- HumanitiesLiterature

- 6 de June de 2024

- No Comment

- 39 minutes read

Antoni Martí Monterde: “It is not a favourable time for the figure of the Intellectual, yet we need it more than ever”

Interview with Antoni Martí Monterde, author of El falso cosmopolitismo

Antoni Martí Monterde: “It is not a favourable time for the figure of the Intellectual, yet we need it more than ever”

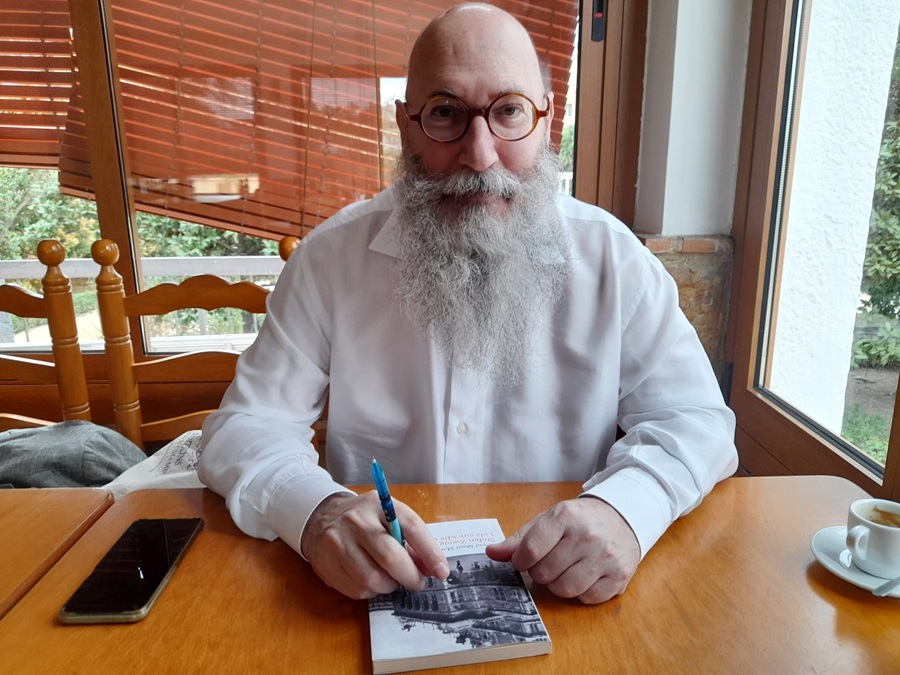

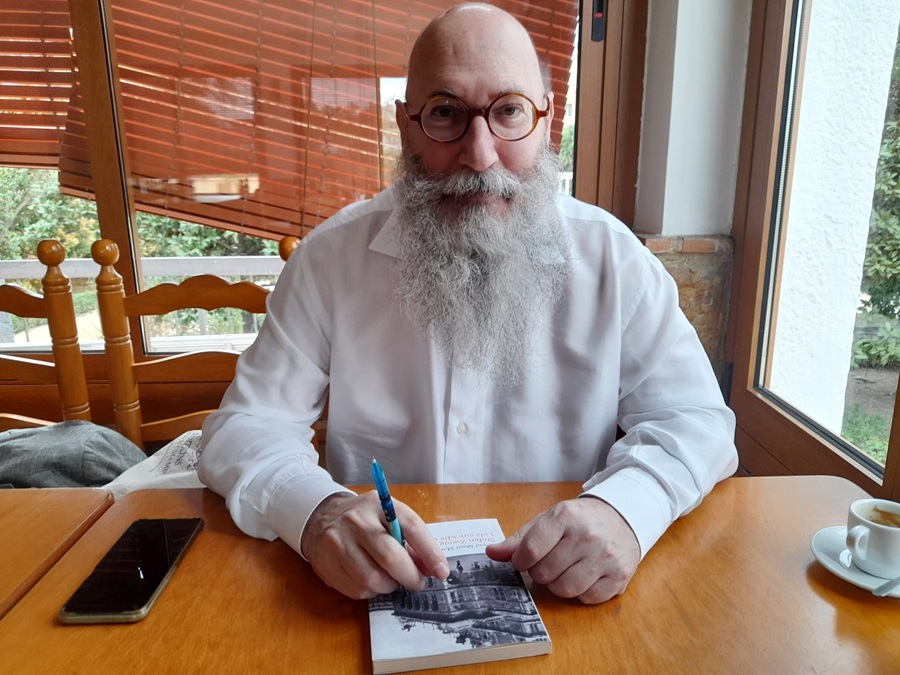

Antoni Martí (Torís, 1968) is a cultural hyperactive. A professor of Literary Theory and Comparative Literature at the University of Barcelona, he has just published El falso cosmopolitismo with the HyO label, which had previously reissued his monumental study Poética del café. Un espacio de la modernidad literaria europea (2021). As an author of an impressive number of studies and books, we review his latest works with him.

El falso cosmopolitismo” is a difficult book to define. What will the reader find in it?

Firstly, more than a difficult book to define, I believe it is unfortunately uncommon to find books with such an approach in our context. Generally speaking, as in the case of Poética del Café, which was also published (reissued in this case) by HyO, it is a book of Comparative Literature and Comparative Intellectual History. To be more specific, it is the intellectual history of Polémica del Meridiano, which begins with the editorial “Madrid Meridiano intelectual de Hispanoamérica,” published in April 1927 in La Gaceta Literaria, where Guillermo de Torre wrote, for example: «Frente a la imantación desviada de París, señalemos en nuestra geografía espiritual a Madrid como el más certero punto meridiano, como la más auténtica línea de intersección entre América y España. Madrid: punto convergente del hispanoamericanismo equilibrado, no limitador, no coactivo, generoso y europeo, frente a París: reducto del “latinismo” estrecho, parcial, desdeñoso de todo lo que no gire en torno a su eje. Madrid: o la comprensión leal –una vez desaparecidos los recelos nuestros, contenidas las indiscreciones americanas– y la fraternidad desinteresada, frente a París: o la acogida marginal y la lenta captación neutralizadora...». (“Against the misguided attraction of Paris, let us mark in our spiritual geography Madrid as the most accurate meridian point, as the most authentic line of intersection between America and Spain. Madrid: the convergent point of balanced Hispanic-Americanism, non-limiting, non-coercive, generous, and European in contrast to Paris: a stronghold of narrow, partial Latinism, disdainful of everything that does not revolve around its axis. Madrid: or loyal understanding – once our suspicions have vanished and American indiscretions contained – and disinterested fraternity in contrast to Paris: or marginal reception and slow neutralizing capture…”). From this editorial, a transatlantic controversy unfolds, lasting decades with multiple ramifications, becoming an axis that clearly illustrates a nationalist drift of Spanish intellectuals, which drags on to the present: that the idea of the Empire must resurge. Therefore, the central concept studied in the book is the idea of False Cosmopolitanism. Furthermore, it has a strange relevance now that there is a sinister resurgence of Spanish Imperialism, and many intellectual impostors from Barcelona and Madrid are enthusiastically joining it. In the book’s conclusions, I highlight a fact with several protagonists: “They await Cervantes, Princess of Asturias prizes, and seats in the Real Academia Española de la Lengua (Royal Spanish Academy of Language); and this has been the case for almost a century. The unity of Spain as an absolute value – as explained by Antoni Simón Tarrés in a book published by Afers editorial last year – is an investment in the short, medium, and long term”.

How did you come across Guillermo de Torre? Why do you consider him an important figure?

All journeys begin in a library and often end in one. When I was studying Philology in Valencia, entrenched in the library and the cafeteria reading authors not included in any subject’s syllabus, I realised that the books that interested me the most had Buenos Aires’ imprint. I began to desire to go there, which I did twice, in 1996 and 1998. In Buenos Aires, I discovered the real Café life and, above all, second-hand bookstores like La Librería del Colegio, next to my hotel and the Plaza de Mayo, created by Antoni López Llausàs, founder of the Catalònia Bookstore and who, like many Catalan intellectuals, had exiled to Argentina. On the shelves of that bookstore, I found many of my favourite authors in editions by Losada, Sudamericana, Sur, Emecé, among many others I did not know, which had probably been there since the day they arrived as new publications. It was as if they were waiting for me.

“All journeys begin in a library and often end in one”

Guillermo de Torre was one of Losada’s editors and the author of a book I had found in a second-hand bookstore in Valencia shortly before leaving my city – I have a habit of signing and dating books when I buy them, and it was on 22 September 1995. Already in Barcelona, precisely while trying to write a doctoral thesis on J. V. Foix, I found Apollinaire y las teorías del Cubismo (1967). Once in Buenos Aires, and especially at the Ross Bookstore in Rosario, I found more of his books: Tríptico del Sacrificio (1948), La aventura y el orden (1941), and Problemática de la Literatura (1951). All this was just a moment of euphoria that turned into a suitcase full of books that, upon returning to Barcelona, began to be arranged as a double shelf: on one side, books by European authors who had at some point in their lives passed through Argentina: María Zambrano, Rosa Chacel, Rafael Alberti, María Teresa León, Witold Gombrowicz, Ramón Gómez de la Serna. Almost all of them acquired during those two trips in 1996 and 1998. On the other side, Café writers, because my discovery of European Cafés was on Avenida de Mayo in Buenos Aires when I opened the door of Café Tortoni.

All of this resulted in the book L’erosió. From those two trips also emerged Poética del Café.

I will ask you about three protagonists of your essays: Joan Fuster, Josep Pla, and Ramón Gómez de la Serna; what do they mean to you?

Let’s start with Ramón, a great Café writer who defined the Café – always written with a capital letter, no matter what the Royal Spanish Academy says – as an institution. I also consider myself a Café man, and anything I could say about them has already been said much better by the author of Pombo. However, everyone has an overly stereotyped image of Gómez de la Serna, associated with laughter, frivolity, and above all, Greguerías. In contrast, he was a very serious writer, a quite misunderstood precursor of the avant-garde in Spain in the 1910s. Above all, he was a Café man. His first autobiographies are, in reality, Pombo (1918) and La Sagrada Cripta de Pombo (1924), that is, the history of the Café where he animated one of the most important literary gatherings in Europe. I had not yet read the Viennese Café authors, so he set the caffeine tone of my writing. However, Ramón, the author of Ramonismo – which authorizes us to call him without his surnames – was also a tragic figure. Exiled in 1936 because he did not know which side would kill him, he settled in Buenos Aires “as if it were forever” without knowing that he would indeed never live in Madrid again. The title of his only explicit autobiography is a clear message: Automoribundia, written in Buenos Aires and published in 1948. It is an exhaustive, exhausting, and sometimes desolate book, like the last ones he published shortly before dying: Cartas a las Golondrinas (1949) and Cartas a mí mismo (1956). They are two terrible books that announce his death almost by starvation. He is a writer who must be reread in this dual key: as a great Café writer, an innovator in European letters, and as a writer of biographies and autobiographies that disrupt self-literature.

I came to Joan Fuster, Josep Pla, and the Catalan language and literature almost simultaneously, but first, I must speak of J. V. Foix, who was my entry not only to Catalan literature but also a turning point in my life, including a change of literary language and political mentality.

I came to Joan Fuster, Josep Pla, and the Catalan language and literature almost simultaneously, but first, I must speak of J. V. Foix, who was my entry not only to Catalan literature but also a turning point in my life, including a change of literary language and political mentality.

As I explained in Paper de Vidre a few years ago in the section “El recuperat,” I proposed to Tina Vallés “L’Estació.” That poem was not only the first I read by J. V. Foix but also the first I read in Catalan. In the nineties, I was a young Spanish-speaking person who was studying Spanish Philology and so, I did not understand it at all. It wasn’t just a linguistic difficulty. I read it in the reduced facsimile edition published in the magazine Poesia in 1985. It was fortunate to read Foix for the first time in the Bodoni typography that Jaume Vallcorba knew how to respect. For me, it was a profound seismic shift that prompted me to change languages and start reading and writing in Catalan. When I spoke and wrote in somewhat acceptable Catalan — though my Valencian friends and later the Barcelonians told me I spoke strangely: in Foixian, and no one understood me at all — I still didn’t understand what the writing was conveying. Yet it continued to captivate me. I even began a doctoral thesis to explain it to myself. It was all in vain. The day I discovered Foix was a point of no return, as if I had broken through the wall of Tocant a mà. According to the signature of that day, It was 26 February 1994, and despite having written a book about his work, I still feel I am grasping what he has to say. And so it will be, I imagine, until my complete disappearance, under a sky of smoke and fog, probably under the double vault of França Railway Station, which for me is L’Estació.

So, I dedicated an entire year to writing a voluntary paper for the Medieval Catalan Literature course on Foix and his earlier influences. This effort led to the creation of the embryo of my first book, J. V. Foix o la solitud de l’escriptura, and also marked a personal decision: I would become a Catalan writer. At that time, I aspired to write poetry, but perhaps due to that initial attempt, I gradually gravitated more towards essays and, later, diaries.

At this point, the reading of Joan Fuster was crucial, also regarding my way of studying literature.

Fuster was, for me, a great professor of comparative reading and a distinguished comparatist. Through reading Fuster, I discovered Michel de Montaigne, Erasmus, Voltaire, Paul Valéry, Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, among many others, including Josep Pla. I learned a great deal from him. Thanks to his Diaries, I began writing my own, and reading Josep Pla — inspired by Fuster — confirmed this daily practice. Interestingly, I didn’t start reading Fuster with Nosaltres els Valencians as it is typical, but with Les Originalitats, which, while not his first published book (that was El descrèdit de la realitat in 1955), is probably the first he wrote. Published in 1956, it includes in the introduction and first part an entire theory of the essay with reflections that also connect with the poetics of Josep Pla’s prose. In 1998, I wrote an introduction for a school edition. However, a year earlier, I presented a paper on Joan Fuster at the centenary congress of Josep Pla held in Girona: “Josep Pla: memòria i escriptura.” My paper was titled “Josep Pla i Joan Fuster: la construcció de l’assaig català contemporani,” and it was the first I published on both.

“The day I won the Joan Fuster Prize with a book about Josep Pla, besides being immensely happy, I realized that I had closed a literary circle that had shaped who I am”

Evidently, the first thing I read by Fuster about Pla was his introduction to the Complete Works, which leads “El quadern gris”. Reading the immense diary of Josep Pla and later other volumes of his work — I confess I involuntarily stole volume XII Notes disperses from the library of the Faculty of Philology at the University of Valencia — was also prompted by Fuster. I explain this in my book on Fuster published by Afers. Shortly thereafter, I discovered Madrid. Un dietari (1929), which also captivated me with how some journalistic chronicles could become so literary. In 1998, I published a text about the book Diaris de dia, diaris de nit. Madrid segons Josep Pla in the catalogue of an exhibition at CCCB. It was the first thing I wrote solely about Josep Pla, and it sparked my curiosity for his travel books and reports. Later, it become the embryo of París, Madrid, Nova York. Les Ciutats de lluny de Josep Pla, which won the Joan Fuster Essay Prize in 2018. While writing it, since I was living in Girona at the time, I spent many Sundays walking in Palafrugell and reviewing the draft at Casino Fraternal, one of my favourite cafés. The day I won the Joan Fuster Prize with a book about Josep Pla, besides being immensely happy, I realized that I had closed a literary circle that had shaped who I am.

Antoni, what on earth is an essay?

As Joan Fuster said, “The perfect essay would be one consisting of a single word, ‘essay’ only, for example”. The etymology of this word conceals a myriad of definitions that kaleidoscopically round out the answer to the question. Jean Starobinski has dedicated significant reflection to it: Known in French since the seventeenth century, derived from the Low Latin exagium, it comes from the verb exagiare, which means to weigh. Alongside this term, we find examen: the needle of the balance to put to the test. Montaigne’s medal alongside the mythical question “que sais-je”? displayed a balance. But examen also refers to essaim, a swarm of bees, a flock of birds, dispersion still linked by the inherent will to integrate and make possible l’essor, the flight. Etymology also, or especially, refers to exigo, to demand, to make something come out, to extract, to pursue. The sense of prouver, éprouver originates in Montaigne’s lands to the south, in Gascon. Thus, as Jean Starobinski concludes, essai implies the pesée exigeante, l’examen attentif, but also the verbal essaim in which one attempts, with the flight of the word, la mise à l’épreuve, una quête de la preuve. “The essay is this, an attempt. An attempt that has had some positive result”, writes Fuster in the prologue of Les Originalitats. On the other hand, the master of all essayists, Michel de Montaigne, drew the clearest line: “With my opinion, I intend to give the measure of my vision, not the measure of things”.

“The essay is the writing of the demon, of the one who dares to say ‘no’ when everyone else says ‘yes’”

But to summarize very concretely, the essay is the writing of the demon, of the one who dares to say ‘no’ when everyone else says ‘yes’. Joan Fuster points out that the strength of a culture depends on the intelligence of the demon. An essay could be defined as this way of looking at reality in writing, against the grain, as Walter Benjamin does with history, and explaining it while explaining oneself.

And what about Cosmopolitanism? I mean the real one.

Cosmopolitanism has various origins, all very classical and interesting. However, it is a concept that, like that of world citizen, has been eroded by its overuse and abuse. Today, when someone proclaims themselves a world citizen, it often conceals a nationalist trying to impose his particular vision of the world on another with whom he has a national dispute — remember the foundational manifesto of Foro Babel or Ciutadans.

There are cosmopolitan people, cities, and societies, but for me, true cosmopolitanism must be intellectual and literary: a reconciliation of Enlightenment principles with Romantic ones. On the one hand, rationalism represents a universal commitment for everyone, but this does not mean uniformity of thought. Each individual and each culture has an irreplaceable contribution to make to humanity as a whole, and in this sense, they are cosmopolitan. A true cosmopolitan should feel at home anywhere, read any literature as their own, and respect the right of hospitality for all.

As Yves Charles Zarka advises, cosmopolitanism must be refounded in the age of globalization on solid, yet not introspective, philosophical bases. In this context, I find Pierre Bourdieu’s formulation particularly apt: we also need intellectual universalism.

“There are cosmopolitan people, cities, and societies, but for me, true cosmopolitanism must be intellectual and literary”

How would you define an “intellectual” in today’s world?

It is not a favourable time for the figure of the Intellectual, yet we need it more than ever. Since the eighteenth century, the intellectual has been a person of letters who creates public space with their work. By the nineteenth century, due to the prestige achieved through their literary contributions, intellectuals intervened in the public space with moral authority, making themselves heard and read to denounce the falsehoods and dead ends that society itself constructs. They set the truth in motion, as Zola famously put it. This is critical thinking, which should characterize the intellectual. They must speak uncomfortable truths, using their only weapon — the word — to mobilize their fellow citizens. However, this should not be done in a pamphleteering or dogmatic manner, as some have done, but through intelligent and thought-provoking texts. Their writings should be thinking machines, designed to make people think.

“The figure of the writer no longer holds the public weight it had a century ago”

In these times when it seems that anything goes, even if it serves no purpose, we need intellectuals more than ever. Yet, the figure of the writer no longer holds the public weight it had a century ago. Nevertheless, we need the intellectual attitude to prevent the dissolution of society into nothingness. One way to achieve this is to reread Josep Pla and Joan Fuster. Pla, in a self-interview published in Revista de Catalunya in 1927, wrote: “Every intellectual, when everything has been talked about, is always by definition a creator of freedom. And well, freedom is created by being free”. Fuster develops this idea in his Diaries in 1956: “(…) freedom. The man of letters today has never stopped thinking about it. (…) Only if his freedom is guaranteed — both internal and external — does the man of letters believe he can continue being a man of letters. (…) The man of letters today neither feels nor wants to be a stranger to the vital issues of his world. On them, he has a vision. In them, he participates and influences as much as he is allowed. And in reality, he does not conceive his literature disconnected from the conclusions he has reached in this regard. Literature and — forgive the inadequacy of the lexicon — opinion are a single and indistinguishable entity in his calculations. The freedom he is so jealous of is radically necessary for him: without freedom, there is no possibility for him to take responsibility for the problems, nor is there the possibility of literature”. Perhaps we are not sufficiently aware that in the face of the rise of fascism in Europe and in our country, even if there are no great intellectual figures, we should all collectively adopt their attitude. As Victor Klemperer asked the Germans just after the fall of Nazism, we must restore intelligence; “we must become a people of intellectuals”. Given the current state of affairs, we must write in legitimate defence.

Tell us about your passion for Stefan Zweig.

It is directly related to my discovery of the Café. Once I began reading European literature with this perspective, Stefan Zweig emerged as a key figure for me. First, I read his memoirs, where this phrase seemed to anachronistically define my ideal of life:

The best academy to inform ourselves of all the novelties was the Café. To understand this, one must recognize that the Viennese café is a very special institution, unparalleled by any other similar establishment in the world. In fact, it functions as a kind of democratic club open to anyone seeking a cup of coffee at a reasonable price, where any customer, for this small contribution, can sit for hours conversing, writing, playing cards, receiving mail, and above all, consuming an unlimited quantity of newspapers and magazines. In a high-quality Viennese café, all Vienna newspapers were available to the public, as well as those of the German Empire, France, England, Italy, and the United States, in addition to all the important literary and artistic magazines in the world. Nothing has contributed so much to Austria’s intellectual ease and international orientation as the fact that in the Café one could be informed of all the events in the world and at the same time discuss them with friends.

“Reading all of Zweig can reveal to us the complexity of Europe and help us understand his suicide as a European in exile”

In 2005, I published my first brief essay on literature and Cafés in the magazine L’Espill, titled “El solatge de la modernitat,” but the research was not yet mature enough. I continued reading, searching, and delving deeper. I kept reading and rereading the novels that had made him a classic, along with biographies, essays, and short stories. I discovered El llibreter Mendel, a 1929 story that fascinated me even more than the memoirs, and I read it as the negative of the image presented in El món d’ahir. Two years later, I published Poética del Café, which included a 100-page chapter on Zweig. In those pages, I already hinted at a certain suspicion that readings by Karl Kraus, Robert Musil, Edward Timms, and Claudio Magris among others had led me to. This drove me to deepen my research, seeking French translations of his essays, Diaries and correspondence, which had mysteriously not been published in our country despite the publishing boom and reader success. I promoted the translation into Catalan of the articles he published in the Viennese press in the early moments of the Great War at Edicions de la Ela Geminada, which contradicted the serene and pacifist version of the memoirs. I also promoted the publication in Catalan of Petita Crònica, which includes El llibreter Mendel. With all this translated, I was able to write the Catalan version of those 100 pages, completed with new findings, resulting in Stefan Zweig. Els suïcidis d’Europa. Curiously, my publications on Stefan Zweig may seem very severe regarding his figure, but in reality, they are written from the deepest admiration for a great European writer whose entire body of work we must read, not just limit ourselves to the perfect but sugary novels. Reading all of Zweig can reveal to us the complexity of Europe and help us understand his suicide as a European in exile. If we simplify our reading of hm, his death, and his work will have served no purpose.

Thirty years have passed since you won the Guerau de Liost poetry prize with your book Els vianants (1995). What was that poet Antoni Martí like? Why this sustained interest in cities and their landscapes?

In the 90s, I aspired to be a poet. Initially, writing in Spanish during school, and later at university under the influence of Foix and the classes of Jaume Pérez Montaner. I was surrounded by great poets: Pérez Montaner himself, Isabel Robles, Ramon Guillem, Xúlio Ricardo Trigo, Ramon Ramon, Joan Elies Adell, and the whole group of La Forest d’Arana: Begonya Mezquita, Manel Rodríguez Castelló, and many others who have continued to write verses. Perhaps I wanted to be a poet, but poetry did not want to be in me, except in the poetic textures of my diaries or essays, as Ramon Guillem observed with irony and insight during the act of presenting L’home impacient in Valencia. I think, in retrospect, that the same thing happened to me as to Joan Fuster, probably due to his influence. I transitioned from poetry to diaries and essays, and sorry for the redundancy. From that book, I would only save the title which, as you mentioned, reflects a concern for the way of walking through the city, already influenced by the readings of Charles Baudelaire and Walter Benjamin. That is what remains of that young and handsome poet. Now I am still handsome… and a prose writer.

How do you see the future of Comparative Literature Theory? Do you think robots will devour us?

Literary Theory introduced a transformative approach to text analysis. It was necessary to overcome biographical and positivist literary history to focus solely on the text. This shift meant not seeking to uncover the author’s hidden intentions or the documentary evidence of the era and environment in which they lived—practices still prevalent in contemporary philology. Instead, the approach advocated for engaging with the text in a dynamic way, constructing meaning anew with each reading and rereading. Comparative literature plays a crucial role in this process due to its openness to an infinite array of interpretations that transcend political, linguistic, and disciplinary boundaries. Comparatism extends beyond simply drawing parallels between works in different languages. It involves linking literature to history, law, philosophy and more, offering a broader and more complex perspective on literature. In fact, great comparatists have always been writers inspired by Goethe’s concept of Weltliteratur, an idea celebrating its bicentenary in 2027, and which is still the background of values and ideals of comparative literature today: a contribution of literature for a more peaceful future.

“Computers, despite having a vast repository of words, lack the genuine intelligence. That is, the natural, word-based (logos) thinking that intricately relates words with an inherent sensitivity unattainable by algorithms”

Yet, such depth of analysis cannot be replicated by artificial intelligence. Computers, despite having a vast repository of words, lack the genuine intelligence. That is, the natural, word-based (logos) thinking that intricately relates words with an inherent sensitivity unattainable by algorithms. Experiments on poetry and combinatorics have been done, but a computer will never reach infinity through the combustion of the dictionary. In contrast, we find infinity in a single verse by Paul Valéry and freedom in one by Paul Éluard. This way of writing-reading is insurmountable. Similarly, the misguided notion of replacing books with laptops in schools has been criticized as a detrimental move that could leave long-lasting negative impacts if not reconsidered.

Is L’erosió (2021) a novel? A travel chronicle? A reflection on time? And how do you see Argentina today?

L’erosió is the work I cherish most among my creations. However, as your question implies, it did not have an easy journey. Between 1996 and 1998, I habitually carried a notebook and pen, chronicling my daily life, and in August of those years I travelled to Argentina to teach. Upon transcribing these entries, the sections set in Argentina exhibited a distinct intensity, compelling me to develop them further. Consequently, upon returning from Buenos Aires, I ceased writing diaries.

The book was initially published in 2001 as part of a new collection by Edicions 62 titled No Ficció, a decision driven by editorial reasoning I never fully comprehended. As J. V. Foix wrote: “Do fictions, and I do live by fictions, enslave the mind or are they its celestial paths?” I remain uncertain about where L’erosió should be categorised: Essay? Travel literature? Novel? Diaries? Memoirs? The Anglo-Saxon label of Non-Fiction, uncritically adopted here, has always struck me as narrow and reductive, devised by editors solely focused on market niches. Categorising books into niches seems, to me, to stifle their essence.

Autofiction? I am unsure. It slightly irks me that despite the current fascination with this genre, no one mentions L’erosió as a potential precursor to this literary phenomenon at the turn of the century. The book features numerous annotations that, while implausible, did occur in my life, alongside invented memories—events that never happened to me but unfold in the book. During its creation, I would visit the Rambla every Sunday to purchase La Nación and Clarín, the two principal Argentinian newspapers, to evoke involuntary memories through reading.

L’erosió was an unconventional book in 2001, receiving an equally unconventional reception: some reluctant reviews—including two contrasting ones in the same newspaper—alongside enthusiastic praise from Jordi Sebastià in El Temps, a scathing critique in the Quadern of El País, where an article also appeared with calculated but kind coldness, and a very accurate one by the late Valencian essayist Josep Iborra. It must be said that the book’s resonance was primarily due to the interest and generosity of various literary critics, as the publisher made little effort to promote it or the collection, which vanished as suddenly as it had appeared. This was unfortunate, as other noteworthy books were published in the collection, such as Maria Barbal’s Camins de quietud, Valentí Puig’s Cent dies del Mil·leni, a reissue of Montserrat Roig’s indispensable Els catalans als Camps Nazis, Toni Sala’s Petita Crònica d’un Professor de Secundària, Fatema Mernissi’s L’harem occidental, and several historical or political titles. After five years, the entire collection was terminated. The sleepless nights of writers, the relentless efforts of translators, the remembrance of extermination camps, the landscape of La Franja, and my walks in Buenos Aires (and Rosario, omitted from the cover) were all consigned to oblivion, becoming another chapter in the turbulent history of Catalan literature.

L’erosió was an unconventional book in 2001, receiving an equally unconventional reception: some reluctant reviews—including two contrasting ones in the same newspaper—alongside enthusiastic praise from Jordi Sebastià in El Temps, a scathing critique in the Quadern of El País, where an article also appeared with calculated but kind coldness, and a very accurate one by the late Valencian essayist Josep Iborra. It must be said that the book’s resonance was primarily due to the interest and generosity of various literary critics, as the publisher made little effort to promote it or the collection, which vanished as suddenly as it had appeared. This was unfortunate, as other noteworthy books were published in the collection, such as Maria Barbal’s Camins de quietud, Valentí Puig’s Cent dies del Mil·leni, a reissue of Montserrat Roig’s indispensable Els catalans als Camps Nazis, Toni Sala’s Petita Crònica d’un Professor de Secundària, Fatema Mernissi’s L’harem occidental, and several historical or political titles. After five years, the entire collection was terminated. The sleepless nights of writers, the relentless efforts of translators, the remembrance of extermination camps, the landscape of La Franja, and my walks in Buenos Aires (and Rosario, omitted from the cover) were all consigned to oblivion, becoming another chapter in the turbulent history of Catalan literature.

Perhaps it should simply be read as a book. I believe that in 2001, it was quite an unusual book, emerging without context. The works of W. G. Sebald had just been published in Barcelona and he was still merely a cult author for the initiated. Moreover, it appears that a prestigious publisher rejected it on the advice of a stubborn professor.

Around 2018, Ramon Ramon intervened providentially. My friend, who had read the first edition of L’erosió, wrote me an email that lifted me from my lethargy, made of printer ink and bound sheets. The subject line read: “L’erosió is beautiful and solid”; and the content of that email resembled more a moral epistle than a routine electronic message. Ramon is not only a great poet but also one of the finest diarists in Catalan literature, and one of the most profound readers of that book at the time. Alongside his comments on the ideas of escape, solitude, and literature, he insisted on two fundamental points: that the book absolutely needed to be translated into Spanish—or Argentinian Spanish—so that Argentinians could appreciate the beautiful and profound work that was, ultimately, dedicated to them; and that efforts should be made to reintroduce L’Erosió to Catalan readers. Inspired, within a few weeks I completed the Spanish translation, which I had begun during my spare time, making use of the hours gifted to me daily by Renfe’s delays.

I read that email just before embarking on another escape, this time to Canfranc—an abandoned border station in the heart of the Pyrenees in Huesca that I visit twice a year if I can, once in summer and once in winter, mainly to observe the progress of the works aimed at restoring international railway traffic, with the impatience of one day being able to take a direct train to Tolosa de Llenguadoc. Filled with enthusiasm, immediately after reading my friend’s words, I wrote an email to Minúscula, an editorial I deeply admire. Admittedly, I did so like one casting a bottle into the sea, using the generic contact address listed on their website. The content of my email was a brief and timid greeting, with an attached document: La erosión. A few days later, when I was already at that shipwrecked transatlantic in the mountains, I received a response directly from the editor Valeria Bergalli. She expressed not only interest in publishing it but also in creating a new edition of the original version. My shouts of joy could be heard from Teruel. The next day, I began walking north, spending a few days in Tolosa, but this was not another escape. Upon taking the train back, I felt for the first time in a long while, eager to return to Girona to review both versions. When I met with Valeria Bergalli, everything seemed ironically connected: the editorial’s headquarters is located precisely on Avenida República Argentina, and we can add that she herself is Italo-German-Argentinian. That is to say, a great European reader who became one of the best editors in the country with a publishing house that started in 1999, just when I was drafting the final version of a book— “twenty years is nothing”—which is now in her catalogue. Another circle closed.

Twenty years later, when it appears in Minúscula, everything was different. The context had integrated Sebald as a turning point in European literature, Claudio Magris had consolidated his Europeanist Catalan audience, Latin American authors such as Ricardo Piglia and Sergio Pitol—who had already made their mark in Argentina—were being reissued in Barcelona and championed by Enrique Vila-Matas, who had finally found the success that had eluded him in the 1980s with Bartleby y compañía. Even Macedonio Fernández was beginning to be mentioned.

“Regarding today’s Argentina, it continues a bit as always. It is a wonderful country with a fascinating capital — a great European city misplaced on the continent?”

Today, L’erosió is back in bookstores accompanied by La erosión, with the cover I always dreamed of: a perspective of Avenida Santa Fe in Buenos Aires, where I often walked on my way to the Kavanagh building, visible on the horizon, and the Estación de Retiro photographed by Horacio Coppola. I haven’t changed anything despite predictable temptations. But since someone might doubt this statement, I can point out an annotation that, conceived in 1998, remained unwritten and I reconsidered in the Spanish translation in an unequivocally Pla’s gesture. It is a brief reflection on sinister stains on the Buenos Aires map discovered shortly before going to the Airport. This correction of a geographic error and some amended errata are the only variants to be found.

However, many things have changed in my spirit regarding this book. Seeing it again in bookstores, the reactions on Twitter, for example, the interviews conducted by some very intelligent journalists and good writers and of course, the pleasant gathering on the day of the presentation, come to make up for the past trials when L’erosió was seeking an impossible editor two decades ago.

Regarding today’s Argentina, it continues a bit as always. It is a wonderful country with a fascinating capital — a great European city misplaced on the continent? — but which makes its life impossible every two decades. Peronism, dictatorships, Menem… now with Milei, it is a bit of everything but with throes of ridicule.

What are you up to or thinking about right now?

Right now, I am responding to a very intelligent interview. But if you ask about books about to be published, I have three. One on Walter Benjamin, Marcel Proust, and Ramón Gómez de la Serna, which won the latest Walter Benjamin international award; another on railway reflections about Canfranc and Portbou, two places I often visit especially to think about Europe and myself. And also, a collection of my essays from the 90s to 2021, most of which appeared in Revista L’Espill, where I grew up as an essayist. It will be titled L’Estació del Nord and will have on the cover an image of this very important station in my life, a detail that makes me very excited.

Can you recommend us some current Catalan narrative?

In narrative, in the broadest sense of the word, not only limited to the classic novel, I believe we are at a very important moment. Firstly, our good fortune lies in being contemporaries of Josep Palàcios. The reading of his books, edited and rewritten continuously over the last half-century, is a genuine monument. Gathered in La Imatge, I would highlight separately the three versions of AlfaBet and El Laberint i les nostres ombres en el mur.

“Joan Benesiu’s novels represent two European works of remarkable dimension that will continue to provoke thought for decades. Similarly, Francesc Serés’s books “

Joan Benesiu’s novels represent two European works of remarkable dimension that will continue to provoke thought for decades. Similarly, Francesc Serés’s books, especially La pell de la Frontera and the trilogy De fems i de marbres, possess enduring qualities. Allow me to advocate for revisiting two works by Salvador Company: Els relats de Lawn Tennis, which includes one of the finest stories from the post-war period, and Silenci de Plom, a narrative artifact that stands among the most complex and intriguing creations by Catalan writers at the turn of the century. In diaries, those by Feliu Formosa will be absolutely enduring. He has paved a path followed, for example, by Ramon Ramon, who is the best writer of diaries and poet of what we might call my generation, if such a thing exists.

Do you have a favourite philologist? Who would you regard as a master?

While I don’t have a favourite one, Erich Auerbach stands out as the most significant German Romance philologist—and comparatist—of the twentieth century. His work, including Mimesis, has profoundly influenced my critical perspective. Additionally, his concise essays, such as Philology of Weltliteratur (1952), serve as manifestos for the future of Comparative Literature. One key phrase from Auerbach’s writing resonates: “If humanity wishes to emerge unscathed from the shocks induced by such powerful concentration processes, so vertiginously rapid, and so internally ill-prepared, we will have to get used to the idea that in a uniformly organized Earth, only one literary culture will remain alive or, even in a relatively short time, only a few literary languages will remain, soon perhaps only one. And if so, the idea of Weltliteratur would be realised and destroyed at the same time”. I consider these words as a categorical imperative for Comparative Literature.

Among contemporary Catalans, I had the immense fortune of having Jaume Pérez Montaner as a professor of contemporary Catalan literature and a master of poetry. I still keep the editions of Nabí by Josep Carner and Elegies de Bierville by Carles Riba with the highlights I made in his classes, which continued later over a coffee.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons