- History

- 4 de November de 2025

- No Comment

- 9 minutes read

Ferrer y Guardia and la Escuela Moderna

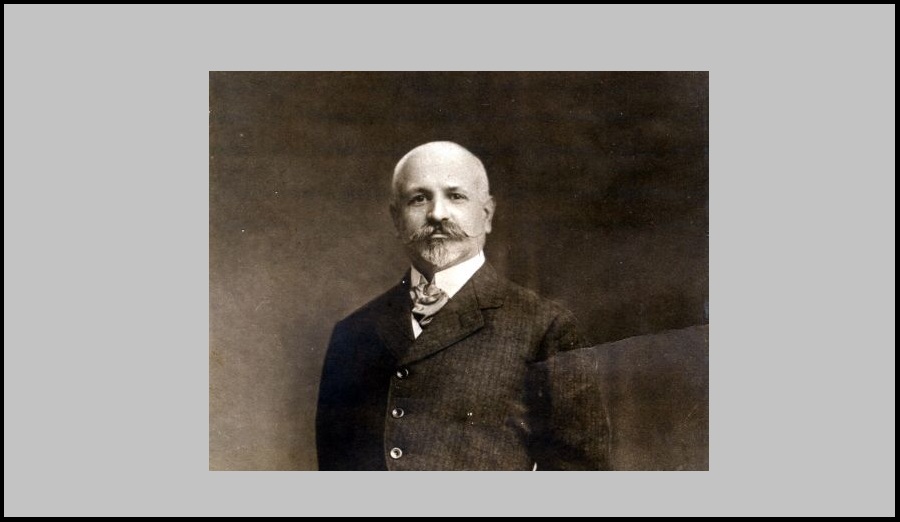

Francesc Ferrer y Guardia photographed circa 1909. / Wikimedia

Soledad Bengoechea

The figure of Francesc Ferrer i Guardia is not very well known among the general public, as the various campaigns launched against him damaged his reputation. By contrast, he enjoys considerable recognition in cultural and historical circles, and especially among education professionals interested in understanding who the promoter of the Escuela Moderna was—a school founded on the principle of providing secular, rational, and scientific instruction. Ferrer was an educator who saw education as a tool to change society, who believed in its transformative power, and who aimed to shape students into intellectual revolutionaries. Consequently, his legacy continues to be the subject of debate.

Some years ago, while consulting the archives of the Fomento del Trabajo Nacional (FTN), I began reviewing the organisation’s minutes from August 1909. I wanted to ascertain whether the employers’ association had commented on the events in Barcelona between 26 July and 2 August—later termed the Tragic Week—which would ultimately trigger Ferrer’s trial and execution. I was taken aback when, upon reaching the minutes of 4 August, I found a note in Catalan: “Fa remarcar el Senyor President [Lluis Muntadas Rovira] el caràcter anàrquic que prengué tot seguit el moviment i la vinguda del conegut agitador Ferrer-Guardia que el dilluns es deixà veure públicament a Barcelona” (The President [Lluis Muntadas Rovira] emphasised the anarchic character that the movement immediately assumed and the arrival of the well-known agitator Ferrer-Guardia, who on Monday made a public appearance in Barcelona). Elsewhere, in Madrid, in the Archivo de la Fundación Antonio Maura (AFAM), I came across a letter dated 10 August 1909, addressed to Prime Minister Antonio Maura from Muntadas, asserting that Ferrer: “was the instrument that propagated disorder in Barcelona when on Monday he appeared publicly in the city”.

In a rushed trial on 9 October 1909, Ferrer—accused of being the instigator and leader of the Barcelona uprising—was found guilty and sentenced to death. One cannot help but wonder to what extent Muntadas’ accusations— he was no minor figure, but a prominent Catalan textile industrialist and president of the FTN—shaped the outcome. The sentence was carried out in the ditches of Montjuïc Castle, Barcelona shortly afterwards, on the morning of 13 October.

The news sparked protests across Europe, particularly in Paris. Ferrer was widely regarded as a martyr of free thought, sacrificed by Catholic intolerance for promoting an educational model that sought to liberate children from religious dogma.

Let us now turn to his life.

Francesc Ferrer i Guardia was born on 10 June 1859 in Alella, near Barcelona, to moderately affluent and devoutly Catholic farmers. It was here that he would be arrested on 31 August 1909. By the age of thirteen, he had left school and begun working in Barcelona. He quickly rejected the orthodox values instilled by family and school, and by adulthood, Ferrer had become a republican and free thinker.

At twenty, he joined the Madrid, Zaragoza and Alicante Railway Company. In 1886, he supported the military uprising led by General Villacampa, a follower of republican Ruiz Zorrilla, aimed at proclaiming a republic. After its failure, Ferrer went into exile in Paris with his partner, Teresa Sanmartí, with whom he had three children. He earned a living teaching Spanish and working as an unpaid secretary to Ruiz Zorrilla. Deeply interested in anarchism, he participated in the 1892 Universal Congress of Free Thought in Madrid, organised by the International Federation of Free Thought (Brussels). Ferrer was also known for his vigorous anticlerical advocacy, having joined the Masonic Lodge Verdad of Barcelona in 1883.

Separated and later remarried, Ferrer spent the first ten years in Paris in poverty and agitation. He never denied his links to the Spanish Progressive Republican Party, attending its assemblies regularly. Nor did he ever admit to being an “anarchist of action”, an instigator of attacks. By this time, Ferrer was already convinced that no political revolution could succeed in Spain while a large portion of the population remained illiterate, and another large portion was educated under the prevailing values of the time.

From 1901, he began publishing the weekly La Huelga General. That same year, a childless French friend, Ernestina Meunier, bequeathed him a substantial fortune. This allowed him, in September, to found what would become the renowned Escuela Moderna at 56 Bailén Street, Barcelona. However, the school had a brief existence, open only from 1901 to 1906, during which it was censored several times. Yet the seed planted then left a lasting legacy. The Escuela Moderna’s founding charter reads: “It was an educational institution aimed at radically transforming pedagogical experience in a critical, secular, rationalist, and libertarian sense. According to Ferrer i Guardia, it was a school in which boys and girls were to enjoy ‘unusual freedom, engage in exercises, games and outdoor recreation, maintain harmony with the natural environment, practice personal and social hygiene, and from which exams, prizes and punishments would disappear’”.

The novelty of the Escuela Moderna lay, first, in the application of more or less modern and scientific pedagogical methods, and second, in instruction based on a clearly rationalist, humanitarian, anti-militarist, and anti-patriotic doctrine. Naturally, it provoked deep fear among clerical and conservative minds. Ferrer remained a fervent revolutionary until the end. As mentioned, he had concluded that Spain was not ready for political revolution, and his goal was to prepare future “revolutionaries” through education.

One initial difficulty Ferrer faced was finding teachers capable and willing to put his educational ideas into practice.

Here it is worth asking: was Ferrer an anarchist? He consistently opposed capitalist and military domination and exploitation, though there is no evidence he promoted idealistic visions of social organisation. In any case, he was an idealist, a supporter of liberty and equality. There is also no proof that he was ever a terrorist. Perhaps in the early 1890s he might have been willing to support an uprising, but from 1892 onwards, he underwent a change. In a “Declaration of Faith” written while awaiting trial—for alleged involvement in the attempted assassination of the Spanish king by Mateo Morral—published in 1906 in España Nueva, he stated his detestation for all political parties, whether anarchist or Carlist, and argued that any party was an obstacle to the educational mission of the Escuela Moderna. He added: “I have always denied to the court that I was an anarchist”, and concluded:

“And if I am labelled an anarchist on the basis of a published statement in which I discuss ideas of mental demolition, I must respond that here are the books and Bulletins of the Escuela Moderna, in which one will indeed find ideas of demolition. But note well: ideas of mental demolition, that is, the introduction into the mind of a rational and scientific spirit that will dismantle all prejudice. Is this anarchism? If so, I confess I was unaware of it; but in that case, I would be an anarchist only insofar as anarchism embraces my concepts of dedication to peace and love, and not because I have adopted its methods or processes”.

In this sense, Ferrer is better described as a free-thinker and freemason than strictly as an anarchist. Nevertheless, after his tragic death and subsequent elevation as a European symbol, virtually the entire contemporary anarchist movement claimed him as their own.

The night before his execution, he wrote a will in which he stated: “I wish that on no occasion, near or distant, for any reason, there be religious or political demonstrations at my remains, because the time spent on the dead would be better devoted to improving the condition in which the living exist, which almost all men greatly need. (…) I also wish that my friends speak little or nothing of me, for men become idols when exalted, which is a great evil for the future of humanity. Only deeds, whoever they belong to, should be studied, praised, or condemned—praised if they seem to contribute to the common good, or criticised if they are deemed harmful to general welfare”.

At the moment of his execution, Ferrer faced the firing squad calmly, composedly, and with a clear voice, shouting: “I am innocent! Long live the Escuela Moderna!”

Ferrer is said to be considered “the most famous Catalan in Belgium”, and about sixty streets bear his name in France, Belgium, Portugal, and Brazil. Paradoxically, history has elevated him to the status of an idol, despite his insistence that he never wished to be one. In Barcelona, in 1990, a monument to Ferrer was inaugurated on Avenida del Estadi: a bronze sculpture by Auguste Puttemans depicting a nude human figure atop a pedestal, raising a torch to the sky.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons