- Science

- 27 de January de 2026

- No Comment

- 10 minutes read

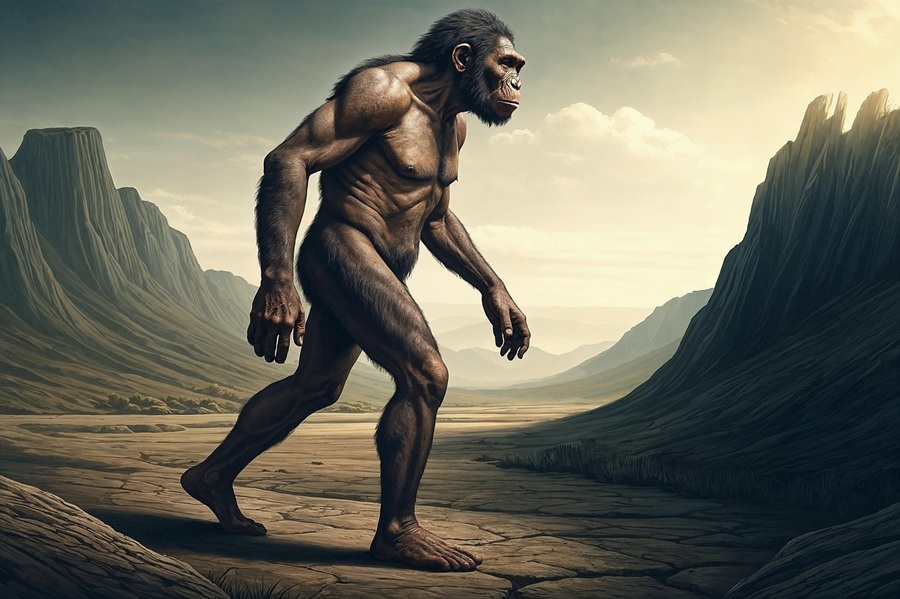

Erectus sex

Photo: Gerd Altmann – Pixabay

We know that in Homo erectus the feedback loop between social cohesion and access to protein improved an organ that is exceptionally costly to maintain: a large brain. We also know that this, in turn, enhanced reproductive success and enabled expansion across several continents. But which biological mechanism made the expansion of the encephalon possible?

If we compare the traits of erectus and Homo sapiens with those of their relatives and other great apes, one crucial fact immediately stands out: their bodies retained increasingly gracile characteristics—that is, increasingly juvenile ones. Adult skeletons came to resemble ever more closely those of juveniles and infants. For instance, if we compare the skull of a human infant with that of a chimpanzee infant, the similarities are striking. As both grow, however, a key divergence appears: sapiens continues to retain juvenile traits, whereas the chimpanzee becomes progressively more robust.

This phenomenon was analysed by Gould in Ontogeny and Phylogeny, under the concept of neoteny. The idea itself was not originally his; he credited Kollmann as its instigator in 1885. Both referred to organisms that, over evolutionary time, progressively retained juvenile—or neotenic—traits. As already noted, the infants of erectus and sapiens were born prematurely in order to pass through the pelvic canal. Had infants grown at the normal rate of other great apes, the brain would have become too large to pass through the pelvic girdle. Faced with the challenge of gestating a large brain, the foetus therefore had to be born earlier, retaining a greater number of neonatal traits. Neoteny in Homo was thus an observable reality.

Another neotenic trait in Homo is the low level of body hair at birth—a relative nakedness that is largely preserved into adulthood. In addition, the learning period in these highly juvenile hominins became extraordinarily prolonged. In short, the evolution of Homo was marked by a pronounced conservatism of juvenile traits through neoteny. This resulted in more gracile bodily structures when compared with their ancestors and with their living relatives, all of whom were far more robust.

Further evidence was provided by McKinney and McNamara in The Evolution of Ontogeny (1991). They introduced the concept of hypermorphosis to describe species that delay development while also retaining juvenile traits into adulthood. One clear example can be observed in the eruption of human molars, which occurs later in Homo than in other great apes. In erectus, molars erupted between four and five years of age, whereas in sapiens this occurs between five and six. Given that in other anthropomorphs molars erupt at around two years of age, it becomes clear that Homo experienced a marked developmental delay, or hypermorphosis.

Another example is provided by the brains of sapiens infants. Although brain growth continues after birth, it does so at a slower rate than in other great apes. In other words, Homo delayed its maturation relative to gorillas and chimpanzees. The ratio between neonatal brain weight and body weight also reflects this pattern. In Australopithecus and other great apes, the ratio is approximately 0.33, whereas in erectus and sapiens it falls to around 0.25. Put simply, Homo delayed cerebral growth during development.

Whether through neoteny or hypermorphosis, the evolution of Homo preserved a large number of juvenile characteristics into adulthood—an essential factor in understanding its major evolutionary gamble: encephalisation. Erectus individuals were born with disproportionately large brains, which continued to develop into adulthood. Neoteny thus reinforced encephalisation. In exchange, infants were born with reduced mandibular, molar and facial structures, which were retained into adulthood in favour of increased cranial capacity. In summary, encephalisation was rooted in the retention of infantile traits, itself linked to a gene that delayed embryological growth through neoteny or hypermorphosis: the ASPM gene.

Once genetics had reinforced this process, erectus continued to develop the full array of neotenic traits that enhanced encephalisation, reproduction and expansion, alongside more efficient resource use, greater social cohesion, and improved defence against predators and competitors. Ultimately, neoteny fostered a higher birth rate in a generalist species. By contrast, their anthropomorphic relatives—chimpanzees and gorillas—became locked into lower birth rates, specialising increasingly in forested and arboreal environments.

Yet erectus did not benefit reproductively from encephalisation alone. Sex played a decisive role in their evolution, as it became emancipated from its exclusive function in fertilisation. In all living great apes except the bonobo, oestrus exists and copulation is therefore restricted to seasonal periods. In Homo and in bonobos, by contrast, there is no oestrus, and sexual activity occurs throughout the year. Without oestrus, males cannot know when their partners are fertile, and sex thus becomes decoupled from fertilisation. This allowed for frequent and pleasurable mating, forging stronger bonds and greater reproductive success.

Copulation therefore no longer served reproduction alone, but also helped to mitigate stress, exchange pleasure and reinforce social ties. Homo was not alone in this respect: bonobos, certain bats and other mammals exhibit similar patterns. It should be added that bonobos, like sapiens, are highly neotenic and capable of face-to-face copulation, among other associated traits. In short, all of them became hypersexual, and in doing so also increased fertility rates under conditions of neoteny. Beyond this, there is another indicator of erectus hypersexuality. In chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans, as well as in australopithecines and Homo habilis, females weighed less than males; overall, males weighed almost twice as much as their mates. These large males competed violently for access to copulation, such that only the winners became sexually active during female oestrus. From erectus onwards, however, the rules changed. As in bonobos, sexual dimorphism between males and females was drastically reduced. Male erectus individuals weighed only around 20 per cent more than females, rather than twice as much as in chimpanzees, gorillas, australopithecines and paranthropines. It is therefore reasonable to assume that, as in bonobos and in most sapiens populations, erectus males no longer routinely competed violently for females. Copulation became less a matter of brute force and more a matter of seduction—though, as always, exceptions to the rule undoubtedly existed.

In summary, erectus evolved towards frequent sexual activity, without alpha males and under conditions of enhanced social cohesion. For the first time in human evolution, sex was decoupled from reproduction and came to provide pleasure and emotional bonding. Most likely, and in the absence of oestrus as a fertility signal, females evolved permanently enlarged breasts and buttocks. These protuberances consist of rounded fat deposits acting as sexual signals. In the past, such traits probably indicated fertility, but in erectus they may have functioned as a form of false oestrus, stimulating copulation.

The female forms that continue to dominate many contemporary conversations and male gazes likely originated with the evolution of erectus. From that point onwards, long and intense orgasms evolved, as did prolonged copulation, increased sensitivity in the penis, lips, tongue, nipples and clitoris, along with other erogenous zones. The brain itself bears witness to this, displaying a septum and an amygdala that are unusually large compared with those of other primates. These two limbic structures help explain both increased sexual pleasure and reduced aggression—key conditions for social cohesion and enhanced reproduction in erectus.

Taken together with cultural evolution, these factors account convincingly for erectus’s reproductive success and expansion across continents. For the first time in human evolution, the remarkable biological and cultural flexibility of erectus propelled the species across four major continents. The brain produced culture, but culture, in turn, reshaped the brain.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons