- Literature

- 6 de October de 2025

- No Comment

- 18 minutes read

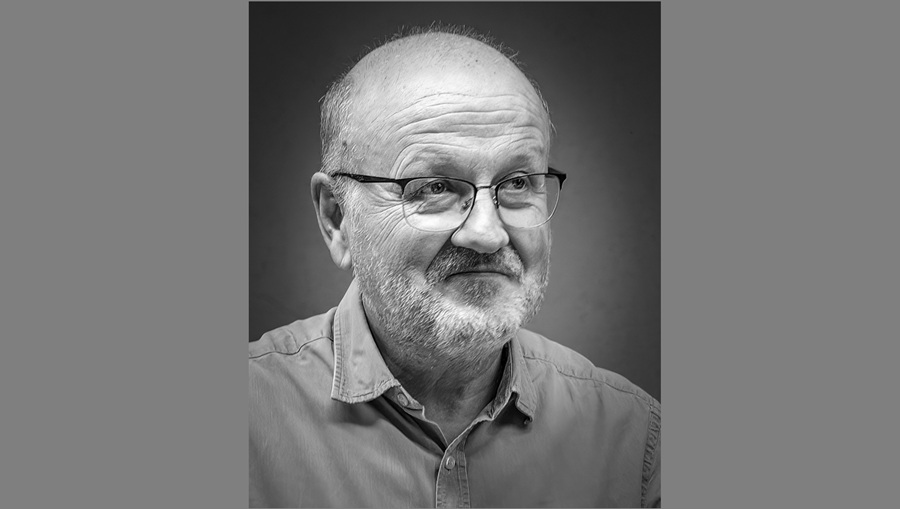

José A. Jiménez Navarro: “All poetry springs from a will to endure”

Interview with José A. Jiménez Navarro, poet

Aldarán, a publishing house primarily devoted to poetry, has just released Vísperas by José A. Jiménez Navarro (Cuenca, 1960). It is his second book—varied, polymetric, restrained. We spoke with this author, who builds his texts with unusual patience.

Claudio Rodríguez, Màrius Sampere, Blas de Otero—explicit presences in your pages…

Well… they are contemporary classics. Each of them possesses what Claudio would call “the gift of drunkenness”—that intoxicating power of verbal matter. And their writing, despite the very different poetics they practised, is clear and precise. I will confess to you that the title of the third part of Vísperas, “Luz en vilo” (literally, “Suspended Light”), came to me in the belief that it was my own creation, fitting the sense of latent, simmering life and the prominence of light in that section of the book. Only later did I realise it echoed Blas de Otero. I searched, and indeed found the line in his poem “La tierra”, from Ancia—an extraordinary book. It is not the first time this has happened to me: much of what we read we make our own, we internalise, and it remains with us for years until, on occasion, it resurfaces as though it were ours.

“Much of what we read we make our own, we internalise, and it remains with us for years until, on occasion, it resurfaces as though it were ours”

What surprises me most about Blas de Otero today is that even his poetry we might call “social” has stood the test of time, retaining its original freshness—something that cannot be said of most post-war “social” poets. I saw Claudio Rodríguez two or three times. On the first occasion, I was an absolute stranger to him—or perhaps because of that—he placed his hand on my shoulder and walked with me down a long corridor, confiding in me an amusing personal anecdote. He was a warm man. His poetry, the flow of his words, though by no means popular verse, still seems to me like laundry hung out in the sun, as he himself says in one poem, stirred by the winds of the Castilian plain, the Meseta.

As for Màrius Sampere, of the three you mentioned, he is the only poet with whom I have some personal familiarity. We once organised an exhibition of his paintings—an interest he soon abandoned—at the Espai Betúlia in Badalona, where I worked for many years. We saw one another often then. He is one of the Catalan poets who interest me most, among so many, and such fine ones. The news of his death reached me while I was in Morocco, among the dunes, visiting what they call “the gate of the desert”, in Merzouga. A poem in Catalan came to me spontaneously there—the one included in the book.

“I see María Zambrano in a car / overtaking a weary man”. Does that mean what I think it does?

I’ve no idea what you think it means—but probably, yes. The poem comes from a story told by Carmen Revilla, Professor of Philosophy at the University of Barcelona, after a lecture she gave on María Zambrano at the Espai Betúlia, which I just mentioned. On her way into exile in France, Zambrano, travelling by car with others, overtook Antonio Machado, who was on foot. On seeing the poet she so greatly admired—an ethical model of Republican Spain—and as the car was full, she chose to get out and continue on foot with him. The following verses of the poem refer to the “generation of sacrifice” or the “generation of the bull”, as Zambrano herself described her fellow exiles: on the one hand, sacrificed, expelled, erased by war; and on the other, given the circumstances, often deliberately renouncing their own fulfilment to fight for the Republic as their highest ideal.

How did the poem dedicated to Laura Luelmo come about?

The case of Laura Luelmo, as you know, had an extraordinary impact throughout Spain. Many of us were shaken by that vile crime against a young teacher, newly appointed to a village in the province of Huelva. I remember the demonstrations, where people carried banners that read: “We are all Laura Luelmo”. It was not a bad slogan of solidarity, but to me it felt facile, exculpatory. The hard part was acknowledging the passive complicity with machismo and the empire of brute force when not harnessed to any useful end.

“The hard part was acknowledging the passive complicity with machismo and the empire of brute force when not harnessed to any useful end”

I wrote a very harsh poem on this idea, changing the slogan of the demonstrations to “we are the murderer”, as part of a necessary and profound reflection pointing to a change in social attitudes. But it was too political, too explicit, and as I dislike sermonising, I left it aside. What remains is a more personal homage, starting from the magic of her name—its extraordinary sonority (Laura Luelmo)—leading us to the example of her life, centred on teaching and art, and cut so savagely short by violence. The reflection I leave to the reader who feels the need to pursue it. Perhaps the note at the end of the book, which explains the case, is enough to prompt such reflection. I don’t know if I was mistaken in revising the poem.

How would you define your poetics?

I cannot say with precision. First and foremost: to write well. That is, that the reader finds pleasure in the poem simply because it is well written. Later, other kinds of engagement may come—and it is to be hoped they do—but that initial pleasure seems essential to me. I like language to be clean, sober, precise, well-adjusted, shedding light on substantial matters, never yielding to abstraction, always close to specific human beings—in my case, often humble ones. Montale said that poetry must sing of what binds one person to others, without denying what makes each unique and unrepeatable. That is what I try to do.

On the other hand, I think all poetry begins with a will to endure; in that sense, it is always a celebration. If we want something to endure—and that is always the case when we write a poem—it is because we wish to celebrate what it reveals. For oblivion, no words are needed. There is something of a personal cemetery in Vísperas, and it is certainly more melancholy than I would wish, but also the epic of life—not least the sober, self-sacrificing lives of the men and women of my childhood, who never received the slightest recognition for what they did, yet held fast to their faith in personal effort and the solidarity of the community. I have always admired that. Now, in Vísperas, as in my earlier book Salvando las distancias, I wanted to sing and celebrate their effort and their trust in life: to bear witness to their existence. That, I think, could be a starting point to counter the opportunism, selfishness, and exhibitionism that rule the present world.

“There is something of a personal cemetery in Vísperas, and it is certainly more melancholy than I would wish, but also the epic of life”

On the other hand, I would also like to clarify, regarding the adjective “polymetric” you used in your entry in reference to Vísperas, that at the outset—both through my studies and also out of personal inclination—I immersed myself in classical Spanish poetry, so that the rhymes and metres that appear in my poems are spontaneous, rarely deliberate. With the exception of two poems— “Rondalla”, which is written expressly in octosyllabic quatrains, like the songs traditionally sung in Castilian villages, and “A una parra podada en abril” (literally, To a Vine Pruned in April), which is a sonnet because the first lines of the poem led me there—I have never deliberately sought rhyme or metre in this book.

I am well aware that nowadays few, if any, write in rhyme and even fewer in metre. Nor do I adhere to them regularly or follow established models. Yet rhymes—and more often certain metres—surface in my poetry as my creative freedom dictates, unbidden, for what matters to me above all is rhythm, the musicality of the verse, which in many cases sustains the composition. Beyond musical coherence, I believe rhyme fosters valuable associations and interweavings that lend the poems greater semantic depth. For me, undoubtedly owing to this grounding in classical poetry that I carry within, they arise spontaneously, just as an eleven-syllable or an eight-syllable line presents itself unbidden—not in speech, of course, but when I am writing poetry.

“Modernity in itself holds no appeal for me”

Writing is never entirely free, yet for me, having to suppress the rhymes that arise in my poems would constitute a form of musical and semantic self-censorship that I am unwilling to practise. In this sense, writing in freedom—even if it may seem otherwise—means allowing rhyme to surface whenever the composition calls for it, provided it contributes positively to the poem as a whole. Rhymes, particularly assonances, are a kind of caress that words offer one another. Why deny them such caresses? One need only consider the many traditional ballads to appreciate the natural ease with which the Castilian language embraces rhyme. Perhaps this gives the poems an archaic or traditional tone, but the aspect in itself does not seem important to me. What matters is the capacity to create or convey emotions and concerns bound up with the human condition, and that this message—if we wish to call it that—should offer the reader the pleasure of complicity, of vital recognition, and of aesthetic delight. Modernity in itself holds no appeal for me.

Since 1997 you have been part of the board of the Aula de Poesía in Barcelona…

The Aula de Poesia de Barcelona was founded by Jordi Virallonga, Eduard Sanahuja, Concha García and Federico Gallego Ripoll, with the support of the University of Barcelona, in 1991. The first two remained involved throughout. The Aula played a very important role in the dissemination of poetry in Barcelona during those years. I joined very soon as a member of its activities (I think I am member number 11) and later as a member of the executive board.

“The Aula played a very important role in the dissemination of poetry in Barcelona during those years”

Practically all the major poets of the Iberian Peninsula, in all its languages, and some Europeans, took part in its activities. The central cycle was the Jornades de Poesia i Mestissatge (literally, “Poetry and Crossbreeding Sessions”), which brought together, as I said, the most relevant figures of the moment. The role of connecting poets from different languages—and particularly between those writing in Catalan and in Spanish, who were not very familiar with one another—was crucial, as was the visibility given to poetry in our city. My main task was to coordinate the Aula de Poesía Prize in Barcelona, which admitted works written in Catalan, Spanish, Galician, Portuguese and, for one year, Italian, and which we hoped to extend to as many Romance languages as possible. It was a prestigious prize because we published the winning work in a bilingual edition, in a publishing house of each linguistic territory and, in Spanish, with Lumen.

Tell us about Caravansari, about its past and its present.

Although very similar to the Aula de Poesia project in its aim of building bridges between different languages and literatures, Caravansari was born—in 2005—as a project with a clearly Iberist vocation, as can be deduced from the subtitle of the journal Caravansari: revista de poesía en lenguas peninsulares (“Journal of Poetry in Peninsular Languages”). It also organised biennial sessions held in Santa Coloma de Gramenet, which brought together, following the same Iberist line, poets in the various peninsular languages, and which concluded, like the Jornades de Poesia i Mestissatge, with a joint recital of all invited poets.

It would be too lengthy to name all the people who have been part of the editorial board of Caravansari, but those who have sustained the project from the outset are Mateo Rello as director, José Antonio Arcediano, who was also involved in the Aula, and Edu Barbero, who took care of the graphic work until quite recently. I joined late, in 2014, when four issues of the journal had already been published and an extremely interesting series of publications of photography and poetry had been launched. Today only the journal survives in electronic format, which also provides the transcription of the sessions’ content.

Although the Aula de Poesia project was, in my view, more ambitious, especially because it had greater institutional backing, and also had two journals—one spoken, face-to-face, and another electronic—the Caravansari project has left behind, in addition to the electronic journal that remains alive, gradually incorporating new content, six highly interesting printed issues, one of which runs to almost 200 pages, and the photography and poetry publications I have mentioned.

Which authors are capturing your attention these days?

If you mean the authors who interest me in general, I would essentially say the same ones who have always captivated me, as they are inexhaustible: writers we regard as classics, and contemporary classics, particularly poets, in all the languages to which I have had access, mostly through translations—and they are far too many to enumerate here.

If you mean authors I am reading at present, I can name some of the books I have on my desk waiting to be read or finished: Devociones (Poesía reunida) by Mary Oliver; Os aviso que vivo por última vez (Anna Ajmátova y nosotros) by Paolo Nory; Hueso en astilla by Alfonso Alegre Heitzmann; Pensamiento y poesía by Hannah Arendt; No sufrir compañía (Escritos místicos sobre el silencio) by Ramón Andrés; Diez ventanas (Cómo los grandes poemas transforman el mundo) by Jane Hirshfield; Apocalipsi segons Marta (Antologia poètica) by Marta Petreu; Los recuerdos del porvenir by Elena Garro; El dolor de l’home i de les coses by Kostas Kariotakis; En espiral by X. L. Méndez Ferrín; El mes más cruel by Pilar Adón; Memorias: Mi medio siglo se confiesa a medias by César González Ruano; Com si fos una elegia by Coloma Lleal; Me he cruzado con un hombre que pasaba (Antología de poesía y prosa) by Joan Salvat-Papasseit; 51 Poemes by Gai Valeri Catul; etc. I think the oldest of those I have cited is Coloma Lleal’s, from 2001, and the most recent Paolo Nory’s, published in Spanish this very September.

“As Antonio Machado says, every social conquest of humanity comes accompanied, like the recoil of a shotgun, by a considerable and painful setback”

Would you describe yourself as ‘manriqueño’? Are things getting better or worse?

Literarily speaking, yes: Coplas a la muerte de su padre (Verses on the Death of His Father) seems to me one of the great poems of world literature. But I am not at all manriqueño in the sense of believing that “the good old days” were better; on the contrary, I think that almost any past era was worse: my parents’ life in the post-war period, though I celebrate it in my poems for the values I find in it, was much harder than ours; my grandparents’ life in the 1920s was at least as bad, if not more miserable still. Not to mention, to take a more distant example, how women were treated in the Middle Ages: they could be burned for witchcraft simply for declaring that they sometimes saw an aura around certain people. This led the inquisitors of the time to think they were in contact with the beyond, when in reality, as the neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks explains, it meant they suffered from classic migraine, i.e. with aura, with optical hallucination—such as I myself experience.

What happens is that, as Antonio Machado says, every social conquest of humanity comes accompanied, like the recoil of a shotgun, by a considerable and painful setback, and it seems that the world is now in the midst of a full-blown, bewildering regression.

When can we expect your next book?

I really don’t know; I am not a methodical writer. Since I do not believe the world needs my poems at all, I only write when I myself feel the need to say something, or to verbalise and, consequently, to order that which stirs within me persistently, disturbingly, obsessively. Then there will be no choice but to express it.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons