- HumanitiesLiterature

- 19 de September de 2024

- No Comment

- 12 minutes read

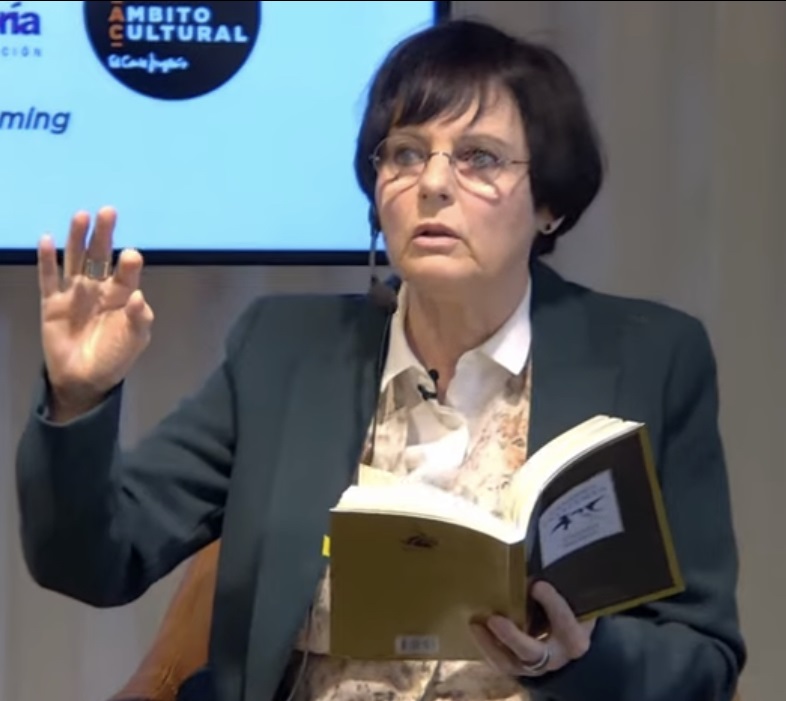

Chantal Maillard: “The poem is something that whispers very softly”

Interview to Chantal Maillard, Philosopher, poet and essayist

Chantal Maillard: “The poem is something that whispers very softly”

Without a doubt, Chantal Maillard (Brussels, 1951) is one of the most remarkable voices in contemporary Spanish literature. She has made significant contributions in poetry and philosophy, earning the National Poetry Prize in 2004. Today, she graciously shares some reflections on her journey.

Why and how did you “kill Plato” in 2004?

It has been 20 years since that attempt. I say “attempt” because it seems it was in vain. That philosopher has a perverse tendency to come back to life. And the problem remains as it was: we live more in ideas—and in images—than in concrete reality. Until death touches us closely, it remains an abstract concept, something that happens to others. Death is a concept, but concepts don’t exist; what exists is what happens: someone dying, or suddenly, not being there anymore. That absence. And even when this happens, we find ways not to fully take it in, devising strategies to shield ourselves from the anxiety. In Killing Plato, someone gets crushed by a truck. Different characters walk by, each reacting in their own way to the event. We all play a part, even you, the reader or listener (I’ve performed this text on stage many times), and of course, the narrator. The fact that we walk past things we think don’t concern us is what allows the atrocities, which we are nonetheless aware of, to continue.

You earned a PhD in Philosophy and specialized in Indian religions at the University of Benares. What are your best memories from that time? What did you fundamentally learn there?

I’m not sure “specialist” is the right word for me. Being deeply interested in something doesn’t necessarily make one special. In my case, my interest stemmed from a curiosity about how the “History of Philosophy”—that is, Western philosophy—began at a particular point in Greek thought. One sentence from Parmenides, conveniently taken out of context, was enough for philosophical inquiry to head West. But what happened before that? Where was the missing link? Thought doesn’t suddenly arise from nowhere at a given moment. Too often, beginnings are marked retrospectively, according to what is deemed important. Since some pre-Socratics had contact with thinkers from northern India, I realized it was necessary to seek out other beginnings in those places.

“«Death» is a concept, but concepts don’t exist; what exists is what happens: someone dying, or suddenly, not being there anymore”

Of course, the way reality is understood in one place differs greatly from how it is understood in another. Crossing borders, one has to travel lightly—not just with baggage, but with the mind. When you approach things openly, you sense and feel through the body more than you learn through words. I learned from the buffalo. Those large black bodies flooding the plains of the Ganges, submerging in its waters, their serene gaze, their slowness, calm, and generous humility. I learned to observe. I learned to be.

Professor Virginia Trueba (University of Barcelona) wrote in 2022: “Maillard’s writing deprograms any logic of genres; it’s a continuous trace that sustains its own variations (as we say about the Goldberg Variations), moving between the conceptual and the existential, the abstract and the concrete, expressing both a desire for calm and a need to scream”. Do you agree?

Virginia Trueba has that rare combination of intelligence and empathy, a quality not always common in academics. I couldn’t agree more with her. As for writing, I believe genre classification is damaging. By directing readers into categories, it eliminates the possibility of crossovers and impoverishes the text. It’s like a doctor analysing a single organ without considering how the whole-body functions. Turning domains into airtight compartments is detrimental to knowledge. The hybridisation of knowledge is, moreover, as necessary as the transgressing genre boundaries.

“No one ‘is’ a poet or philosopher, but rather, for more or less time, is in a poetic or philosophical state”

What is poetry to you? And philosophy?

After what I’ve said, it may sound like I’m contradicting myself. So, I will have no choice but to refine what I’ve said. Poetry and philosophy are indeed very different—at least how philosophy has been understood in the West. The attitude required for each is completely different, even opposite. For a poem to emerge, one needs attentiveness and receptivity. The poet—better said, someone in a poetic state— for what needs to be discussed are states: no one ‘is’ a poet or philosopher, but rather, for more or less time, is in a poetic or philosophical state—the poet, I said, does not search. He is open to receiving. He attends. Philosophy, on the other hand, is an active search, starting from a premise and working toward a conclusion. Philosophy is laborious, relying on logical links, while poetry originates in the body before words. But isn’t the intellect also a body?” you might ask. Certainly. The intellectual process is an activation of the organism, but it is processed in a specific place, whereas in the poem, the entire body is activated, especially the senses, which are never left aside, unlike in the hypothetical-deductive process typical of philosophy (I emphasise: as it has been understood in the West).

In 2020, you gave voice to Medea in a powerful poem. What is most relevant to you about this mythological figure? How did you come to the decision to write about such a controversial character?

It wasn’t a decision; it was a necessity. Empathy—the need to not just understand but to fully step into another’s shoes and to experience their emotions—has been a theme in my writing, especially since Killing Plato. You could say it’s a leitmotif. And not just in poetry, but in my essays as well. In fact, my previous book, The Difficult Compassion, that precedes the collection of poems Medea, deals with the challenge of empathizing with those whose actions are judged as inappropriate, perverse, cruel, or, as in this case, ‘against nature’. It’s much easier to feel compassion for someone we consider innocent according to our codes; that gives us a good conscience. But what’s really difficult is to empathise with someone we judge as guilty. And that’s the issue. Because, if we look closely, we are all guilty as soon as we conceive: we all deliver our children to a certain death, to the unavoidable suffering that life brings, and to the harshness of a world for which we don’t always, or all of us, have resources.

Medea is a figure who, in light of the indispensable need to reduce the human population that this planet requires, could serve as an active symbol, because, evidently, as this secular and wise Medea I’ve wanted to awaken from her hells says, “killing what you love is not something you know anything about”. It’s about women becoming aware that although we can create life, we can also refuse to do so. We can stop procreating, for the good of the planet and all beings that are part of it.

“Life is not only continuity; it’s also discontinuity, rupture, chaos, all of which are necessary for a new order to emerge”

You wrote in La razón estética (Aesthetic Reason) (2017): “Aesthetic laughter assimilates what is unacceptable to ordinary laughter”. Could you elaborate on that?

I wrote that chapter quite a while ago, where I felt moved by the naïveté of the Pink Panther, a character who touched me deeply. I wouldn’t be able to do it better now, nor could I summarise it in a few lines, so to answer your question, I’ll just point out the following.

Aside from the kind of laughter that bursts out from pure vitality (children’s laughter when they run, for example), laughter is originally a reaction that forms part of the body’s defence system. Laughter triggers an increase in the production of endorphins necessary for reacting to danger. Comedians know very well that this happens also when we encounter something unexpected or absurd. To provoke laughter, you have to present a situation in which something suddenly doesn’t fit, breaking the natural continuity of the story. What’s curious is that we can also derive pleasure from these interruptions. Because life is not only continuity; it’s also discontinuity, rupture, chaos, all of which are necessary for a new order to emerge. Pleasure occurs when the tension generated by something seemingly incoherent is released. That tension is, in fact, the same that arises from a metaphor: two disparate elements that fuse or overlap as if to suggest they are similar, when they aren’t, or not entirely. It’s the “as if—but not quite” that activates this metaphorical mechanism. In comedy, however, when the absurd is resolved, the disparate elements don’t integrate; rather, what happens is that the code is restored. Comedy is conservative. Aesthetic laughter, on the other hand, would be the kind that not only accepts the inadequate integration of the dissimilar but also expands the boundaries with it.

In your poem Hilos (2007), you ask: “¿Qué haremos del poema sin metáfora, / del verso despojado de su naturaleza, / de su afición al desvarío y su grandilocuencia.1 So, I’ll repeat the question. What shall we do with it?

Put poiesis (the crafting of the artefact) aside to make way for attentiveness and listen more carefully. The poem is something that whispers very softly, and you need silence to hear it. If the mind is full of words and judgements, it will only project outward what it already knows or thinks it knows. There will be no room for discovery.

What current poetry interests you?

Very little. Perhaps Inger Christensen.

Do you have a reference thinker?

That’s difficult to say. Many have interested me, and very different ones, depending on the period and the topic I was tangled in. If I disregard the sealed compartments and pull from my library, I can recall Camus, Kant, Schopenhauer, Epictetus, Michaux, Pessoa, Deleuze, Nagarjuna, Watzlawick, Bateson, Laozi, Zhuangzi, Quignard, each for a different aspect, among many others. But I must confess that those who teach me the most are the grasses, the cicadas, the mountains, those beings whose language the titan Typhon understood.

What are you working on now?

I’m fine-tuning my listening.

___

1 What shall we do with the poem without metaphor, / the verse stripped of its nature, / of its penchant for madness and its grandiloquence?”

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons