- Opinion

- 3 de December de 2025

- No Comment

- 8 minutes read

From Groundhog Day to The Exterminating Angel

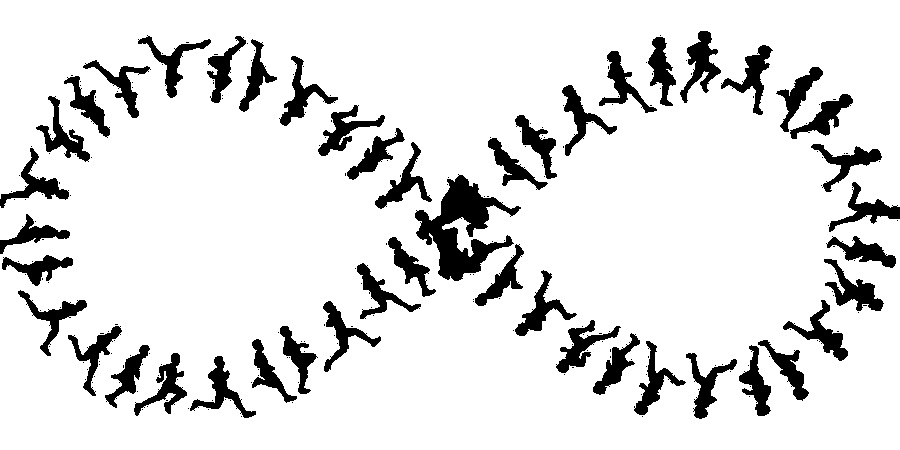

We are still facing the same educational problems as ever. Yet no one questions the model itself, nor whether we might go beyond it—only how to live within it, and perhaps even off it. / Gordon Johnson – Pixabay

A loop is a path endlessly retraced, a course that repeats itself indefinitely without any apparent break in continuity—like the spiral twist of a lock of hair. An eternal return of the same sequence of variations and events.

The best-known example, which has entered popular idiom, is Groundhog Day (Harold Ramis, 1993), that ingenious film starring Bill Murray and Andie MacDowell. A journalist sent to a remote American town to cover the Groundhog Day festival wakes up each morning to find that the date is the same as the day before. Once he grasps what is happening, he begins to act differently when faced with the same recurring situations—until, at last, he finds the “right” way of responding and time resumes its course. The day itself remains the same, but what happens within it changes—because his different reactions generate new chains of events.

What concerns us here, however, is a different kind of loop—one far more common in real life than any metaphor spun from a science fiction premise. In this case, time moves forward, yet what keeps repeating are the same situations, the same problems, and our inability to recognise or respond to them differently. If Groundhog Day presented a temporal loop, this is a conceptual one. The calendar does not freeze through an anomaly in space-time. No. Time flows on, like the river of Heraclitus—but we do not. We continue, again and again, to crash against the same headland looming ahead of us. With no break in continuity.

Like in The Exterminating Angel (1962)—for me, one of the greatest films ever made—in which Luis Buñuel presents a vision of collective mental paralysis: a state that prevents us from escaping the fiction we ourselves have created. A brilliant metaphor for what sociology calls the Thomas theorem: “if people define situations as real, they become real in their consequences”.

A group of upper-class guests attend a formal dinner in a lavish mansion after a night at the opera. Following the meal—already marked by odd incidents and a faintly oppressive atmosphere—come the obligatory after-dinner conversation and a short piano recital. It is late, yet no one makes a move to leave. To the hosts’ astonishment, the guests begin settling into armchairs and sofas as if to spend the night there. Some are gobsmacked, but none depart…

The next morning, outwardly keeping up appearances, the butler enters to serve breakfast. When he turns to leave, however, he freezes on the threshold—unable to cross it. The guests reproach him, yet none of them dares to cross either, and everyone tacitly accepts that, although nothing visible stands in the way, the doorway cannot be passed. And so, they remain, arranging themselves for a long stay in the drawing room, which soon begins to resemble a pigsty. Their only concern is how to endure their strange predicament—not why it exists— concerned only with how to get by in it and whether someone from outside might come to rescue them. They do not know that those outside are equally afraid to come in.

As reality decays, chaos follows: quarrels, thefts, hysteria, flirtations, attempted sexual assaults. A young couple commits suicide; a man dies of anguish; a woman succumbs for lack of medicine. The most “reasonable” among them merely urge the others to maintain decorum and cooperate for survival—yet none even hint at the obvious: that there is no physical obstacle, no visible threat preventing them from leaving. They share a curious consensus that the threshold cannot be crossed, but no one asks why.

Eventually, one of them recalls that on the first night, after the piano recital, a guest had asked the pianist to play one more piece. She had declined, saying it was late and she was tired, but eventually relented under the group’s insistent pleading. They now “realise” their “mistake”: in pressing her, they must have violated some rule of etiquette, disturbing the cosmic order and bringing upon themselves this paralysing fear. To lift the spell, they decide to recreate the exact circumstances that caused it—as if by some homeopathic ritual. Everyone resumes their former position; the pianist plays the same piece; when it’s over, everyone breaks into applause, just as they had before; the same man again requests an encore; she again refuses. They all agree it is late and time to go. And this time, they cross the threshold without incident.

Convinced that a miracle has occurred, they organise a Te Deum in thanksgiving. But when the mass ends, the priest and acolyte notice that no one leaves—and neither do they. The film closes with a flock of sheep entering the church from outside, to feed those trapped within.

In Groundhog Day, the protagonist eventually understands the nature of his anomalous reality and learns to change his responses to the identical situations confronting him each morning. Desperate trial and error, to be sure—but there was no other way, however uncertain, if he was to break out of the loop in which he was ensnared. He cannot fully comprehend the reality he inhabits, yet he learns to read it and act accordingly.

Not so the characters of The Exterminating Angel, trapped in an extreme version of the Thomas theorem. They accept as real a fiction of their own making, and it becomes true in its consequences. They decide they cannot leave—and so they do not. Failing to grasp the illusion of their construct, they fall back into it at the first opportunity. They have learned nothing and remain prisoners of their own fiction.

The situation Buñuel portrays is uncannily similar to our current condition in education. We continue to face the same old problems, yet the model itself goes unchallenged. No one asks whether it might be possible to go beyond it— only how to live within it, and perhaps even off it. The prevailing educational model has become the only conceivable habitat. A failed system born of an imagined fiction that has turned real in its consequences, with all its very tangible dysfunctions.

Until we dare to step outside it, we shall remain paralysed—mentally trapped in the loop we have ourselves created. All it would take is to cross the threshold. But perhaps some fear too much what they might find beyond it—in reality—and therefore choose to remain inside their comfortable sty, their little enclosure, snug within the illusion.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons