- Humanities

- 7 de October de 2024

- No Comment

- 8 minutes read

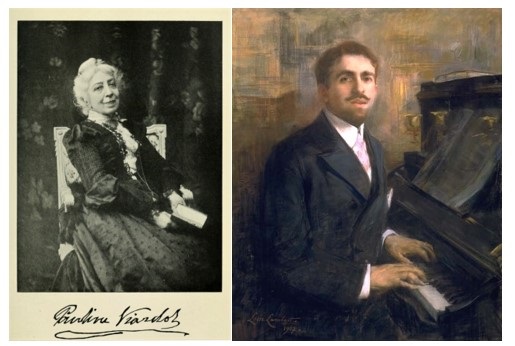

A conversation chez madame Viardot-García in Paris

A conversation chez madame Viardot-García in Paris

. / Wikicommons

In 1933, the Venezuelan musician Reynaldo Hahn de Echenagucia (1874–1947) published Journal d’un musicien, a text filled with fascinating anecdotes from his youth, referencing various artistic figures of the Belle Époque, just before the outbreak of the First World War, in which he served as an infantry soldier. A lyrical singer, composer, pianist, and theatre producer, Hahn had studied at the Paris Conservatory alongside Ravel, Viñes, and Cortot. His friendships with Diaghilev and, especially, with Proust, granted him a privileged view of the twilight of the 19th century and, later, the interwar period.

In 1901, Hahn visited the renowned Madame Viardot-García at her third-floor flat on Boulevard Saint-Germain, where she had moved in 1883 after the deaths of her two husbands, Louis Viardot and Ivan Turgenev, just months apart.

First, the great artist would recall her trip to Granada in the summer of 1842, almost sixty years earlier, where she sang Il barbiere di Siviglia, the opera Rossini had composed for her father, and for the first time in her career, Bellini’s Norma, a role her sister, Maria Malibran, had performed magnificently.

Visit to Mme Viardot. Large, dimly lit salon, old-fashioned, opulent, but nothing surprising; a good fire; on a chair in front of the piano, a shawl left there by the elderly artist. She enters, slightly hunched, very amiable. Her famous ugliness is softened by age. She has beautiful white hair, simple, thick. Her eyes are slightly outlined with kohl; she still has all her teeth, which must have once been dazzling and, though yellowed now, retain their brilliance. A large, very cheerful mouth, voice of a robust old woman, low, resonant. She is eighty years old, but everything about her, except her eyes, which can barely see, is full of life, of fire. She coughs a lot, with a cold, and when I ask if she is taking care of herself, she replies with serious yet comic importance: ‘Oh, I have too many things on my bedside table!’ We talk, one thing after another: ‘I’ve been told you’re Spanish!’ And voilà, she begins speaking in a captivating Andalusian accent with an extraordinary agility and purity. ‘Hey!’ she says, ‘Am I not Spanish? Have I not spoken Spanish my whole life? With my father, my sisters, my daughters?’ Moreover, Madame Viardot had always had a reputation as a polyglot; she speaks all languages, understands Russian… She told me that in Granada, where she had sung Norma, the enthusiastic audience had demanded Spanish songs after the performance, and she and one of her colleagues had to have a piano brought onto the stage to sing, dressed in Druidic attire, vitos and peteneras!1

And after a few questions about repertoire, focusing on the works of the time…

I tried to steer the conversation towards certain points that interested me. I asked her why she didn’t write her memoirs. She said it was because her vision was too poor to write for long periods and she didn’t know how to dictate. This led us to talk about her eyes, as she had cataracts. I mentioned surgery… ‘These horrible glasses, these coke bottle glasses I’m forced to wear!’ A rather unexpected coquetry, I thought, in an eighty-year-old woman who had always been considered unattractive. Suddenly, she asked me: ‘Do you like the cheesy way in which people sing? Is it necessary to have this exaggerated diction?’ I tried to seize the opportunity to talk about diction. But I couldn’t. She kindly but firmly said, ‘Will you sing something for me?’ I sat at the piano, an old, tired instrument where I didn’t feel quite comfortable; a chair too high, and who knows what else. But it didn’t matter; my listener knew enough to prevent me from fearing the worst due to a vocal accident. I sang Néère, which seemed to please her, then Le cimetière, which she requested. Her white head with thoughtful eyes nodded approvingly at times. ‘I like how you sing’, she said calmly, as though granting a gesture of satisfaction: ‘It’s simple, that’s good’.

…The conversation would turn to Mozart’s Don Giovanni, which Pauline Viardot-García had performed for the first time in New York alongside her family, with a small role added by her father, in the presence of Lorenzo Da Ponte himself, Mozart’s librettist, admired such a premiere in America, which was performed for the first time in Prague, in old Europe, in 1787.

‘Madame, did you enjoy singing Don Juan?’

‘Yes, I sang both Anna and Zerlina. I enjoyed Anna very much’.

She nodded constantly, seeking the right words and finding them, precise and brief.

‘Have you read Hoffmann?’

‘Certainly,’ I replied. ‘He suggests that Donna Anna may have been loved by Don Juan…’

‘That’s right! I sang that role in that spirit. I sought to express that nuance’.

‘But it seems very difficult to me, as Anna barely exchanges words with Don Juan, leaving little opportunity to convey any amorous inflection’.

And I asked if she mixed grief with hatred to emphasize that aspect.

‘Yes. And it can also be indicated in the moment when she recognizes him as her nocturnal aggressor’.

‘And perhaps also in her slight indifference towards Don Ottavio?’

‘Oh, indeed! Poor Ottavio! He’s a bit of a fool. I remember the famous tenor Bordogni, singing with me after the story of my struggle with Don Juan, exclaimed “respiro!” [sic in Italian] which made the audience laugh’.

I told her that this word had always seemed ridiculous to me and, recently, in Germany, how dangerous that effect could be in a modern theatre.

‘How do they say this in German?’

‘Ach! Ich athme wieder!’ [Oh! I breathe again!]

She repeated the phrase with a perfect accent, accompanied by a subtle gesture.

In short, she did not believe that Hoffmann’s hidden thought had ever crossed Mozart’s mind, but she felt it could be used to enhance the role’s interest.

Madame Viardot-Viardot had purchased the original manuscript of Don Giovanni, written in Mozart’s own hand, in London in 1855. The manuscript had travelled from Paris to Baden, London, and finally back to Paris, where it resided in her Saint-Germain apartment for the admiration of visitors—though Reynaldo Hahn was never able to see it. This remarkable relic was donated to the Conservatoire de Paris in 1892, and today can be accessed digitally via Gallica, a division of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, bearing the name of its former owner on the title page:

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b55002493z/f4.item.r=don%20giovanni%20pauline%20viardot

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons