- Opinion

- 18 de December de 2024

- No Comment

- 8 minutes read

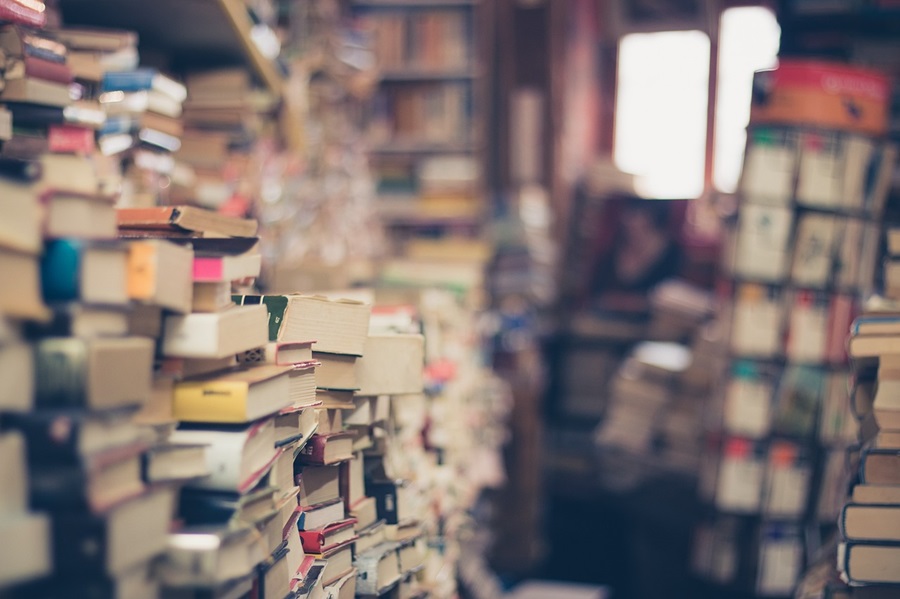

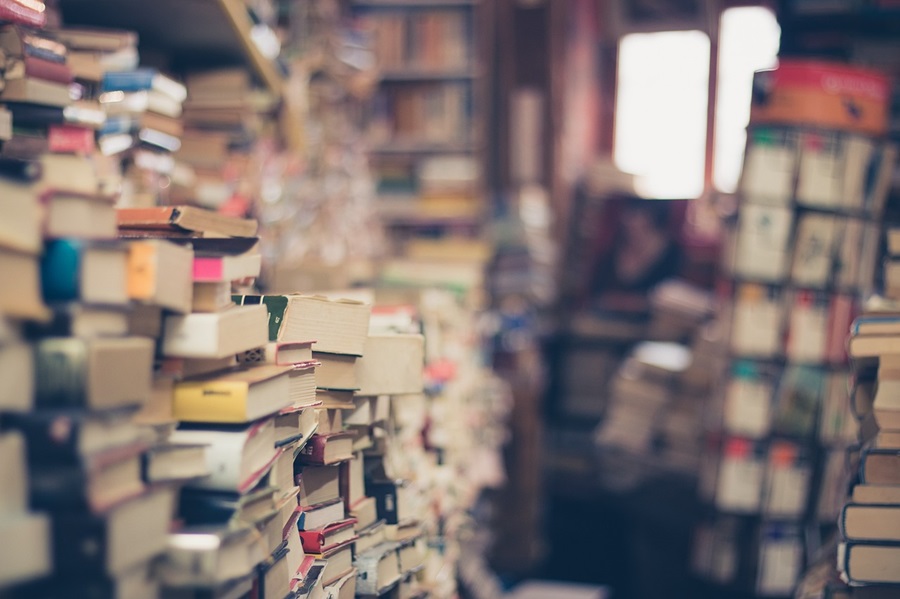

Books Without Readers, a Future Without Citizens

Books Without Readers, a Future Without Citizens

There exists a vast galaxy of periodicals that provide essential insights into understanding the world we inhabit: the social transformations, the uncertainties of technology, the political oscillations. In one such magazine, Mundo Diners, Jorge Carrión observes that the world is increasingly divided between those willing to pay for subscriptions granting access to high-quality “content” and those who settle for free offerings. This shift is significant, as the funding for influential material appears to be concentrating in the hands of those with financial resources, while a sea of micro-subscribers—burdened by scattered interests, high daily expenses, and limited loyalty to the valiant, diverse forms of cultural resistance—struggles to keep pace.

This comes to mind in connection with reading an article by Rose Horowitch in The Atlantic—one of those recommendable periodicals—where she explores the challenges faced by elite American school educators in finding students capable of reading entire books. Her investigation reveals growing concerns about declining literacy and comprehension levels among younger generations. This decline threatens not only their employability—a pressing concern for proponents of an education system tailored to businesses and economic demands—but also their critical thinking skills, as advocated by those of us who continue to believe in a capitalised Education, which must primarily shape future citizens in the most democratic sense of the term.

Horowitch’s findings prompted The Atlantic‘s CEO, Nicholas Thomson, to solicit opinions from Silicon Valley’s pioneers of cutting-edge technology—generative AI being the latest frontier. Their response was startling: books are inefficient tools for knowledge transmission. Silicon Valley possesses superior, more advanced alternatives. That books could be deemed “inefficient” is a perspective I had never considered.

While Horowitch’s piece is well-grounded, its core concerns are not new. In his compelling work Construir lectores (Building Readers), published by Vaso Roto, professor Vicente Luis Mora—whom I confidently predict will join the Spanish Royal Academy alongside Carrión—reminds us that “for any humanist, of any era, each generation appears to suffer a decline in cultural standards compared to its own or the preceding one”. The professionals interviewed by Horowitch echo this sentiment, lamenting that students today struggle to focus even on a sonnet, let alone interpret it.

Among the usual suspects for the decline in reading are screens and social media—an easy and obvious culprit that conveniently allows the case to be closed without further complexities. Mozambican writer Mia Couto, upon receiving the Guadalajara International Book Fair Prize, recently remarked: “The reality delivered to us through a luminous screen is a wall that obscures our humanity”. It was also revealed in these early days of December that Oxford’s 2024 Word of the Year is “brain rot,” a term rooted in internet culture. Wikipedia, citing Oxford University Press, defines it as “the supposed deterioration of a person’s mental or intellectual state, especially viewed as a result of excessive consumption of material (now particularly online content) deemed trivial or unchallenging”. Yet, the roots of declining reading habits and critical capacities among the young may be more complex. Jonathan Malesic, writing in The New York Times, suggests that young people read less as a rational response to the success models they observe: “Productivity no longer correlates with labour, and wages bear little connection to talent or effort”. Influencers and content creators, seem to thrive by sharing personal lives or crafting some original but, above all, viral entertainment.

Vicente Luis Mora provocatively questions whether children’s disinterest in reading is the real issue, or whether the lack of engagement from teachers and parents bears greater blame. The UK’s latest OfCom report on internet usage habits in the United Kingdom (Online Nation Report), in 2024 reveals that adults now spend an average of 4 hours and 20 minutes online daily. Looking at these figures one might wonder how much of that time is spent engaging with their children—likely less than is devoted to Netflix.

The ramifications of this decline extend further. The censorship of books in U.S. schools resembles an epidemic of paranoia, with over 4,000 titles banned, as reported by the American Library Association— all of them in an unjustifiable manner and often many in a completely incomprehensible way. Mora rightly advocates how this medieval fervour can be aligned with the essential need for young people to encounter “age-inappropriate emotions” through literature that challenges their self-awareness. Haven’t we all grown up reading “too advanced” novels and watching films meant for older audiences?

Without such challenges and exposure to content that evolves into enduring “works”, as Carrión emphasises, we risk failing to develop not just readers but autonomous, critically-minded adults equipped with a critical literacy suited to the enormous challenges of contemporary societies and committed to fostering healthy collective coexistence—peaceful, respectful, and inclusive. The death of reading threatens not only books, as books have been the instruments that have allowed for the dissemination of shared values of collective progress, as well as the transmission of accumulated knowledge throughout history. This essential link in the chain of human progress now faces potential extinction.

Yet is it truly endangered? Today, more people read and write than ever—albeit in new formats. Our world is textovisual, as Mora observes, suggesting that the book’s demise may not be as imminent as feared. Horowitch’s article leads us to a delightful piece by Jeff Jarvis in The Atlantic (I Was Wrong About the Death of the Book, September 2023), in which Jarvis retracts his earlier prediction of the book’s demise, a fate he himself had predicted fifteen years ago. Citing Jessica Pressman, he highlights how books have historically symbolised privacy, pleasure, individualism, knowledge, and power. And it is precisely all this symbolic capital that would support Umberto Eco‘s view, rather than his dark and pessimistic prediction. Jarvis also cites a wonderful 2012 piece (Dead Again) by Leah Price (New York Times), which recalls that as early as 1831, Théophile Gautier wrote that newspapers were killing books. This, in turn, leads to another remarkable text from 1992, by Robert Coover (Stand up, readers), titled The End of Books, which identified hypertext as the new real threat to books.

Nonetheless, the outlook is hardly rosy. If we agree on the importance of books beyond entertainment, pragmatism, or self-help, and recognise their social role, action becomes imperative. The alleged inefficiency of books provides a clue to the new threat: the relentless drive for hyper-productivity, dictated by unchecked powers, as Luigi Ferrajoli warns. Discussions about books and readership ultimately centre on humanity—on what distinguishes us from machines and algorithms. Once again, it is time to read to survive.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons