- Economy

- 15 de October de 2025

- No Comment

- 20 minutes read

Thrice a rebel: education as a driver of economic progress and gender equality

Painting of the poem ‘Divisa’ by Maria Mercè Marçal, on the walls of the Institut Pere Calders in Cerdanyola del Vallès (Barcelona). / Photo: Aurora Trigo

“I thank chance for three gifts: to have been born a woman,

of the working class and an oppressed nation,

and the murky blue of being thrice rebellious”

(Adapted from Maria-Mercè Marçal, Catalan poet)

These verses by Maria-Mercè Marçal resonate powerfully in the lives of countless women who, to this day, face multiple layers of discrimination in the workplace. Being a woman, far from protecting us, often places us in a position of vulnerability within a system that continues to reproduce inequality. Fortunately, education remains, across all societies, the most effective mechanism for breaking cycles of poverty and exclusion. For women, it not only opens the door to better employment and higher incomes but also has the power to transform deeply rooted social structures. Even today, women systematically earn lower wages than men across the world, and rates of female poverty remain disproportionately high — particularly in contexts where access to education is limited (UN Women, 2023).

The hypothesis guiding this article is straightforward: investing in education means investing in equality, since the gender gap in wages and opportunities that affects women can be substantially reduced through access to high-quality education.

The importance of education in determining future income

Economic theory has repeatedly demonstrated that education is one of the most influential factors in determining individual income. Human capital theory, developed by economists such as Becker (1964) and Mincer (1974), holds that education enhances individual productivity, which in turn translates into higher wages throughout a person’s working life.

The concept of the “return to education” has become one of the most widely used indicators in the economics of education to quantify the individual benefits of investing in human capital. According to Psacharopoulos and Patrinos (2018), each additional year of schooling is associated, on average, with an 8% to 10% increase in future earnings. This finding, confirmed across multiple contexts and methodologies, highlights that education is not only a fundamental right but also one of the most profitable investments for both individuals and society as a whole. The same authors note that, on average, women continue to experience equal or even slightly higher private rates of return than men — that is, each additional year of schooling tends to lead to a similar or greater percentage increase in salary for women. Moreover, education generates numerous indirect effects: it reduces the likelihood of unemployment, strengthens cognitive and non-cognitive skills, and facilitates adaptation to a constantly changing labour market (OECD, 2021).

For women, these dynamics are even more decisive. In societies where wage discrimination persists, higher qualifications enable access to less feminised sectors with better pay (World Bank, 2018).

Yet, even though women obtain similar or greater returns from education, a substantial gender pay gap remains. The academic literature generally explains this persistent difference through three key factors:

- Occupational segregation and field of study choice: women tend to cluster in sectors and occupations that are less well remunerated. In other words, even with the same level of education, career paths strongly influence future income. Fields dominated by women are often devalued. It is not merely that these jobs are “paid less” by the market, but also that women are overrepresented in feminised fields of study and sectors — such as education, social work, or certain areas of healthcare — which tend to offer lower salaries. This limits the full realisation of educational returns (Seehuus & Strømme, 2025).

- Career interruptions and part-time employment: differences in labour market participation across the life course (for reasons such as maternity or family caregiving) reduce women’s lifetime earnings. Studies that examine long-term returns find that, in some cases, women experience higher benefits from education over their working lives, but career interruptions for family-related reasons often offset those gains (Tamborini & Sakamoto, 2015).

- Wage discrimination and corporate practices: even among individuals with similar educational levels and comparable occupations, gender wage gaps persist due to discriminatory remuneration, promotion, and negotiation practices. OECD reports (2022) document that, despite progress in education, gender pay disparities remain in many countries as a result of sex-based discrimination.

This evidence indicates that investing in education can narrow part of the wage gap by enabling women to increase their earnings proportionally more than men when accessing higher education. Although segregation by field of study and discrimination still exist, investment in educational policies can help women enter high-return sectors such as finance, technology, management, energy, or telecommunications. Achieving this requires not only raising overall educational attainment but also encouraging greater diversity in educational and career choices and tackling gender bias in academic and vocational guidance.

International Comparison: Female Poverty and Literacy Rates

The relationship between education and poverty is clearly reflected in international statistics. According to UNESCO (2023), there are still 773 million illiterate adults worldwide, two-thirds of whom are women. This educational disparity translates into profound economic inequalities: women account for 70% of the global population living in extreme poverty (UN Women, 2023).

In sub-Saharan Africa, girls are 2.5 times more likely than boys to be out of school (UNICEF, 2022). In South Asia, rates of child marriage remain strongly correlated with the lack of access to secondary education. Such deficits restrict women’s participation in the labour market and perpetuate the cycle of poverty (World Bank, 2018).

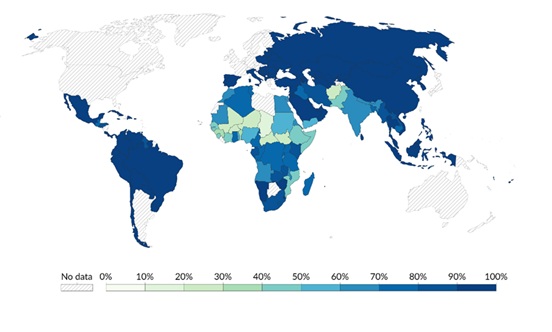

Percentage of women aged 15 and over who can read and write, 2023

Note: UNESCO literacy rates refer to the percentage of people aged 15 or older who report being able to read and write, with understanding, a short and simple statement about their daily life.

The map above shows the regions of the world with the lowest levels of female literacy, such as sub-Saharan Africa and parts of South Asia, which coincide with extremely high poverty levels — confirming the close connection between women’s education and economic development. However, countries that have invested in female education have made remarkable progress.

Beyond the basic link between literacy and poverty, education represents one of the most effective strategies for raising women’s incomes and reducing gender gaps in the labour market. South Korea, for instance, achieved sustained economic growth largely thanks to universal schooling — including that of women — which significantly increased their participation in higher education and in the workforce (OECD, 2021). Nevertheless, achieving equality in educational opportunities does not automatically guarantee equality in income. The persistence of educational and occupational segregation, combined with career interruptions and wage discrimination, helps explain why gender pay gaps endure even in contexts where women have attained higher levels of education than men (OECD, 2022).

Why Is Education Important for Women?

Investment in women’s education remains decisive in reducing poverty and advancing towards economic equity. Higher levels of schooling expand women’s opportunities to access formal employment, enhance their bargaining power both within the household and in the labour market, and generate positive externalities for society as a whole: greater productivity, improved child health, and sustained economic growth (World Bank, 2018). Consequently, closing the gender pay gap requires a dual strategy: on the one hand, ensuring equitable access for girls and women to all levels and fields of education; on the other, implementing labour and social policies that allow the returns on this educational investment to be effectively translated into income equality.

Investing in women’s education has a multiplier effect. It not only raises individual earnings but also improves family health, nutrition, and overall well-being. A literate mother is 50% more likely to have her children vaccinated, and infant mortality rates drop significantly when women have access to primary and secondary education (UNESCO, 2023). Moreover, education reduces women’s economic dependence on their partners, thereby strengthening their personal autonomy and decision-making power within both family and community settings (UN Women, 2023). From a macroeconomic perspective, the World Bank (2018) estimates that closing the global gender education gap could increase global GDP per capita by up to 20% in the long term.

Women’s education is also closely linked to political and social participation. Women with higher education are more likely to hold leadership positions, contributing to institutional transformation and the promotion of more inclusive societies (OECD, 2021). Furthermore, educated women participate more frequently in the formal labour market and occupy higher-productivity jobs, contributing not only to their personal income but also to a broader tax base and more sustainable economic growth (OECD, 2022). From a social perspective, education strengthens civic capital: women with higher educational attainment are more likely to engage in community organisations, take part in electoral processes, and demand accountability from public authorities, thereby reinforcing democratic governance.

In addition, numerous studies show that women’s access to education encourages greater investment in the schooling of their sons and daughters, creating a virtuous cycle of intergenerational social mobility. In rural contexts and low-income countries, the schooling of girls and adolescents is also associated with reductions in child marriage and early motherhood — factors that often irreversibly limit women’s life and career opportunities (UNICEF, 2022). Taken together, this evidence confirms that investing in women’s education is not merely a question of social justice, but a central strategy for human and economic development on a global scale.

The Situation in Spain: Female Poverty and Educational Attainment

Spain presents an educational and labour paradox that is characteristic of Mediterranean economies: women have significantly outperformed men in academic achievement, yet this advantage has not translated into equal conditions in the labour market or wage parity.

On the one hand, women’s educational attainment has increased remarkably in recent decades. In 2024, 57% of university graduates were women. Moreover, the female early school leaving rate (15.2%) was lower than that of men (18.5%) (INE, 2024). This high level of human capital places Spain above the EU average in female educational achievement.

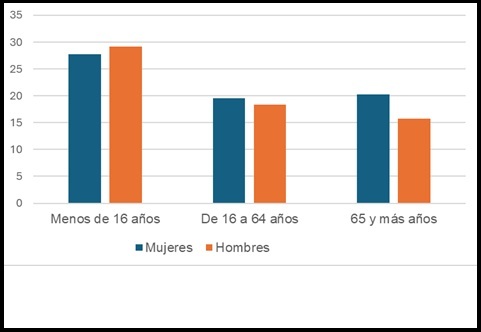

However, this qualification stands in stark contrast to the reality of the labour market. The gender pay gap persists: on average, women earn between 18% and 20% less than men (INE, 2023). In addition, in Spain, the risk of poverty is higher among women over the age of 16, as illustrated in Figure 2.

As Figure 1 shows, the risk of poverty and social exclusion is higher among women in almost all age groups, particularly from the age of 16 onwards. This vulnerability is further exacerbated among certain groups:

- Single-parent households: 82% of single-parent households are headed by women. This group faces a poverty risk rate of 49% (European Anti-Poverty Network – EAPN-ES, 2024).

- Older women: A study entitled Analysis of the Gender Gap in Pensions by the Women’s Institute (2025) reports that, as of January 2025, the average monthly pension for men was €1,564.53, while for women it was €1,071.76 — a gap of 31%.

- Long-term unemployment: In Spain, women account for around 56% of those experiencing long-term unemployment, revealing greater difficulties in re-entering the labour market (Fundación Adecco, 2025).

The causes of this gender gap can be explained by the same factors outlined in Section 2: Spanish women are concentrated in lower-paid and more feminised economic sectors and professions — such as education, healthcare, care work, and administration. In addition, the so-called glass ceiling continues to hinder women’s advancement: despite their high level of education, Spanish women remain underrepresented in senior management positions. Only 12% of board seats in IBEX 35 companies are occupied by women. In the public administration, while women make up 55% of all civil servants, their presence in top management roles does not exceed 40% (Grant Thornton, 2025). Another marked asymmetry in Spain lies in the distribution of domestic and caregiving responsibilities. Women devote, on average, two more hours per day than men to unpaid work (INE, 2023b). This imbalance forces many to opt for part-time employment: one in four employed women works part-time, compared with one in ten men. Many of these reduced working hours are involuntary and lead to lower earnings and reduced pension contributions in the future.

The Case of Catalonia: A Mirror of National Inequalities

Catalonia, as the autonomous community with the second-highest GDP in Spain, acts as a mirror that both reflects and, in some respects, amplifies the gender inequalities present across the country. Data from Idescat (2024) and the Barcelona City Council (2024) confirm that the gender pay gap in the region stands at around €6,500 per year — slightly above the national average. This disparity becomes more pronounced in age brackets where family responsibilities fall disproportionately on women, revealing how traditional gender roles continue to shape women’s professional and economic trajectories.

The feminisation of poverty is particularly well documented in the Catalan context. The rate of risk of poverty or social exclusion (AROPE) in Catalonia was 24.0% in 2024. When disaggregated by sex, women show a slightly higher rate (24.6%) compared with men (23.3%) (Idescat, 2024). However, these regional figures conceal harsher urban realities: according to the Barcelona City Council (2024), the female poverty risk rate in the city reaches approximately 40.5%, compared with 29% for men — an alarming figure that underscores the intensification of vulnerability in metropolitan areas.

This vulnerability is particularly acute among single-parent households, 80% of which are headed by women (Barcelona City Council, 2024). These households face not only greater economic hardship but also a heavy burden of unpaid work, which limits their ability to secure full-time employment or pursue professional advancement.

As in the rest of Spain, Catalonia continues to underutilise female human capital. Although the region records overqualification rates slightly below the national average (around 15–16%), a significant number of women graduates occupy jobs below their qualification level. This mismatch not only represents a loss of talent but also undermines regional productivity and constrains the innovative potential of the Catalan economy.

Occupational segregation is also clearly visible: Catalan women are concentrated in sectors such as education, healthcare, and social services — all of which, despite their high social value, remain systematically undervalued economically. By contrast, women’s presence remains limited in fields such as technology, engineering, and executive management, where remuneration is significantly higher.

In conclusion, the case of Catalonia demonstrates that women’s educational progress is a necessary but insufficient condition for achieving economic equality. What is required is a comprehensive approach combining educational policies with far-reaching labour reforms, gender-sensitive fiscal measures, a robust and publicly funded care system, and the eradication of cultural biases that perpetuate occupational segregation and the glass ceiling. Only through such measures can women’s human capital be fully translated into genuine equality of opportunity and outcome.

Conclusions: Recommendations for Economic and Educational Policy

The evidence is unequivocal: education is the most effective instrument for reducing female poverty and closing the gender income gap. However, its full potential can only be realised if it is accompanied by coherent economic and social policies.

Some key policy recommendations include:

- Universalise access to secondary and higher education for women, particularly in developing countries.

- Promote active labour market policies with a gender perspective, encouraging women’s entry into high-paying sectors and STEM careers (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics).

- Strengthen work–family reconciliation measures, ensuring public care services that enable women to participate in the labour market on equal terms.

- Address the gender pay gap through pay audits and sanctioning mechanisms for companies that engage in discriminatory practices.

- Promote female role models in education and research to inspire young women to pursue all professional fields.

In conclusion, education is not merely a fundamental human right — it is the lever capable of transforming women’s economic and social reality worldwide. Reducing the gender gap necessarily requires ensuring equal educational opportunities.

Maria-Mercè Marçal reminded us that to be born a woman, of the working class, and in an oppressed nation is to be “three times rebellious”. That rebellion is not only individual but also historical and collective. And it is precisely here that education acquires its full transformative power: it is the instrument that enables us to break social determinisms and open horizons of real equality.

As Nelson Mandela once said, “Education is the most powerful weapon you can use to change the world”. Ensuring that women also have access to that weapon is not an act of benevolence, but an essential condition for the economic, social, and democratic progress of any country.

References:

- Ayuntamiento de Barcelona. (2024). El género en cifras: condiciones de vida de las mujeres en Barcelona. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona.

- Banco Mundial. (2018). Women, Business and the Law 2018. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Becker, G. (1964). Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Fundación Adecco (2025). El número de desempleados de larga duración alcanza su valor mínimo en 15 años, pero castiga especialmente a las mujeres y a los mayores de 50 años. https://fundacionadecco.org/notas-de-prensa/el-numero-de-desempleados-de-larga-duracion-alcanza-su-valor-minimo-en-15-anos-pero-castiga-especialmente-a-las-mujeres-y-a-los-mayores-de-50-anos/

- Grand Thorton (2025). Informe Women in Business 2025. https://www.grantthornton.es/perspectivas/women-in-business/2025/

- INE. (2023). Encuesta de Estructura Salarial 2022. Instituto Nacional de Estadística.

- INE (2023b). Encuesta de Empleo del Tiempo (EET). Instituto Nacional de Estadística.

- INE. (2024). Estadísticas de educación y formación. Instituto Nacional de Estadística.

- INE (2025). Encuesta de condiciones de vida. Instituto Nacional de Estadística.

- Instituto de las Mujeres. (2025). Análisis de la brecha de género en las pensiones. Ministerio de Igualdad. www.inmujeres.gob.es/areasTematicas/AreaEstudiosInvestigacion/docs/Estudios/analisis_brecha_genero_pensiones_246p.pdf

- Mincer, J. (1974). Schooling, Experience and Earnings. New York: Columbia University Press.

- OCDE (2021). Education at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OCDE (2022). Same skills, different pay. Tackling gender inequalities at firm level. OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/gender/same-skills-different-pay-2022.pdf

- ONU Mujeres. (2023). Progress of the World’s Women 2023. Nueva York: ONU Mujeres.

- Psacharopoulos, G., & Patrinos, H. A. (2018). Returns to investment in education: a decennial review of the global literature. Education Economics, 26(5), 445-458.

- Red Europea de Lucha contra la Pobreza y la Exclusión Social (EAPN-ES). (2024). El Estado de la Pobreza en España. Informe AROPE 2024: pobreza ciclo vital. EAPN-ES. https://www.eapn.es/estadodepobreza/ARCHIVO/documentos/Informe_AROPE_2024_completo.pdf

- Seehuus, S., & Strømme, T. B. (2025). Gendered Returns to Education: The Association between Educational Attainment, Gender Composition in Field of Study and Income. Sociology, 59(3), 503-523.

- Tamborini CR, Kim C, Sakamoto A (2015). Education and Lifetime Earnings in the United States. Demography. Aug;52(4):1383-407

- UNESCO. (2023). Global Education Monitoring Report 2023. París: UNESCO.

- UNICEF. (2022). The State of the World’s Children 2022. Nueva York: UNICEF.

- World Bank (2025). World Development Indicators. World Bank. Acceso el 02-09-2025 en https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ADT.LITR.FE.ZS

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons