- History

- 29 de January de 2026

- No Comment

- 10 minutes read

Enough Is enough: the first feminist demonstration in Barcelona (1910)

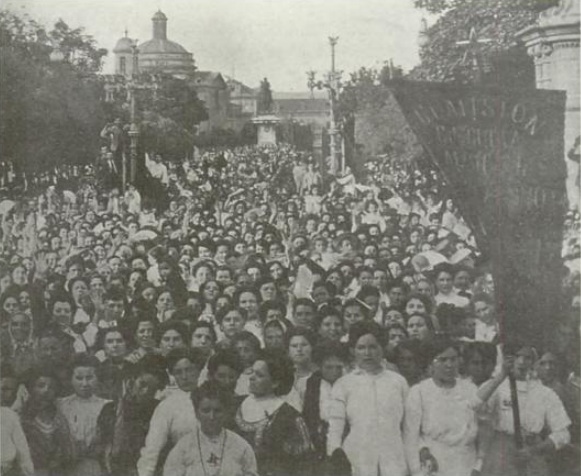

Coloured photograph of the women’s demonstration in Barcelona, 10 July 1910 / Source: https://barcelodona.blogspot.com/

Soledad Bengoechea

Mujeres, dejad de ser hembras, diamantes enlodados, flores repletas de detritus nocivos, sol tras plomizos nubarrones, para convertiros en seres pensantes y conscientes, en deslumbradora pedrería, en flores frescas y doríferas, en sol espléndido y vivificador

Women, cease to be mere females—mud-besmirched diamonds, flowers choked with noxious debris, a sun veiled by leaden clouds—and become instead thinking, conscious beings: dazzling gems, fresh and gold-bearing flowers, a radiant, life-giving sun.

(Author’s translation; no official English version exists.)

Ángeles López de Ayala, El Gladiador de Librepensamiento, 1917.

On a day of oppressive summer heat—10 July 1910—Barcelona became the stage for the first major women’s demonstration in the history of both Catalonia and Spain. The immediate trigger was a protest against the claim by certain religious women’s associations to speak on behalf of all Spanish women in matters such as education. More significantly still, this marked the first occasion on which women publicly demanded political rights.

A singular woman: Ángeles López de Ayala

Although it arrived comparatively late when measured against more industrialised countries, feminism in Catalonia produced, from the mid-nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth, a number of prominent figures—some of them born elsewhere in Spain. From a social standpoint, Catalan feminism was plural from its very beginnings. It developed along a broad spectrum ranging from the intellectual bourgeoisie—figures such as Dolors Monserdà, Francesca Bonnemaison and Carme Karr—to working-class republicanism and anarchism, represented by activists such as Ángeles López de Ayala and Teresa Claramunt.

Born in Seville in 1858, López de Ayala arrived in Catalonia shortly after turning thirty and became the most influential promoter of a particular strand of feminism that laid the groundwork for developments that would fully emerge in the 1930s. This early freethinking feminism was distinguished by its working-class orientation, secularism, anticlericalism and republicanism. With these features, it broke free from the narrow reformist confines of bourgeois feminism and extended its reach to the popular classes.

Through the pages of numerous newspapers and magazines, López de Ayala consistently argued for the necessity of women’s emancipation. Women, she insisted, had to liberate themselves from the constraints imposed by the Church and religion. She contributed to newspapers such as El Clamor Zaragozano, La Publicidad and El Diluvio, as well as to magazines including La luz del porvenir, after meeting its renowned editor—also a writer and spiritualist—Amalia Domingo Soler. Blind from birth, Domingo was involved in several Masonic lodges that practised spiritualism, among them El Gran Oriente Espiritista, founded in 1891. That same year, together with López de Ayala and Teresa Claramunt, she helped establish the first feminist nucleus in the Spanish state: the Sociedad Autónoma de Mujeres (Autonomous Women’s Society), later replaced by the Sociedad Progresiva Femenina (Progressive Women’s Society) in 1898.

López de Ayala also founded and directed a succession of periodicals: the weekly El Progreso (1896), republican in outlook and frequently concerned with women’s conditions and social problems; El Gladiador (1906), likewise freethinking and feminist, which succeeded El Progreso; El Libertador (1910); and finally, El Gladiador del Librepensamiento (1914). This last publication disappeared in 1920, together with the Sociedad Progresiva Femenina, of which it served as the official organ.

Precedents: the Sociedad Autónoma de Mujeres of Barcelona (1892) and the Sociedad Progresiva Femenina (1897)

The idea of women’s equality with men—an inheritance from the French Revolution and the Enlightenment—emerged in Catalonia in close association with freethinkers and republicans. The groundwork laid by earlier feminists gradually consolidated, giving rise to new initiatives. Journalistic activity continued, but a decisive shift occurred: women came to realise that the printed word alone was insufficient to secure the changes they sought, and they resolved to take their demands into the streets. These were women who had received a cultural education markedly different from the norm. At the same time, the first working-class female leaders began to appear: factory workers and mothers capable of sparking unrest or of mobilising once it had begun, organising or joining strikes and riots. Such actions were usually prompted by shortages or price rises in essential goods—such as the coal and bread riots of January 1918—although other motivations also played a role, as in the case of the women who demonstrated during the Tragic Week of 1909 to prevent their male relatives from being sent to Morocco.

As the historian Felip Belmonte has noted, “one of the most prominent institutions in the defence of women’s role in society at the beginning of the century was the Sociedad Autónoma de Mujeres of Barcelona. It was the first feminist association in Spain and was founded by López de Ayala, together with Amalia Domingo Soler and the Sabadell-born anarcho-syndicalist Teresa Claramunt, in 1892, although references to it can already be found in 1889”. The society was initially based on the now-vanished Carrer de la Cadena—located in what is today the Rambla del Raval—before moving to Carrer Ferlandina, 20. Its activities focused on organising women-only events devoted to political debate as well as cultural and educational topics. It also financed an evening school for adults, the Fomento de la Instrucción Libre de Barcelona, located at Carrer Sant Pau, 31. Both institutions were closely linked to the Constancia Masonic Lodge.

At the end of 1897, the Sociedad Autónoma de Mujeres was transformed into the Sociedad Progresiva Femenina. Initially regarded as the most important feminist association in Spain—despite its activities being confined to Catalonia—it was led by López de Ayala and served as a meeting place for women associated with the Constancia Masonic Lodge. Based in the Gràcia district, it was first housed at Carrer Sèneca, 2, until 1900, when it moved to Carrer Torrijos, 7, remaining active there until 1920. The association denounced the double oppression and exploitation suffered by women: both as women and as members of the working class. In response, it called for a republican society founded on liberty, equality and fraternity.

The first feminist demonstration (1910)

The first feminist demonstration in Barcelona took place in 1910 and was organised jointly by the Agrupación de Damas Rojas, the Asociación de Damas Radicales and the Sociedad Progresiva Femenina. Although López de Ayala was the principal driving force, the march was formally led by an executive committee composed of one representative from each organising body: Laura Mateo, Francisca Gimeno and Ángeles López de Ayala respectively. The demonstration enjoyed the backing of Lerroux’s Radical Party, as evidenced by the participation of the Damas Radicales on the organising committee.

According to contemporary accounts, López de Ayala marched at the very heart of the procession. The event constituted the first genuine feminist demonstration ever held in Spain. Approximately 20,000 women from Barcelona and surrounding areas took part, in what some sections of the press described as a display of “anticlerical, liberal and radical women”. The demonstration remained peaceful throughout. La Vanguardia, which covered the march, reported that among the participants was a young girl “dressed as the Republic”, while many demonstrators carried caricatures depicting the Republic kicking a friar. Women walked arm in arm through the streets, under a blazing sun, wearing the long, ankle-length skirts typical of the period, chanting slogans and singing songs as they went.

The demonstration concluded in front of the Civil Government building, where the organisers submitted a petition bearing 22,000 women’s signatures demanding limits on the power of the Catholic Church.

Thus ended an event whose purpose was to make clear that women were not subject to the authority of the Catholic Church and that they were capable of thinking for themselves. It is worth recalling that the belief that “the confessor dictates the vote” was one of the arguments deployed against women’s suffrage—an argument that Clara Campoamor herself was forced to confront repeatedly in the 1930s, before the Second Republic finally recognised women’s right to vote.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons