- Humanities

- 6 de June de 2025

- No Comment

- 10 minutes read

Pilar Bayona reflected in the mirror of her “selected correspondence”

Pilar Bayona reflected in the mirror of her “selected correspondence”

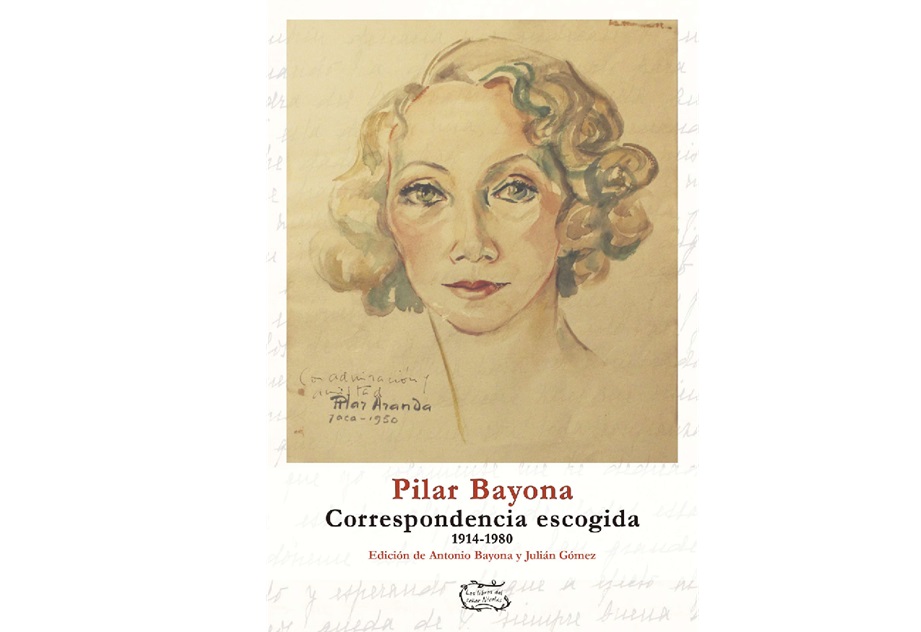

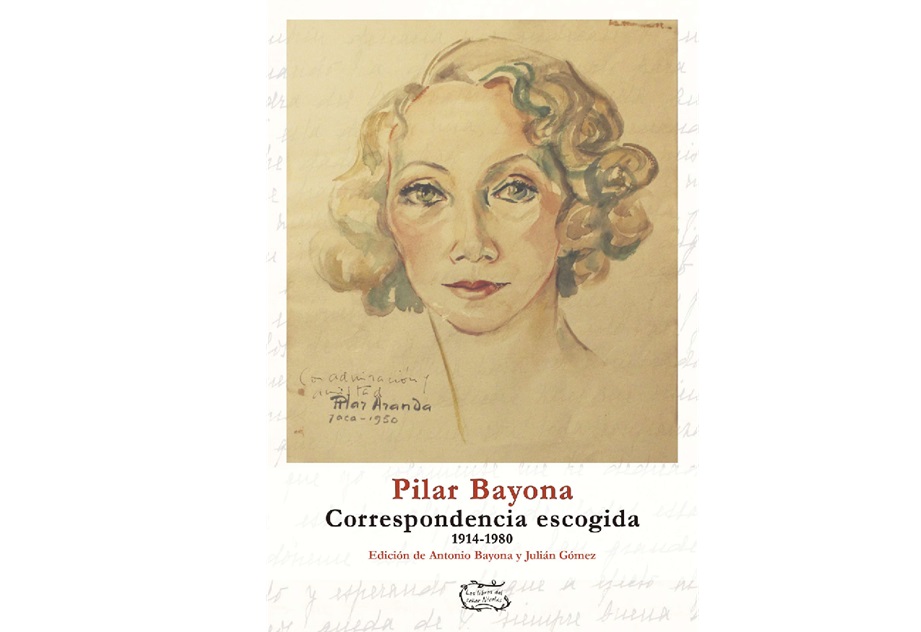

The recent publication of Correspondencia escogida de Pilar Bayona by Libros del Innombrable in collaboration with the Institución Fernando el Católico—part of the Diputación de Zaragoza—offers an invaluable glimpse into the life and artistic world of one of Spain’s most important musicians of the twentieth century. This edition, directed from the Pilar Bayona Archive by the pianist’s own nephews, Antonio Bayona and Julián Gómez, and introduced by the writer Juan Marqués, is particularly notable for the way it illuminates Bayona’s relationship with a constellation of figures who would shape the artistic landscape of the period.

Born in Zaragoza in 1897, Pilar Bayona was a child prodigy who soon found herself performing in both Barcelona and Madrid. She studied with the Sirvent brothers, themselves pupils of Joaquín Malats—the pianist who served as the muse for Albéniz’s Iberia suite. Bayona would go on to become a consummate interpreter of this monumental work. Albéniz had once written to Malats on 22 August 1907: “This work, this Iberia of my sins, I write essentially for you and because of you”.

Pilar Bayona performs Evocación, Lavapiés, Málaga, and Eritaña by Albéniz (1962)

Malats, in turn, had been a student of Juan Bautista Pujol, the pianist immortalised by Fortuny in his Fantasía sobre Fausto (1866), housed today in the Prado Museum.

Following the First World War, Bayona toured France and Germany with notable success. In a letter to composer Eduardo López Chávarri dated 10 October 1925—nearly a century ago—she described her impressions:

“I’ve met many musicians, and in Stuttgart, where I also performed, I was introduced to Maestro [Wilhelm] Kempf, director of the conservatoire, as well as to one of his female pupils who played in the modern manner: using her entire arm, straining tremendously and adopting the most dreadful posture—clearly exhausting, and most unnatural. The amusing thing is that what the Germans most appreciated was precisely my effortless style. They were enthralled by Falla and Albéniz, and by the other composers as well, although they found the works too slight—and to some extent, they’re right, for the Spanish repertoire lacks the kind of large-scale works they favour. They treated us extremely well and were, if anything, too generous”.

Pilar Bayona performs Toccata BWV 914 by Bach

Bayona maintained correspondence with many of the leading artists of her time: Buñuel, Falla, López Chávarri, Mompou, Joaquín Rodrigo, Todrá, Esplá, Remacha, Halffter, Samuel Rubio, Luis de Pablo, among others. A staunch advocate of contemporary music, she dedicated much of her energy to studying and premiering works for solo piano and chamber ensembles by composers of her generation.

Among the many artists in her circle, particular mention must be made of Carlos Baena, who would become principal cellist of the Spanish National Orchestra. Bayona and Baena shared a close, playful rapport, often exchanging clever wordplay and musical references. A particularly poignant example is the farewell formula frequently used in her correspondence, drawn from Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 81a, in which the composer bids farewell to the imperial family with the word Lebewohl—farewell—under the melancholic call of the horn evoked at the keyboard.

Beethoven, Sonata Op. 81a “Les adieux”.

“The day you left”, Baena wrote, “the four of us (your cousins, Galve and I) went for coffee (just to do something) at a café on Preciados Street, and we couldn’t bring ourselves to part ways. We felt a profound sadness. You were missing, your absence keenly felt, for you were absolutely essential. And yet the cruel reality was that you were departing—irrevocably—at a dreadful speed. Even had we wished to follow, our poor human forms could never have kept pace with that horrible machine carrying you away… I found myself living in a world of images, of memories glimpsed through the physical world around me—trams, underground, taxis, and so on. I spent several days thus, thinking of the True Music to which you had drawn me ever more deeply—that ineffable world of Debussy… until at last I succumbed to the weight of the strident reality in which I am now inescapably immersed” (December 1940).

There is a striking intimacy in the way other artists addressed Bayona, clearly speaking from a place of trust and deep affection. Luis Galve, another pianist from Zaragoza with a long and distinguished career, wrote:

“Dear Pilar: I’d love to hear just some of what you’ve said or thought about me—just some, because if I found out everything, I’d have to wring your neck. Anyway, here I am in letter form. We’ll see how long you take to reply, since you probably think that with that miserly postcard you sent, you’ve done your duty for the next five or six months” (Madrid, 13 February 1940).

“Dear Pilar: My left ear is burning from so much time on the telephone—talking to everyone to find you a concert. They all ended up directing me to the Philharmonic Orchestra, which indeed has it, and according to Carlos Baena (your tireless admirer… but what is it you give him, Pilarín?), Maestro Pérez Casas is more than happy to lend it to you. Carlos is handling the rest. Imagine—I even had the audacity to ask Cubiles himself, and he was extremely kind. He even said you were intelligent!” (Madrid, 2 April 1940).

“Dear Pilar: I’ve been meaning to write to show signs of life, but time slips away when one is working, and you see how it is… What sort of life are you living? Are you still practising? Aren’t you thinking of coming this way? You really ought to get out of Zaragoza for a bit—for many reasons. Otherwise, locked away down in that radio station basement, you’re going to end up like one of those charming mummies in the museums—or at best, looking like a tube station ticket clerk, which is more or less the same thing… Promise me you’ll never lose heart. Those who cannot play like you are the ones truly unfortunate. And don’t forget: injustice has always existed and will continue to exist for as long as the world turns. Don’t you dare leave me hanging. Send my regards to your brothers and friends out there—and a firm pinch for you, without letting Baena, Luis [García-Abrines], [Alfonso] Buñuel or [Juan Pérez] Páramo, or any of your endless entourage that surrounds you find out” (Madrid, 28 July 1940).

Pilar Bayona never married, and her life unfolded between Zaragoza and Pamplona, where she devoted herself tirelessly to her pedagogical mission. She was also a regular presence at the Jaca International Summer Courses, to which she contributed annually.

Once again, it is Carlos Baena who offers what is perhaps the most faithful portrait of the pianist, captured in a letter from December 1939: très calme et doucement expressif mood, in which the profound spiritual and artistic essence of the pianist is conveyed:

“This [previous piece of music] expresses wonderfully the memory I have of you—by ‘you’, I mean your entire being, everything in you that is spiritual, psychic, and physical. It resonates perfectly with me, and any attempt to express in words what Music expresses would be futile. A musical phrase can convey emotions one could never articulate in speech—especially if those feelings are of a lofty or idealistic nature” (December 1940).

Thus, Pilar Bayona—the fille aux cheveux de lin, under the evanescent spell of Debussy—conquered both salons and concert halls, earning the respect and admiration of many of her contemporaries. Through her selected correspondence, we are now invited to partake in that enduring legacy.

https://ifc.dpz.es/publicaciones/ver/id/4091

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons