- Psychology

- 8 de January de 2026

- No Comment

- 8 minutes read

Learning situations and conditions according to Gagné

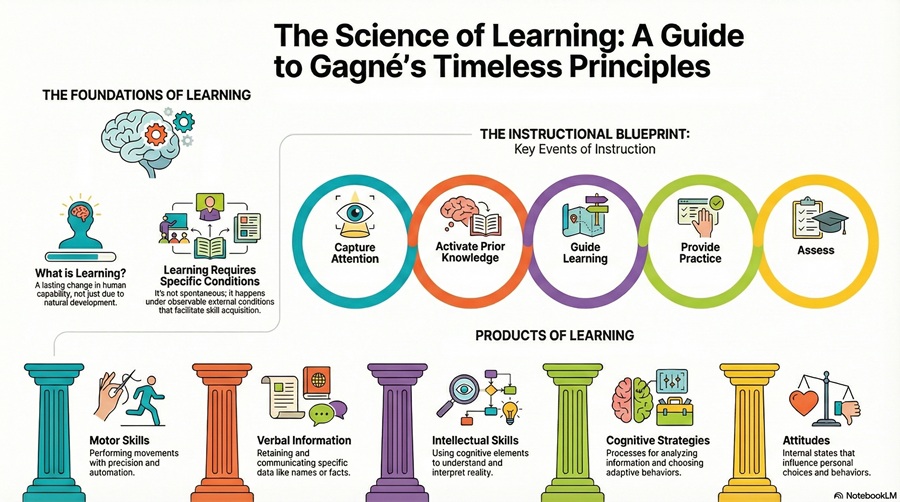

Infographic summary generated by NotebookLM for this article.

Robert Mills Gagné (1916–2002), though little known to many teachers, is one of the central figures of twentieth-century educational psychology and instructional design. He developed a systematic theory of how learning takes place and under what conditions the process occurs. His major work, The Conditions of Learning (1965), is a rigorous attempt to define learning from a scientific perspective by identifying the elements that make it possible and the factors that limit its effectiveness in educational settings. One might add that it ought to be compulsory reading for every teacher.

Gagné (1965) defines learning as a relatively permanent change in human disposition or capability that cannot be attributed simply to development. This change manifests itself as an observable modification in behaviour, inferred from a comparison between an individual’s performance before and after exposure to a learning situation. This self-evident point implies that assessing and considering students’ prior knowledge before teaching and instructional action is essential. Learning may be reflected in an increased capacity to carry out a given activity, or in changes to attitudes, interests, or values. It is a change that must persist for a minimum period of time and that must be assessable through recall (Ruiz, 2020). It is therefore clearly distinguished from changes that arise from mere maturation or natural biological development.

For Gagné, learning is not a spontaneous event but a process that takes place under observable conditions. In this sense, Gagné (1965) defines a learning situation as the set of external conditions that facilitate the acquisition of a new capability. As these conditions are observable and describable, they allow us to establish relationships between what the environment affords and the changes that occur in the individual. This opens the door to the development of scientific theories of learning, since the process ceases to be opaque and becomes analysable and replicable. Unfortunately, much research is still not conducted under such conditions.

Despite the model’s explanatory scope, Gagné is clear about the limits of learning effects: not every dimension of education can be addressed solely through the principles of learning. He specifies that aspects such as motivation, persuasion, or the formation of attitudes and values—highly relevant to education—do not respond directly to the same conditions that explain the acquisition of skills and knowledge. Thus, learning is a necessary but insufficient element for encompassing the full complexity of human development.

From this perspective derives a precise conception of how learning should be planned and directed. To plan is to identify the capabilities to be developed and determine which external conditions will support their acquisition. These must be ordered coherently and sequentially. To direct learning is to control and adjust educational events—activities, guidance, reinforcement, feedback, pacing—with the aim of activating the internal processes through which students acquire a new competence or body of knowledge, and through which they reflect upon and regulate their own learning. Today we would call this metacognition.

Gagné (1965) grouped the great variety of learnings into eight types: signal learning or reflexes; stimulus–response conditioning; chaining of motor sequences; verbal association; discrimination; concept learning and understanding; learning principles to structure one’s own judgements; and problem-solving. The products of learning include motor skills, verbal information, intellectual skills, cognitive strategies and the development of attitudes (Table I).

| Category of learning | Brief description |

| Motor skills | Motor skill and the automation of movement enabling precise action. |

| Verbal information | Capacity to convey and retain specific data such as names or memories. |

| Intellectual skills | Capacity to grasp, interpret and use cognitive elements to make sense of reality. |

| Cognitive strategies | Processes for acquiring, analysing and retrieving information and selecting adaptive behaviours. |

| Attitudes | Internal states that influence behavioural choice and are gradually modifiable through learning.

|

Table I: Learning Outcomes According to Gagné (1965).

Finally, Gagné (1965) also described teaching methods that foster learning, emphasising the importance of organising educational activity into explicit events: gaining attention, activating prior knowledge, guiding learning, providing practice and feedback, supporting transfer and promoting retention. He also highlights the need for a gradual, instruction-led approach based on learners’ initial level—an anticipation of what later came to be known as evidence-informed teaching (Ruiz, 2020)—and of frameworks such as UNESCO’s work on educational technology.

All these principles remain strikingly relevant in the age of artificial intelligence: far from being out-dated, they offer a framework for understanding how AI technologies can function as pedagogical tools. Technology must be rethought (Diéguez, 2024). If AI can adapt external conditions to stimulate internal learning processes—personalising guidance, offering tailored reinforcement, generating meaningful practice, helping learners recall and identify areas of need—it merely extends, in a digital environment, the scientific logic of Gagné’s model.

Even so, technology must always remain under the teacher’s supervision. It must be introduced at the appropriate moment so that it does not become a substitute tool that induces cognitive offloading and circumvents the learning process, but rather an instrument for improving the environment and the learning situation in Gagné’s sense. In this respect, his work continues to provide a solid foundation for designing effective learning experiences in today’s technologically mediated education—whether we like it or not.

References:

Diéguez, A. (2024). Pensar la tecnología. Barcelona: Shackleton Books.

Gagné, R.M. (1965). Las condiciones del aprendizaje. Madrid: Aguilar. Edition of 1971.

Hernández-Fernández, A. (2024). Inteligencia artificial para docentes según la UNESCO. Educational Evidence. https://educationalevidence.com/inteligencia-artificial-para-docentes-segun-la-unesco/

Ruiz, H. (2020). Com aprenem. Barcelona: Graó.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons