of José Martínez Ruiz, known as “Azorín”. Yet, the essay opens in a distinctly eccentric manner, with one of those characteristic digressions—radical as ever—which function like sleight-of-hand, understood only by the most attentive reader.

The first image presented is a portrayal of Joan Maragall’s study, where two portraits hang: one of Giner de los Ríos, and the other, dedicated, of Miguel de Unamuno. This is followed by an exploration of the Krausism espoused by one of Maragall’s mentors, Josep Soler i Miquel. Why begin here? To trace the embryonic stirrings of Novecentismo classicism present in Maragall’s oeuvre, and by parallel, in that of Azorín, his contemporary:

“No one will comprehend the moral history of Europe in recent times without beginning from the premise that the Nineteen-Hundreds represents a violent reaction against what was called—and rightly should continue to be called by its proper name—‘Fin de Siècle’. Yet much will escape those who fail to recognise that within the ‘Fin de Siècle’ the Novecentismo was already feverishly gestating…”

Thus, the digression serves as a subtle entrée to the core thesis: Azorín, like Maragall, was a proponent of Novecentismo ideals, albeit initially through a symbolist lens. Was this judgement misplaced? It seems not, given Azorín’s subsequent influence on rationalist narrators, ultraist1 poets, and the ramonismo current. D’Ors regards Azorín’s style as one of absolute modernity, purified of romantic haze and post-romantic whimsy:

“In sum, a fresh and delightful manifestation of the same design, a revelation of that ardent cult of light without shadow, of the passion for the living, clear, and bare, of the will—ever alert to perceive, capture and fix the flashes of meaning—is found in the exegetical system of the classics devised by Azorín. He too pricks the thought of the old author he examines, in three or four of his moments of swiftest current, most revealing trajectory”.

D’Ors even goes so far as to consider Azorín a kindred spirit. He aligns Azorín’s precision with his own predilection for miniaturism2, brevity, and conceptismo3 characteristic of his glosas4:

“He too omits—knows how to omit, with supreme economy—the outpouring in which thought slumbers; rather, he spills it anew down an unforeseen slope, where it can most swiftly approach our modern sensibility, refined by the subtlest experiences and stirred by the finest cultures”.

Having just published, Marginal Notes to the Classics, Azorín’s rationalist and succinct methodology deeply resonates with d’Ors, who feels compelled to connect it with Azorín’s distinctive style:

“Those brief texts, which together might fit within a couple of pages—scattered verses, dispersed phrases—expand, acquire broad significance, come to wound us, to work upon us, to unsettle our concerns, our desires, our last-minute passions”.

For Eugenio d’Ors, the Pequeño Folósofo (Little Philosopher) was more than a stylist; he was a thinker. Hence, d’Ors delves into the ultimate meaning behind Azorín’s artistic refinement. The “danger” he perceives in his friend’s criticism is the risk of succumbing to subjectivism: the characters Azorín examines begin to resemble him too closely, since he essentially regards them as mirrors.

How had these two writers arrived at 1915? What preoccupations and circumstances defined them? D’Ors had recently suffered an unjust failure in his professorial examinations in Barcelona in 1914. Ortega and Azorín invited him to Madrid to be honoured and to deliver a lecture at the Residencia de Estudiantes— De la amistad y del diálogo (On Friendship and Dialogue), one of his most memorable and celebrated essays. Azorín had steadfastly defended an Allied stance since the outset of the Great War, whereas d’Ors preferred to portray himself as an unwavering neutralist, though he sympathised with the Germans and espoused a pacifist position, viewing the conflict as a civil war within a single European “Empire”, in which Germany would inevitably take the lead.

D’Ors had sought to transfer (unsuccessfully, due to excessive financial demands) to the magazine España, and attempted to resign from all his administrative posts in Catalonia, failing again as Prat de la Riba—a confirmed Germanophile—refused to accept his resignation. Azorín had, in recent years, shifted towards the conservative right, severed ties with Maura, and publicly acknowledged La Cierva as his patron and benefactor. Many criticised him, arguing that reactionary politics had undermined his rebellious spirit and literary style. Yet d’Ors came to his friend’s defence, writing:

“Why does Azorín sometimes condescend to his detractors by attributing a change of stance to a shift in principle? ‘Yesterday I was a revolutionary,’ the beloved and suffering writer tells us on such occasions; ‘today I am a conservative: such is the work of life upon me…’ Why not say instead: Yesterday I was, and today I am, a man in whom the values of sensibility have become supreme. Injustice and disorder alike offend my sensibility. Tell me one day to express my irritation at injustice; now I prefer to express my irritation at disorder?”.

This insight was later elucidated by the Baroja and Azorín specialist Francisco Fuster in his recent biography of the Alicantine writer.

In his article—actually a series of nine glosas—d’Ors set out not only to vindicate his friend (as his friend had done for him the previous year), but also to renew his own aesthetic proposal, to diagnose the character of an already seminal body of work, and to disseminate Azorín’s philosophy.

Ultimately, d’Ors casts Azorín as a mirror reflecting the virtues of Novecentismo, striving to discern the keynotes of the Alicantine’s oeuvre:

“Exclusive modernity. Nostalgic Europeanism. Love of cultivated nature. Love of elemental labour. Gentle sociability. Epicurean simplicity. Protest against injustice. Protest against disorder…”

Such lengthy and exhaustive orsian essays were unusual. Yet, as ever, his sagacity and capacity for synthesis remain undeniable.

___

1 Ultraist poets were members of an early 20th-century Spanish literary movement called Ultraísmo, which emerged around 1918 as a reaction against Modernism and a response to European avant-garde trends like Futurism, Dadaism, and Imagism. Among its key figures were Jorge Luis Borges, Guillermo de Torre, and Gerardo Diego.

2 A style characterised by brevity and precision.

3 a Baroque literary style characterised by wit, brevity, and conceptual density, often associated with Quevedo.

4 In Spanish literary tradition—particularly as developed by figures like Eugenio d’Ors—glosas are short, reflective prose pieces that combine philosophical insight, stylistic precision, and literary elegance. These texts are typically brief, aphoristic meditations on cultural, aesthetic, or moral themes.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons