- Humanities

- 19 de November de 2024

- No Comment

- 9 minutes read

Oriol Rosell: “What makes noise so fascinating is that it exists independently of us”

Interview with Oriol Rosell, Music Critic and Educator

Oriol Rosell: “What makes noise so fascinating is that it exists independently of us”

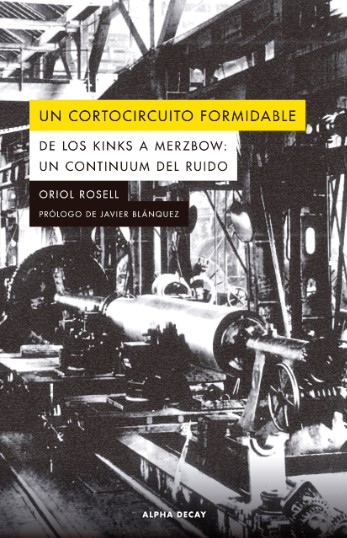

Oriol Rosell (Barcelona, 1972) surprises us with a bold and unconventional book: a history of noise and its complex relationship with music, anti-music, and anti-anti-music. Un cortocircuito formidable. De los Kinks a Maerzbow: un continuum del ruido (Alpha Decay) delves into the avant-garde aspects of subcultures over recent decades. It’s a decisive, uninhibited contribution to Cultural Studies in our context.

How did the idea for such a crazy book come about? What was the process like? Did you survive all the nihilism?

In a way, the book was already written before I began, and it wasn’t truly finished when it was published. The things that fascinate me—political thought, pop anthropology, art—are all there, and I discovered them all through music. I always stress that it’s not a book about music, but one that uses music as a starting point to delve into other realms. To me, pop—understood as the antithesis of academia—is a reflective surface where the social, cultural, and political dynamics of its time become vividly apparent. I interpret the world through pop, and that’s what I’ve tried to share. So, the process really began the moment I started discovering things beyond music, yet because of it. In this sense, the book isn’t a final statement but rather a “frozen” moment—a snapshot of my ongoing process of discovery and learning.

Is it true that you only read essays?

Yes, that’s correct. I made that choice years ago, partly for practical reasons—I simply don’t have time for everything. I decided to reserve fiction for cinema, another one of my great passions. Moreover, reading non-fiction allows me to keep learning and studying constantly. I’ve been fortunate to turn this passion into work as well; for the last four or five seasons, I’ve been hosting La Biblioteca Inflamable, a segment dedicated to essays, on the show Territori Clandestí (Ràdio 4-RNE).

Is noise “a metaphor for power, rebellion, and the rejection of norms”? Is noise “a way of knowing” (p. 13)?

It’s all that and much more. What makes noise so fascinating is that it exists independently of us. Unlike music, it’s not the product of human reflection or action. That’s why it can function as a kind of signifier without a fixed meaning—a blank symbol that we can imbue with any value we choose.

Why do you think Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music is a “mythologized” album?

Because it’s an anomaly. The aura surrounding MMM isn’t about its quality—which, in my opinion, is lacking as an avant-garde proposition—but about its context. Its symbolic weight comes from the fact that Lou Reed created it and it was released within the pop-rock market. It’s mythologized for its status as a “prank” or momentary transgression. However, I doubt it served as a gateway to other aesthetics beyond pop-rock for the New Yorker’s fans.

“For Dubuffet, in a capitalist system where art becomes an industry driven by speculation, art brut stands out as the only truly “authentic” form of art”

What is shoegaze? And art brut?

Shoegaze is a label for bands characterised by ethereal pop layered with heavy distortion. The name derives from the tendency of musicians in these bands to perform while intently focusing on their effects pedals—hence, “shoegaze,” meaning “gazing at shoes.” Art brut, on the other hand, is a term coined by Jean Dubuffet to describe art created on the marges of society, outside the influence of traditional artistic institutions, often by individuals dealing with mental health challenges. For Dubuffet, in a capitalist system where art becomes an industry driven by speculation, art brut stands out as the only truly “authentic” form of art, as it is motivated purely by creative impulses without concern for dissemination or commercialisation.

What do you think of Viennese Actionism? Would you have joined their ranks?

I think the Viennese Actionists tried to channel their anxieties and fears in a visceral and wild way. It was a reactive movement responding to specific circumstances. Today, their methods wouldn’t make sense because the aesthetics of the extreme have already been absorbed, at least within contemporary artistic practices. Besides, I’m not sure I’m young enough for that sort of thing anymore.

Is noise an “autoerotic catharsis” (p. 25)?

Undoubtedly, this is true in Japanoise. A central aspect of its discourse is the dissolution of the self within noise—the collapse of language and intellect. This has a direct connection to sexual ecstasy. The “little death” of orgasm is, at its core, a brief suspension of thought, a complete surrender to physical sensation. In Japanoise, this experience becomes deeply introspective, as the individual generates the very noise that engulfs them. It’s an almost masturbatory act.

Why is Merzbow so important?

Because, whether we like it or not, global music criticism is still shaped by Western thought. Of all Japan’s noise artists, Merzbow operates closest to European-rooted cultural ideas. Despite the harshness of his work, it’s the easiest to grasp from our perspective. Personally, I find the work of Incapacitants or Hanatarash more interesting.

You consider COUM and Throbbing Gristle to be highly pioneering. Why is that?

Because they represent the first significant and fully realized integration of avant-garde methods and concepts into the pop context. I’m fascinated by how they blend this experimental approach with a fundamentally rock-based foundation, using noise in a way that echoes “academic” art while still preserving the inherent negativity often associated with rock music.

“A crucial principle for me when writing about music is to put my personal tastes aside and focus on the analytical value of a given discourse”

Punk or Heavy Metal?

I don’t think it’s relevant. A crucial principle for me when writing about music is to put my personal tastes aside and focus on the analytical value of a given discourse. Without meaning to pat myself on the back, this is something I feel is often lacking in much of the pop literature produced in Spain. In the book, I explore many types of music that I don’t particularly enjoy but find intellectually fascinating. If I hadn’t taken this approach, I wouldn’t have written an essay; I’d have created, metaphorically speaking, a fanzine.

Bruckner or Cage?

Again, beyond my preferences, I think Cage’s contributions are far more significant. His continuous questioning of the nature of music, his reflections on listening, and the cultural frameworks that shape it are essential. If Fountain by Duchamp is considered the most important 20th-century artwork by many contemporary art experts, for me, in music, it’s Cage’s 4’33”.

What music have you been listening to lately?

You won’t believe it, but lots of vintage reggae and northern soul.

Fuente: educational EVIDENCE

Derechos: Creative Commons