- HumanitiesPhilosophy

- 27 de November de 2024

- No Comment

- 14 minutes read

Joan Cuscó: “Intellectualism represents aristocracy” (According to Serra Húnter)

Interview with Joan Cuscó i Clarasó: philosopher and hyperactive professor

Joan Cuscó: “Intellectualism represents aristocracy” (According to Serra Húnter)

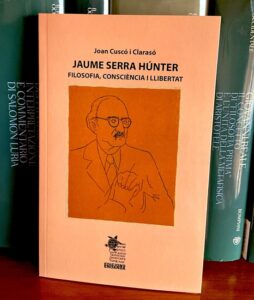

Jaume Serra Húnter is the philosopher who bridges the 19th and 20th centuries. The thinker who rehabilitates the university as a site for philosophical production, distancing it from stagnant, repetitive scholasticism. The figure who recognises the potential of Catalanism as a motor for renewal, transformation, and modernisation. This excerpt, from page 84 of Jaume Serra Húnter. Filosofía, conciencia y libertad (Enoanda), introduces the latest publication by Joan Cuscó i Clarasó, professor of Philosophy at the University of Barcelona. Joan never stops, never takes a break. He reflects with us on his trajectory.

1923. The Sociedad Catalana de Filosofía is founded. Jaume Serra Húnter is present from the outset. What did he contribute? How did it evolve?

The Sociedad Catalana de Filosofía is the outcome of a process initiated at the start of the century, aiming to create a suitable space for philosophy within Catalan culture. Among the milestones, we find the Primer Congreso Universitario Catalán (1903) and the Estudios Universitarios Catalanes (1903) in which Serra Húnter participated, alongside the Academia Catalana de la Lengua (1902), the Academia de Filosofía y Controversia Escolástica (1904), the Academia Catalana de Estudios Filosóficos (1906) and the Fundación Catalana de Filosofía (1907) among others. Of particular significance was the creation of the Instituto de Estudios Catalanes (1907) and the Seminario de Filosofía (1914), which involved Eugeni d’Ors, Josep M. Capdevila, and Joan Crexells. By 1923, all these movements and aspirations crystallised in the birth of a diverse philosophical society under the auspices of the Instituto de Estudios Catalanes and Ramon Turró. The society launched its first yearbook, developed a Catalan vocabulary, and initiated international exchanges. However, the advent of Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship abruptly interrupted its activities.

Escuela Social de la Generalitat, Escuela Normal, Ateneo Enciclopédico Popular, Ateneo Polytechnicum, Universidad Autónoma … Was there any institution where Serra Húnter did not teach?

The University of Barcelona underwent a profound philosophical transformation with the creation of the Sección de Filosofia and the arrival of figures like Tomàs Carreras Artau, Cosme Parpal, and Jaume Serra Húnter between 1912 and 1914. Their efforts bore fruit in the 1920s, with thinkers such as Joan Crexells and Joaquim Xirau, and especially during the period of the Autonomous University of Barcelona / University of Catalonia until 1938. This cannot be understood without referencing the initiatives mentioned earlier. Moreover, Serra Húnter and other university professors (including Carreras Artau and Xirau) delivered lectures, courses, and seminars in athenaeums and institutions across Catalonia. Serra Húnter spearheaded this outreach, striving to bring philosophy closer to working and popular classes.

“The growing divide between academia and broader culture is a setback”

“Our personality will be fully recognised, and nothing will stand against it when we have our own science and education” (p. 14), Serra Húnter wrote in 1931. How do you see this today?

Serra Húnter penned this during a period of political and academic euphoria. It followed years of dictatorship but also a phase—especially between 1906 and 1918—of significant progress in publishing and institutional and scientific efforts.

Today, I no longer view it with the same optimism; much has changed. Recently, the Universidad Catalana de Verano (UCE) asked me to assess the progress made in philosophy over the past two decades. While it’s undeniable that we’re far from a cultural wasteland—evidenced by the rise of publishing houses, new projects, festivals, and philosophy cafés reminiscent of those in other countries—and the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Barcelona holds a prestigious international position, the context has shifted. For Serra Húnter’s ambitions to come to fruition, we need a stronger research base and more solid foundations—elements that are currently lacking, particularly in recognizing key local contributions, such as those of Eduard Nicol. On the positive side, the number of doctoral theses on Catalan philosophers has grown, both in Catalonia and abroad. However, the growing divide between academia and broader culture is a setback—one that undermines Serra Húnter’s vision.

Philosophically, what did the Mancomunitat pass on to the Republic?

The Faculty of Arts, Philosophy, and Pedagogy achieved a significant qualitative leap in a short time because much groundwork had already been laid. The Segundo Congreso Universitario Catalán (1918) had, for instance, outlined the structure of a modern faculty: open to the world, Catalan culture, and society. The momentum generated since 1903, with Serra Húnter playing a pivotal role from the beginning, enabled the development of the Republican university. The Mancomunitat’s emphasis on science and philosophy was crucial. Subsequently, everything changed. The Tercer Congreso Universitario Catalán, planned for 1937, couldn’t take place until many decades later. The process was halted by Francoism, and most academics were exiled.

“The works of Ramon Martí d’Eixalà and Llorens i Barba were foundational to Catalan philosophy”

In 1999, you dedicated a monograph to the pioneering Francesc Xavier Llorens i Barba, who features prominently in your new book. You note that the continuity Llorens lacked was achieved by Serra. But who exactly was Llorens i Barba? Why was he important to Serra and to us?

The works of Ramon Martí d’Eixalà and Llorens i Barba were foundational to Catalan philosophy, leaving a lasting influence and reshaping the academic landscape. However, after Llorens’s death in 1872, scholasticism regained its stronghold. When Carreras i Artau and Serra Húnter looked for historical precedents to inform their own project, they turned to Llorens i Barba—not so much for his doctrines, but for his spirit, his openness, and his far-reaching vision. Llorens advocated for reconstructing philosophical thought to build a strong cultural foundation, with the university at its core. He believed in embracing all intellectual currents to find the proper course. In Madrid, the renewal was envisioned through the introduction of Krause, while in Valencia, there was a staunch defense of remaining within scholasticism. This tension continued in Serra Húnter’s work and became a defining element of Catalan university philosophy in the 20th century, though such high points have been relatively few.

Maria Carratalà (1899-1984), philosopher and musicologist like yourself. You revived her work in two of your recent books: Entre Orfeu i Plató (Enoanda, 2022) and L’Any segon de la guerra (Galerada, 2022). Who was she? Why was she forgotten, and why should we remember her?

Maria Carratalà was a woman forgotten for many years. The war and Francoism caused a rupture from which we have not yet recovered, and she was one of its victims. In fact, in 1984, she was buried in a mass grave.

Recently, we have recovered her articles written in 1938, and in the preface to that book, we explain her significant work as a member of the Lyceum Club, playwright, pianist, lecturer, and writer. She was a dynamic woman with solid philosophical and musical training. She embodies what Catalan culture was in the first third of the 20th century and the important role that women played in it. Her reflections remain very valuable, and we must read her. Her texts are collected in L’any segon de la guerra. Recull d’articles publicats a Meridià, setmanari del Front Intel·lectual Antifeixista (Galerada, 2022).

“Maria Carratalà was a woman forgotten for many years. The war and Francoism caused a rupture from which we have not yet recovered, and she was one of its victims”

In Entre Orfeu i Plató, I primarily recover her role as a thinker and music critic, which had been more hidden. In the other book, you will find her more political, philosophical side and her work as an art theorist.

Joaquim Xirau is another cental figure in your book. Who was he, really?

Joaquim Xirau is one of the “descendants” of the intellectual legacy initiated by Serra Húnter, a product of the rigorous work carried out within the university, as Xirau himself acknowledged. Although their paths diverged later, particularly on political issues, Serra Húnter and Xirau were the driving forces behind the faculty during the Second Republic. Xirau was a reformer in pedagogy and played a pivotal role in introducing Husserl’s ideas into both Catalan and Hispanic-American intellectual circles.

What is intellectualism according to Serra Húnter? Why is it anti-Orsian?

According to Serra Húnter, intellectualism represents aristocracy; it embodies the worldview of Eugeni d’Ors. It signifies a culture that does not aim to transform society from the ground up, but rather promotes an elitist, detached philosophy. Serra Húnter characterizes it as an erudite approach to knowledge—disconnected from the lived realities and their challenges—regarded as nothing more than snobbery or academic prestige, a mere professional or academic pursuit. We might call it pedantry.

It is anti-Orsian because of these very reasons and also due to the intrinsic character of “Xènius.” Moreover, Serra Húnter believed philosophy must be practiced within the university, with rigor, even if the goal is popularization—a stance he criticized in d’Ors, who didn’t publish his first substantial philosophical work until 1947.

Do you think philosophy is, as Serra Húnter said (p. 45), “(1) curiosity, (2) a form of knowledge, and (3) a moral attitude”?

Yes, philosophy is an attitude—one that shapes how we act and engage with the world. It’s a perspective that seeks constant inquiry, to avoid the rigidity of dogmatism. It is a moral attitude because knowledge must be intrinsically tied to action and life. As for whether it starts from curiosity or a conflict, that is something that warrants further discussion.

Why did Serra Húnter overlook Dalí and Salvat-Papasseit? Why wasn’t there a philosophical renewal during the 1930s?

Serra Húnter solidified his philosophical vision between 1923 and 1926. While he did develop new ideas in exile, his untimely death truncated his work. I don’t think he failed to renew himself; he was well aware of the intellectual currents of his time. However, it is true that in his treatment of art, figures like Dalí and Salvat-Papasseit are notably absent. In Dalí’s case, this omission might be attributed to timing—Dalí’s rise to prominence in Barcelona came in the mid-1920s and continued into the 1930s, when Serra was preoccupied with university organization and later, political matters. As for Salvat-Papasseit, the poet was more aligned with other figures, such as Diego Ruiz, whose political and philosophical outlooks were distant from Serra Húnter’s. However, much remains to be explored to fully grasp what Serra Húnter accomplished in the final period of his life.

“However, much remains to be explored to fully grasp what Serra Húnter accomplished in the final period of his life”

Do you think the transcendental sense that Serra Húnter gave to university teaching and science expressed in Catalan is still relevant? Are our institutions doing their part?

I believe it remains deeply relevant, yet our institutions are falling short of their responsibilities. Cultures need thought and science in their own language. This not only benefits the language itself but also the broader society. Catalan cannot be relegated solely to the domestic sphere; it must be a language of culture as well. And it can be. At present, we’re taking steps in the right direction, such as the efforts to revive analytic philosophy in Catalan. However, if Catalan scientific journals continue to lack proper recognition—partly because the government doesn’t support them—we’re headed in the wrong direction. True progress will only come through collaboration between universities, political and scientific institutions (like the IEC), and publishers. It must be a shared initiative.

Tell us what you do as a musician.

For many years, music was my livelihood. Now, I pursue it more for enjoyment, although I still research ancient instruments, working to bring them back to public life. I’ve also composed several pieces, two of which for clarinet duo will soon be presented. My work has included researching and teaching our traditional and popular music. The gralla and the clarinet are my primary instruments. I studied musicology, and this has become an integral part of my teaching at the university. Additionally, I’ve been involved for decades in the creation of the Archivo Musical de Vinseum, which preserves music spanning from the 15th to the 21st century.

What are you writing at the moment? Will you ever take a break?

At the moment, I’m working on several projects. I prefer not to go into too much detail because, as you know, progress here can be slow and sometimes comes to a halt. That said, I’m currently engaged in four books, a few of which are nearing completion. One project I can mention is my contribution to Música Politècnica (UPC), a book on music and technology, which is now in its final stages of revision.

What I do—and have always done professionally—gives me a sense of fulfillment. It’s a vocation. My work never tires me, nor do I feel the need for rest in the conventional sense. I don’t live for the weekends, nor do I dread Mondays. I’m fortunate enough to earn a living doing what I love. Of course, I do rest—but only briefly! I don’t sleep much.

Source: educational EVIDENCE

Rights: Creative Commons